Go的并发

Go 并发模型(幻灯片) https://talks.go-zh.org/2012/concurrency.slide

go语句照常运行函数,但不会让调用者等待。

它启动了一个goroutine。

该功能类似于shell命令末尾的&。

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

func main() {

go boring("boring!") // 启动一个goroutine

}

func boring(msg string) {

for i := 0; ; i++ {

fmt.Println(msg, i)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond)

}

}

当main返回时,程序退出并将boring的函数与之一起关闭。

我们可以稍作停留,并在途中显示main和已启动的goroutine都在运行。

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

func main() {

go boring("boring!") // 启动一个goroutine,

fmt.Println("I'm listening.")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("You're boring; I'm leaving.")

}

func boring(msg string) {

for i := 0; ; i++ {

fmt.Println(msg, i)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond)

}

}

输出如下:

boring! 0

I'm listening.

boring! 1

boring! 2

boring! 3

boring! 4

boring! 5

You're boring; I'm leaving.

Goroutine

什么是goroutine?它是一个独立执行的函数,由go语句启动。

它有自己的调用堆栈,可以根据需要进行扩展和收缩。

它很轻量。有成千上万,甚至数十万的goroutine是很实际的。

这不是线程。

一个具有数千个goroutine的程序中可能只有一个线程。

相反,goroutine根据需要动态地复用到线程上,以保持所有goroutine的运行。

但如果你认为这是一条非常轻量的线程,那么你就离得不远了。

Communication

我们boring的例子作弊了:主函数看不到另一个 goroutine 的输出。

它只是打印到屏幕上,我们假装看到了对话。

真正的对话需要交流。

管道 Channels

Go 中的Channels提供了两个 goroutine 之间的连接,允许它们进行通信。

// Declaring and initializing.

var c chan int

c = make(chan int)

// or

c := make(chan int)

// Sending on a channel.

c <- 1

// Receiving from a channel.

// The "arrow" indicates the direction of data flow.

value = <-c

使用channels

通道连接主函数和boring的goroutines,以便它们可以通信。

func main() {

c := make(chan string)

go boring("boring!", c)

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Printf("You say: %q\n", <-c) // Receive expression is just a value.

}

fmt.Println("You're boring; I'm leaving.")

}

func boring(msg string, c chan string) {

for i := 0; ; i++ {

c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s %d", msg, i) // Expression to be sent can be any suitable value.

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond)

}

}

同步 Synchronization

当main函数执行<–c时,它会等待一个值被发送。

类似地,当 boring 函数执行 c <– value 时,它会等待接收器准备就绪。

发送者和接收者都必须准备好在通信中发挥自己的作用。否则我们等到他们。

因此,通道既可以通信又可以同步。

缓冲通道 An aside about buffered channels

专家注意:也可以使用缓冲区创建 Go 通道。

缓冲消除了同步。

缓冲使它们更像 Erlang 的邮箱。

缓冲通道对于某些问题可能很重要,但它们更难以推理。

不要通过共享内存来通信,而是通过通信来共享内存。

生成器: 返回一个通道的函数

通道是一级值,就像字符串或整数一样。

func main() {

c := boring("boring!") // Function returning a channel.

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Printf("You say: %q\n", <-c)

}

fmt.Println("You're boring; I'm leaving.")

}

func boring(msg string) <-chan string { // Returns receive-only channel of strings.

c := make(chan string)

go func() { // We launch the goroutine from inside the function.

for i := 0; ; i++ {

c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s %d", msg, i)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond)

}

}()

return c // Return the channel to the caller.

}

通道作为一个服务的handle

我们的boring函数返回一个通道,让我们与它提供的boring服务进行通信。

我们可以有更多的服务实例。

func main() {

joe := boring("Joe")

ann := boring("Ann")

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Println(<-joe)

fmt.Println(<-ann)

}

fmt.Println("You're both boring; I'm leaving.")

}

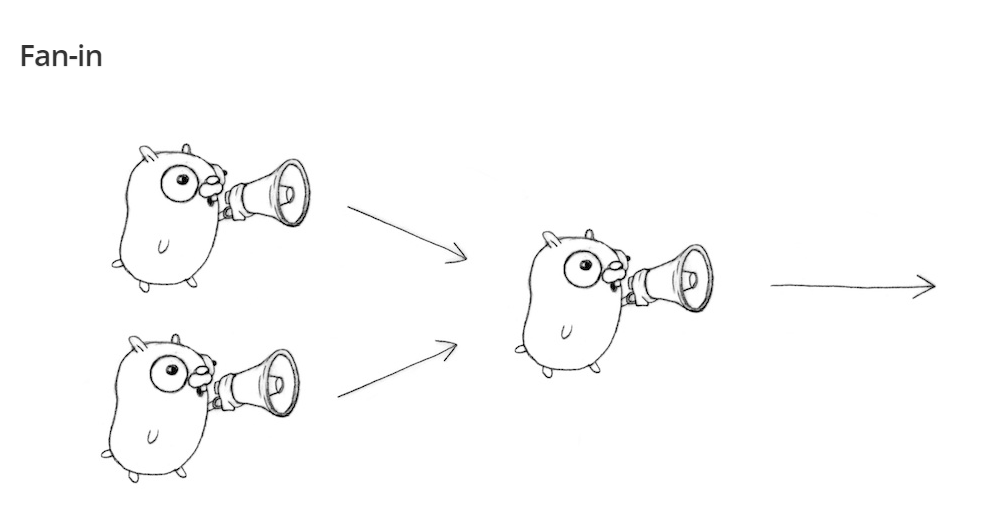

多路复用

这些程序使Joe和Ann步调一致。

相反,我们可以使用扇入(fan-in)功能,让任何准备好的人说话。

func main() {

c := fanIn(boring("Joe"), boring("Ann"))

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(<-c)

}

fmt.Println("You're both boring; I'm leaving.")

}

func fanIn(input1, input2 <-chan string) <-chan string {

c := make(chan string)

go func() { for { c <- <-input1 } }()

go func() { for { c <- <-input2 } }()

return c

}

func boring(msg string) <-chan string { // Returns receive-only channel of strings.

c := make(chan string)

go func() { // We launch the goroutine from inside the function.

for i := 0; ; i++ {

c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s %d", msg, i)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond)

}

}()

return c // Return the channel to the caller.

}

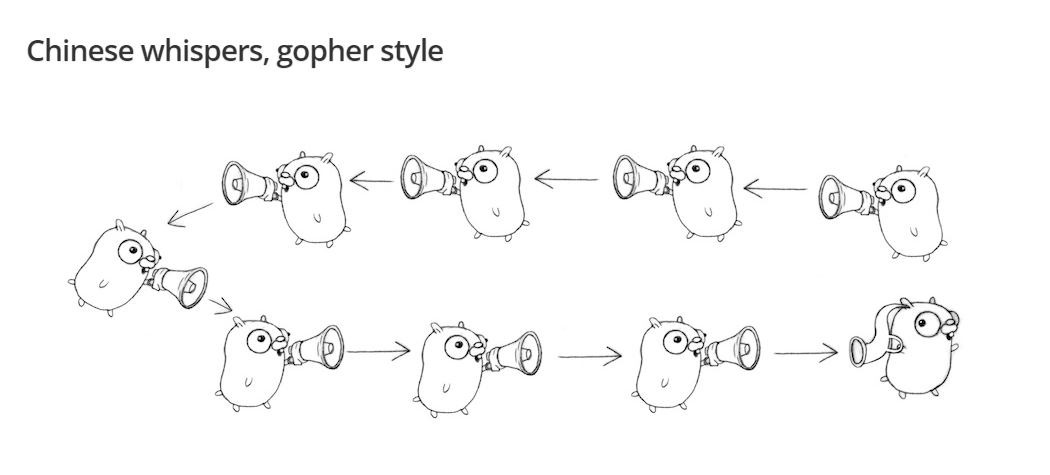

恢复排序

在通道道上发送通道,让goroutine等待轮到它。

接收所有消息,然后通过专用信道发送再次启用它们。

首先,我们定义一个消息类型,它包含一个回复通道。

每个发言者都必须等待获得批准。

func main() {

c := fanIn(boring("Joe"), boring("Ann"))

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

msg1 := <-c;fmt.Println(msg1.str)

msg2 := <-c;fmt.Println(msg2.str)

msg1.wait <- true

msg2.wait <- true

}

fmt.Println("You're both boring; I'm leaving.")

}

type Message struct {

str string

wait chan bool

}

func fanIn(input1, input2 <-chan Message) <-chan Message {

c := make(chan Message)

go func() {for {c <- <-input1}}()

go func() {for {c <- <-input2}}()

return c

}

func boring(msg string) <-chan Message {

var waitForIt = make(chan bool)

c := make(chan Message)

go func() {

for i := 0; ; i++ {

//time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(2e2)) * time.Millisecond)

c <- Message{fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", msg, i), waitForIt}

//time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(2e2)) * time.Millisecond)

<-waitForIt

}

}()

return c

}

Select

并发特有的控制结构。

select 语句提供了另一种处理多个通道的方法。

它就像一个开关,但每个案例都是一次交流:

- 所有通道都经过评估。

- 选择块,直到可以继续进行一次通信,然后继续进行。

- 如果多个可以继续,选择伪随机选择。

- 默认子句(如果存在)在没有通道准备就绪时立即执行。

select {

case v1 := <-c1:

fmt.Printf("received %v from c1\n", v1)

case v2 := <-c2:

fmt.Printf("received %v from c2\n", v1)

case c3 <- 23:

fmt.Printf("sent %v to c3\n", 23)

default:

fmt.Printf("no one was ready to communicate\n")

}

Fan-in using select

与原来的Fan-in达到同样的效果

func main() {

c := fanIn(boring("Joe"), boring("Ann"))

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

fmt.Println(<-c)

}

fmt.Println("You're both boring; I'm leaving.")

}

func fanIn(input1, input2 <-chan string) <-chan string {

c := make(chan string)

go func() {

for {

select {

case s := <-input1: c <- s

case s := <-input2: c <- s

}

}

}()

return c

}

func boring(msg string) <-chan string { // Returns receive-only channel of strings.

c := make(chan string)

go func() { // We launch the goroutine from inside the function.

for i := 0; ; i++ {

c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s %d", msg, i)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond)

}

}()

return c // Return the channel to the caller.

}

Timeout using select

time.After 函数返回阻塞指定持续时间的通道。

在间隔之后,通道传送当前时间一次

func main() {

c := boring("Joe")

for {

select {

case s := <-c:

fmt.Println(s)

case <-time.After(1 * time.Second):

fmt.Println("You're too slow.")

return

}

}

}

使用select的整个会话超时

在循环外创建一次计时器,以使整个对话超时。

(在上一个程序中,每个消息都有一个超时。)

func main() {

c := boring("Joe")

timeout := time.After(5 * time.Second)

for {

select {

case s := <-c:

fmt.Println(s)

case <-timeout:

fmt.Println("You talk too much.")

return

}

}

}

退出通道

func main() {

quit := make(chan bool)

c := boring("Joe", quit)

for i := rand.Intn(10); i >= 0; i-- {

fmt.Println(<-c)

}

quit <- true

fmt.Println("You're both boring; I'm leaving.")

}

func boring(msg string, quit chan bool) <-chan string { // Returns receive-only channel of strings.

c := make(chan string)

go func() { // We launch the goroutine from inside the function.

for i := 0; ; i++ {

select {

case c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", msg, i):

// do nothing

case <-quit:

return

}

}

}()

return c // Return the channel to the caller.

}

从退出的频道接收信息

func main() {

quit := make(chan string)

c := boring("Joe", quit)

for i := rand.Intn(10); i >= 0; i-- {

fmt.Println(<-c)

}

quit <- "Bye!"

fmt.Printf("Joe says: %q\n", <-quit)

}

func boring(msg string, quit chan string) <-chan string { // Returns receive-only channel of strings.

c := make(chan string)

go func() { // We launch the goroutine from inside the function.

for i := 0; ; i++ {

select {

case c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", msg, i):

// do nothing

case <-quit:

// cleanup()

quit <- "See you!"

return

}

}

}()

return c // Return the channel to the caller.

}

串接 Daisy-chain

func f(left, right chan int) {

left <- 1 + <-right

}

func main() {

const n = 10000

leftmost := make(chan int)

right := leftmost

left := leftmost

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

right = make(chan int)

go f(left, right)

left = right

}

go func(c chan int) { c <- 1 }(right)

fmt.Println(<-leftmost)

}

报数

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号