>>> help()

help> PRECEDENCE

Operator precedence

*******************

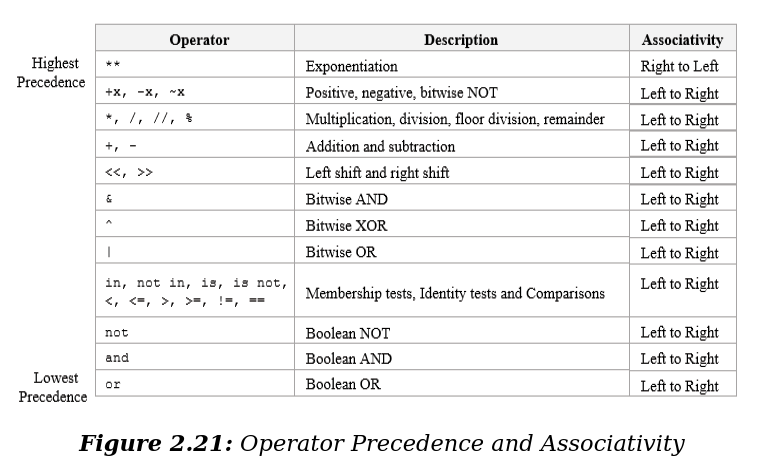

The following table summarizes the operator precedence in Python, from

highest precedence (most binding) to lowest precedence (least

binding). Operators in the same box have the same precedence. Unless

the syntax is explicitly given, operators are binary. Operators in

the same box group left to right (except for exponentiation and

conditional expressions, which group from right to left).

Note that comparisons, membership tests, and identity tests, all have

the same precedence and have a left-to-right chaining feature as

described in the Comparisons section.

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| Operator | Description |

|=================================================|=======================================|

| "(expressions...)", "[expressions...]", "{key: | Binding or parenthesized expression, |

| value...}", "{expressions...}" | list display, dictionary display, set |

| | display |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "x[index]", "x[index:index]", | Subscription, slicing, call, |

| "x(arguments...)", "x.attribute" | attribute reference |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "await x" | Await expression |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "**" | Exponentiation [5] |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "+x", "-x", "~x" | Positive, negative, bitwise NOT |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "*", "@", "/", "//", "%" | Multiplication, matrix |

| | multiplication, division, floor |

| | division, remainder [6] |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "+", "-" | Addition and subtraction |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "<<", ">>" | Shifts |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "&" | Bitwise AND |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "^" | Bitwise XOR |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "|" | Bitwise OR |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "in", "not in", "is", "is not", "<", "<=", ">", | Comparisons, including membership |

| ">=", "!=", "==" | tests and identity tests |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "not x" | Boolean NOT |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "and" | Boolean AND |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "or" | Boolean OR |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "if" – "else" | Conditional expression |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| "lambda" | Lambda expression |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

| ":=" | Assignment expression |

+-------------------------------------------------+---------------------------------------+

-[ Footnotes ]-

[1] While "abs(x%y) < abs(y)" is true mathematically, for floats it

may not be true numerically due to roundoff. For example, and

assuming a platform on which a Python float is an IEEE 754 double-

precision number, in order that "-1e-100 % 1e100" have the same

sign as "1e100", the computed result is "-1e-100 + 1e100", which

is numerically exactly equal to "1e100". The function

"math.fmod()" returns a result whose sign matches the sign of the

first argument instead, and so returns "-1e-100" in this case.

Which approach is more appropriate depends on the application.

[2] If x is very close to an exact integer multiple of y, it’s

possible for "x//y" to be one larger than "(x-x%y)//y" due to

rounding. In such cases, Python returns the latter result, in

order to preserve that "divmod(x,y)[0] * y + x % y" be very close

to "x".

[3] The Unicode standard distinguishes between *code points* (e.g.

U+0041) and *abstract characters* (e.g. “LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A”).

While most abstract characters in Unicode are only represented

using one code point, there is a number of abstract characters

that can in addition be represented using a sequence of more than

one code point. For example, the abstract character “LATIN

CAPITAL LETTER C WITH CEDILLA” can be represented as a single

*precomposed character* at code position U+00C7, or as a sequence

of a *base character* at code position U+0043 (LATIN CAPITAL

LETTER C), followed by a *combining character* at code position

U+0327 (COMBINING CEDILLA).

The comparison operators on strings compare at the level of

Unicode code points. This may be counter-intuitive to humans. For

example, ""\u00C7" == "\u0043\u0327"" is "False", even though both

strings represent the same abstract character “LATIN CAPITAL

LETTER C WITH CEDILLA”.

To compare strings at the level of abstract characters (that is,

in a way intuitive to humans), use "unicodedata.normalize()".

[4] Due to automatic garbage-collection, free lists, and the dynamic

nature of descriptors, you may notice seemingly unusual behaviour

in certain uses of the "is" operator, like those involving

comparisons between instance methods, or constants. Check their

documentation for more info.

[5] The power operator "**" binds less tightly than an arithmetic or

bitwise unary operator on its right, that is, "2**-1" is "0.5".

[6] The "%" operator is also used for string formatting; the same

precedence applies.

Related help topics: lambda, or, and, not, in, is, BOOLEAN, COMPARISON,

BITWISE, SHIFTING, BINARY, FORMATTING, POWER, UNARY, ATTRIBUTES,

SUBSCRIPTS, SLICINGS, CALLS, TUPLES, LISTS, DICTIONARIES

【推荐】国内首个AI IDE,深度理解中文开发场景,立即下载体验Trae

【推荐】编程新体验,更懂你的AI,立即体验豆包MarsCode编程助手

【推荐】抖音旗下AI助手豆包,你的智能百科全书,全免费不限次数

【推荐】轻量又高性能的 SSH 工具 IShell:AI 加持,快人一步

· 震惊!C++程序真的从main开始吗?99%的程序员都答错了

· 别再用vector<bool>了!Google高级工程师:这可能是STL最大的设计失误

· 【硬核科普】Trae如何「偷看」你的代码?零基础破解AI编程运行原理

· 单元测试从入门到精通

· 上周热点回顾(3.3-3.9)