Block cipher modes of operation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In cryptography, a block cipher operates on blocks of fixed length, often 64 or 128 bits. Because messages may be of any length, and because encrypting the same plaintext under the same key always produces the same output (as described in the ECB section below), several modes of operation have been invented which allow block ciphers to provide confidentiality for messages of arbitrary length.

The earliest modes described in the literature (eg, ECB, CBC, OFB and CFB) provide on

[edit] Initialization vector (IV)

All these modes (except ECB) require an initialization vector, or IV

-- a sort of 'dummy block' to kick off the process for the first real

block, and also to provide some randomization for the process. There is

no need for the IV to be secret, in most cases, but it is imp

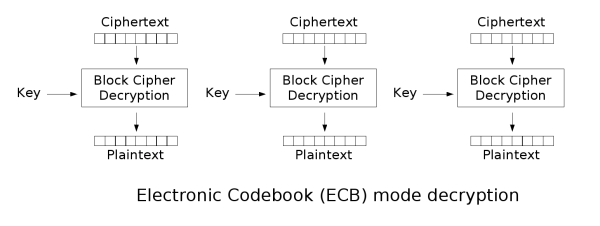

[edit] Electronic codebook (ECB)

The simplest of the encryption modes is the electronic codebook

(ECB) mode. The message is divided into blocks and each block is

encrypted separately. The disadvantage of this method is that identical

plaintext blocks are encrypted into identical ciphertext

blocks; thus, it does not hide da

Here's a striking example of the degree to which ECB can leave

plaintext da

|

|

|

| Original | Encrypted using ECB mode | Encrypted using other modes |

The image on the right is how the image might look encrypted with CBC, CTR or any of the other more secure modes—indistinguishable from random noise. Note that the random appearance of the image on the right tells us very little about whether the image has been securely encrypted; many kinds of insecure encryption have been developed which would produce output just as 'random-looking'.

ECB mode can also make protocols without integrity protection even more susceptible to replay attacks, since each block gets decrypted in exactly the same way. For example, the Phantasy Star On

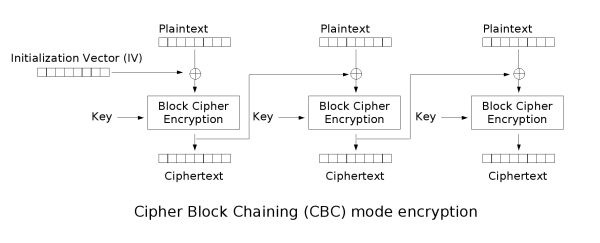

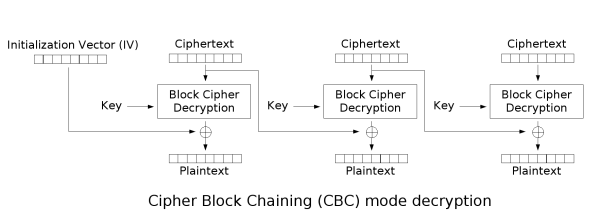

[edit] Cipher-block chaining (CBC)

CBC mode of operation was invented by IBM in 1976. [1] In the cipher-block chaining (CBC) mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted. This way, each ciphertext block is dependent on all plaintext blocks processed up to that point. Also, to make each message unique, an initialization vector must be used in the first block.

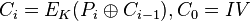

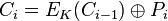

If the first block has index 1, the mathematical formula for CBC encryption is

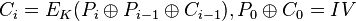

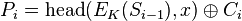

while the mathematical formula for CBC decryption is

CBC has been the most commonly used mode of operation. Its main

drawbacks are that encryption is sequential (i.e., it cannot be

parallelized), and that the message must be padded to a multiple of the

cipher block size. On

Note that a on

[edit] Propagating cipher-block chaining (PCBC)

The propagating cipher-block chaining or plaintext cipher-block chaining[2] mode was designed to cause small changes in the ciphertext to propagate indefinitely when decrypting, as well as when encrypting.

Encryption and decryption algorithms are as follows:

PCBC is used in Kerberos v4 and WASTE, most notably, but otherwise is not common. On a message encrypted in PCBC mode, if two adjacent ciphertext blocks are exchanged, this does not affect the decryption of subsequent blocks[3]. For this reason, PCBC is not used in Kerberos v5.

[edit] Cipher feedback (CFB)

The cipher feedback (CFB) mode, a close relative of CBC, makes a block cipher into a self-synchronizing stream cipher. Operation is very similar; in particular, CFB decryption is almost identical to CBC encryption performed in reverse:

This simplest way of using CFB described above is not any more

self-synchronizing than other cipher modes like CBC. If a whole

blocksize of ciphertext is lost both CBC and CFB will synchronize, but

losing on

To use CFB to make a self-synchronizing stream cipher that will synchronize for any multiple of x bits lost, start by initializing a shift register the size of the block size with the initialization vector. This is encrypted with the block cipher, and the highest x bits of the result or XOR'ed with x bits of the plaintext to produce x bits of ciphertext. These x bits of output are shifted into the shift register, and the process repeats with the next x bits of plaintext. Decryption is similar, start with the initialization vector, encrypt, and XOR the high bits of the result with x bits of the ciphertext to produce x bits of plaintext. Then shift the x bits of the ciphertext into the shift register.

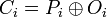

In notation, where Si is the ith state of the shift register, a << x is a shifted up x bits and head(a, x) is the x highest bits of a:

If x bits are lost from the ciphertext, the cipher will output

incorrect plaintext until the shift register on

Like CBC mode, changes in the plaintext propagate forever in the

ciphertext, and encryption cannot be parallelized. Also like CBC,

decryption can be parallelized. When decrypting, a on

CFB shares two advantages over CBC mode with the stream cipher modes

OFB and CTR: the block cipher is on

[edit] Output feedback (OFB)

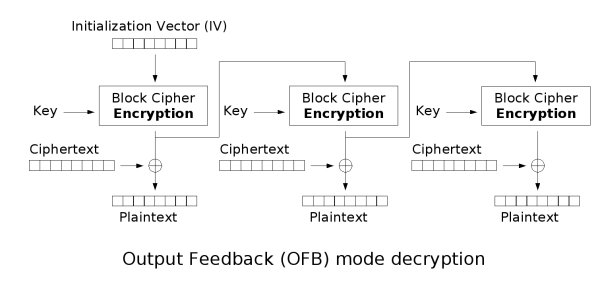

The output feedback (OFB) mode makes a block cipher into a synchronous stream cipher: it generates keystream blocks, which are then XORed with the plaintext blocks to get the ciphertext. Just as with other stream ciphers, flipping a bit in the ciphertext produces a flipped bit in the plaintext at the same location. This property allows many error correcting codes to function normally even when applied before encryption.

Because of the symmetry of the XOR operation, encryption and decryption are exactly the same:

Each output feedback block cipher operation depends on all previous

on

It is possible to obtain an OFB mode keystream by using CBC mode with a constant string of zeroes as input. This can be useful, because it allows the usage of fast hardware implementations of CBC mode for OFB mode encryption.

Using OFB mode with limited feedback like CFB mode reduces the average cycle length by a factor of 232

or more. A mathematical model proposed by Davies and Parkin and

substantiated by experimental results showed that on

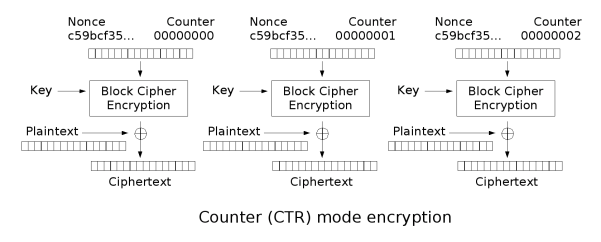

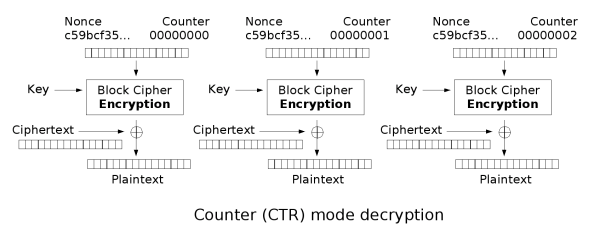

[edit] Counter (CTR)

- Note: CTR mode (CM) is also known as Integer Counter Mode (ICM) and Segmented Integer Counter (SIC) mode

Like OFB, counter mode turns a block cipher into a stream cipher. It generates the next keystream block by encrypting successive values of a "counter". The counter can be any function which produces a sequence which is guaranteed not to repeat for a long time, although an actual counter is the simplest and most popular. The usage of a simple deterministic input function raised controversial discussions, stating that "deliberately exposing a cryptosystem to a known systematic input represents an unnecessary risk."[6] By now, CTR mode is widely accepted, and problems resulting from the input function are recognized as a weakness of the underlying block cipher instead of the CTR mode. [7] Nevertheless, there are specialised attacks like a Hardware Fault Attack that is based on the usage of a simple counter function as input. [8]

CTR mode has similar characteristics to OFB, but also allows a random access property during decryption. CTR mode is well suited to operation on a multi-processor machine where blocks can be encrypted in parallel.

Note that the nonce in this graph is the same thing as the initialization vector (IV) in the other graphs. The IV/nonce and the counter can be concatenated, added, or XORed together to produce the actual unique counter block for encryption.

[edit] Integrity protection and error propagation

None of the block cipher modes of operation above provide any integrity protection

in their operation. This means that an attacker who does not know the

key may still be able to modify the da

Before the message integrity problem was widely recognized, it was

common to discuss the "error propagation" properties of a mode of

operation as a suitability criterion. It might be observed, for

example, that a on

Note in particular, that flipping bits in the IV will result in flipping the corresponding bits in the first plaintext block, with no other corruption to the decrypted message.

Some felt that such resilience was desirable in the face of random errors (eg, line noise), while others argued that it increased the scope for attackers to modify messages without assurance of detection if checked.

However, when proper integrity protection is used, such an error will result (with high probability) in the entire message being rejected. If resistance to random error is desirable, error-correcting codes should be applied to the ciphertext before transmission.

Some modes of operation have been designed to combine security and authentication. Examples of such modes are: XCBC[9], IACBC, IAPM[10], OCB, EAX, CWC, CCM, and GCM.

These authenticated encryption modes are classified as single pass

modes or double pass modes. Some modes also allow for the

authentication of unencrypted associated da

[edit] Padding

Because a block cipher works on units of a fixed size,

but messages come in a variety of lengths, some modes (mainly CBC)

require that the final block be padded before encryption. Several padding schemes exist. The simplest is to add null bytes to the plaintext

to bring its length up to a multiple of the block size, but care must

be taken that the original length of the plaintext can be recovered;

this is so, for example, if the plaintext is a C style string which contains no null bytes except at the end. Slightly more complex is the original DES method, which is to add a single on

CFB, OFB and CTR modes do not require any special measures to handle

messages whose lengths are not multiples of the block size, since they

all work by XORing the plaintext with the output of the block cipher.

The last partial block of plaintext is XORed with the first few bytes

of the last keystream

block, producing a final ciphertext block that is the same size as the

final partial plaintext block. This characteristic of stream ciphers

makes them suitable for applications that require the encrypted

ciphertext da

[edit] Other modes and other cryptographic primitives

Many more modes of operation for block ciphers have been suggested. Some of them have been accepted, fully described (even standardised), and are in use. Others have been found insecure, and should never be used. NIST maintains a list of proposed modes for AES at [1]

Disk encryption often uses special modes. Tweakable narrow-block encryption modes (LRW, XEX, and XTS) and wide-block encryption (CMC and EME) modes are designed to securely encrypt sectors of a disk. (See disk encryption theory)

Block ciphers can also be used in other cryptographic protocols. They are generally used in modes of operation similar to the block modes described here. As with all protocols, to be cryptographically secure, care must be taken to build them correctly.

There are several schemes which use a block cipher to build a cryptographic hash function. See on

Cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators (CSPRNGs) can also be built using block ciphers.

Message authentication codes (MACs) are often built from block ciphers. CBC-MAC, OMAC and PMAC are examples.

Authenticated encryption also uses block ciphers as components. It means to both encrypt and MAC at the same time. That is to both provide confidentiality and authentication. IAPM, CCM, EAX, GCM and OCB are such authenticated encryption modes.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ William F. Ehrsam, Carl H. W. Meyer, John L. Smith, Walter L. Tuchman, "Message verification and transmission error detection by block chaining", US Patent 4074066, 1976

- ^ Kaufman, C., Perlman, R., & Speciner, M (2002). Network Security. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Page 319 (2nd Ed.)

- ^ Kohl, J. "The Use of Encryption in Kerberos for Network Authentication", Proceedings, Crypto '89, 1989; published by Springer-Verlag; http://dsns.csie.nctu.edu.tw/research/crypto/HTML/PDF/C89/35.PDF

- ^ D. W. Davies and G. I. P. Parkin. The average cycle size of the key stream in output feedback encipherment. In Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of CRYPTO 82, pages 263–282, 1982

- ^ http://www.crypto.rub.de/its_seminar_ws0809.html

- ^ Robert R. Jueneman. Analysis of certain aspects of output feedback mode. In Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of CRYPTO 82, pages 99–127, 1982.

- ^ Helger Lipmaa, Phillip Rogaway, and David Wagner. Comments to NIST concerning AES modes of operation: CTR-mode encryption. 2000

- ^ R. Tirtea and G. Deconinck. Specifications overview for counter mode of operation. security aspects in case of faults. In Electrotechnical Conference, 2004. MELECON 2004. Proceedings of the 12th IEEE Mediterranean, pages 769–773 Vol.2, 2004.

- ^ Virgil D. Gligor, Pompiliu Donescu, "Fast Encryption and Authentication: XCBC Encryption and XECB Authentication Modes". Proc. Fast Software Encryption, 2001: 92-108.

- ^ Charanjit S. Jutla, "Encryption Modes with Almost Free Message Integrity", Proc. Eurocrypt 2001, LNCS 2045, May 2001.

posted on 2009-11-11 10:32 Eric Xiang 阅读(1427) 评论(0) 收藏 举报

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号