3_5 Interpreters for Languages with Abstraction

3_5 Interpreters for Languages with Abstraction

The Calculator language provides a means of combination through nested call expressions. However, there is no way to define new operators, give names to values, or express general methods of computation. Calculator does not support abstraction in any way. As a result, it is not a particularly powerful or general programming language. We now turn to the task of defining a general programming language that supports abstraction by binding names to values and defining new operations.

Unlike the previous section, which presented a complete interpreter as Python source code, this section takes a descriptive(描述性) approach. The companion project asks you to implement the ideas presented here by building a fully functional Scheme interpreter.

3.5.1 Structure

This section describes the general structure of a Scheme interpreter. Completing that project will produce a working implementation of the interpreter described here.

An interpreter for Scheme can share much of the same structure as the Calculator interpreter. A parser(解析器) produces an expression that is interpreted by an evaluator. The evaluation function inspects the form of an expression, and for call expressions it calls a function to apply a procedure to some arguments. Much of the difference in evaluators is associated with special forms, user-defined functions, and implementing the environment model of computation.

Parsing. The scheme_reader and scheme_tokens modules from the Calculator interpreter are nearly sufficient to parse any valid Scheme expression. However, it does not yet support quotation or dotted lists. A full Scheme interpreter should be able to parse the following input expression.

>>> read_line("(car '(1 . 2))")

Pair('car', Pair(Pair('quote', Pair(Pair(1, 2), nil)), nil))

Your first task in implementing the Scheme interpreter will be to extend scheme_reader to correctly parse dotted lists and quotation.

Evaluation. Scheme is evaluated one expression at a time. A skeleton implementation of the evaluator is defined in scheme.py of the companion project. Each expression returned from scheme_read is passed to the scheme_eval function, which evaluates an expression expr in the current environment env.

The scheme_eval function evaluates the different forms of expressions in Scheme: primitives, special forms, and call expressions. The form of a combination in Scheme can be determined by inspecting its first element. Each special form has its own evaluation rule. A simplified implementation of scheme_eval appears below. Some error checking and special form handling has been removed in order to focus our discussion. A complete implementation appears in the companion project.

>>> def scheme_eval(expr, env):

"""Evaluate Scheme expression expr in environment env."""

if scheme_symbolp(expr):

return env[expr]

elif scheme_atomp(expr):

return expr

first, rest = expr.first, expr.second

if first == "lambda":

return do_lambda_form(rest, env)

elif first == "define":

do_define_form(rest, env)

return None

else:

procedure = scheme_eval(first, env)

args = rest.map(lambda operand: scheme_eval(operand, env))

return scheme_apply(procedure, args, env)

Procedure application. The final case above invokes a second process, procedure application, that is implemented by the function scheme_apply. The procedure application process in Scheme is considerably more general than the calc_apply function in Calculator. It applies two kinds of arguments: a PrimtiveProcedure or a LambdaProcedure. A PrimitiveProcedure is implemented in Python; it has an instance attribute fn that is bound to a Python function. In addition, it may or may not require access to the current environment. This Python function is called whenever the procedure is applied.

A LambdaProcedure is implemented in Scheme. It has a body attribute that is a Scheme expression, evaluated whenever the procedure is applied. To apply the procedure to a list of arguments, the body expression is evaluated in a new environment. To construct this environment, a new frame is added to the environment, in which the formal parameters of the procedure are bound to the arguments. The body is evaluated using scheme_eval.

Eval/apply recursion. The functions that implement the evaluation process, scheme_eval and scheme_apply, are mutually recursive. Evaluation requires application whenever a call expression is encountered. Application uses evaluation to evaluate operand expressions into arguments, as well as to evaluate the body of user-defined procedures. The general structure of this mutually recursive process appears in interpreters quite generally: evaluation is defined in terms of application and application is defined in terms of evaluation.

This recursive cycle ends with language primitives. Evaluation has a base case that is evaluating a primitive expression. Some special forms also constitute(构成) base cases without recursive calls. Function application has a base case that is applying a primitive procedure. This mutually recursive structure, between an eval function that processes expression forms and an apply function that processes functions and their arguments, constitutes the essence of the evaluation process.

3.5.2 Environments

Now that we have described the structure of our Scheme interpreter, we turn to implementing the Frame class that forms environments. Each Frame instance represents an environment in which symbols are bound to values. A frame has a dictionary of bindings, as well as a parent frame that is None for the global frame.

Bindings are not accessed directly, but instead through two Frame methods: lookup and define. The first implements the look-up procedure of the environment model of computation described in Chapter 1. A symbol is matched against the bindings of the current frame. If it is found, the value to which it is bound is returned. If it is not found, look-up proceeds to the parent frame. On the other hand, the define method always binds a symbol to a value in the current frame.

The implementation of lookup and the use of define are left as exercises. As an illustration of their use, consider the following example Scheme program:

(define (factorial n))

(if (= n 0) 1 (* n (factorial (- n 1))))

(factorial 5)

120

The first input expression is a define special form, evaluated by the do_define_form Python function. Defining a function has several steps:

- Check the format of the expression to ensure that it is a well-formed Scheme list with at least two elements following the keyword define.

- Analyze the first element, in this case a Pair, to find the function name factorial and formal parameter list (n).

- Create a LambdaProcedure with the supplied formal parameters, body, and parent environment.

- Bind the symbol factorial to this function, in the first frame of the current environment. In this case, the environment consists only of the global frame.

The second input is a call expression. The procedure passed to scheme_apply is the LambdaProcedure just created and bound to the symbol factorial. The args passed is a one-element Scheme list (5). To apply the procedure, a new frame is created that extends the global frame (the parent environment of the factorial procedure). In this frame, the symbol n is bound to the value 5. Then, the body of factorial is evaluated in that environment, and its value is returned.

3.5.3 Data as Programs

In thinking about a program that evaluates Scheme expressions, an analogy might be helpful. One operational view of the meaning of a program is that a program is a description of an abstract machine. For example, consider again this procedure to compute factorials:

(define (factorial n))

(if (= n 0) 1 (* n (factorial (- n 1))))

We could express an equivalent program in Python as well, using a conditional expression.

>>> def factorial(n):

return 1 if n == 1 else n * factorial(n - 1)

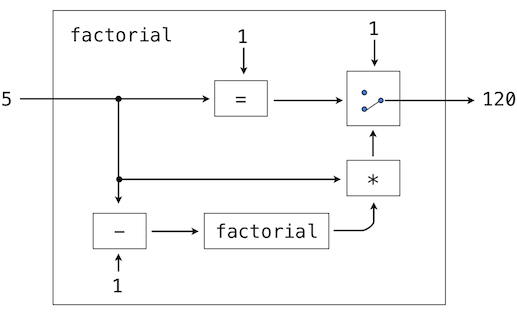

We may regard this program as the description of a machine containing parts that decrement, multiply, and test for equality, together with a two-position switch and another factorial machine. (The factorial machine is infinite because it contains another factorial machine within it.) The figure below is a flow diagram for the factorial machine, showing how the parts are wired together.

In a similar way, we can regard the Scheme interpreter as a very special machine that takes as input a description of a machine. Given this input, the interpreter configures itself to emulate the machine described. For example, if we feed our evaluator the definition of factorial the evaluator will be able to compute factorials.

From this perspective, our Scheme interpreter is seen to be a universal machine. It mimics other machines when these are described as Scheme programs. It acts as a bridge between the data objects that are manipulated by our programming language and the programming language itself. Image that a user types a Scheme expression into our running Scheme interpreter. From the perspective of the user, an input expression such as (+ 2 2) is an expression in the programming language, which the interpreter should evaluate. From the perspective of the Scheme interpreter, however, the expression is simply a sentence of words that is to be manipulated according to a well-defined set of rules.

That the user's programs are the interpreter's data need not be a source of confusion. In fact, it is sometimes convenient to ignore this distinction, and to give the user the ability to explicitly evaluate a data object as an expression. In Scheme, we use this facility whenever employing the run procedure. Similar functions exist in Python: the eval function will evaluate a Python expression and the exec function will execute a Python statement. Thus,

>>> eval('2+2')

4

and

>>> 2+2

4

both return the same result. Evaluating expressions that are constructed as a part of execution is a common and powerful feature in dynamic programming languages. In few languages is this practice as common as in Scheme, but the ability to construct and evaluate expressions during the course of execution of a program can prove to be a valuable tool for any programmer.

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号