Python is becoming the world’s most popular coding language

Python is becoming the world’s most popular coding language

But its rivals are unlikely to disappear

Jul 26th 2018

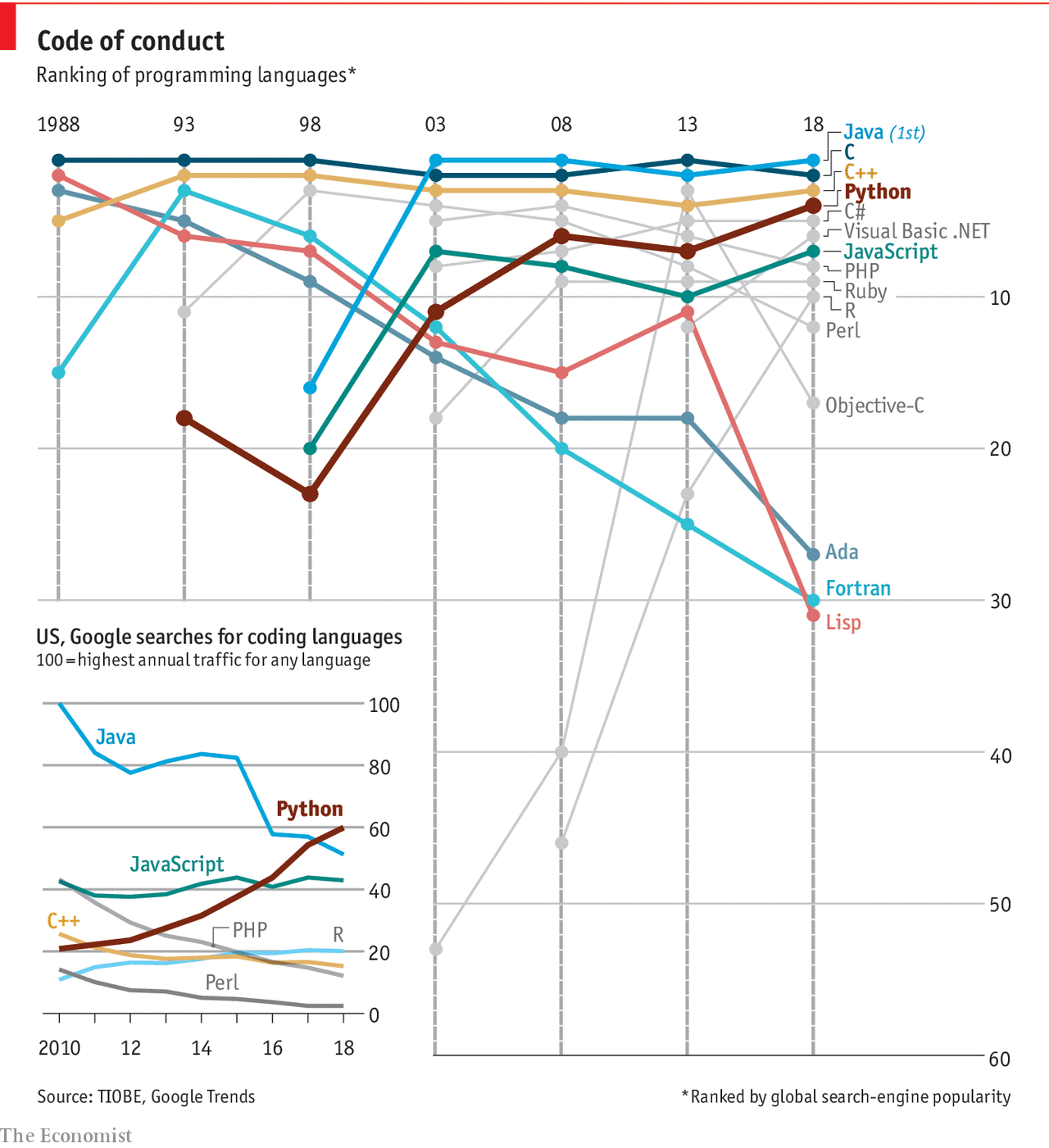

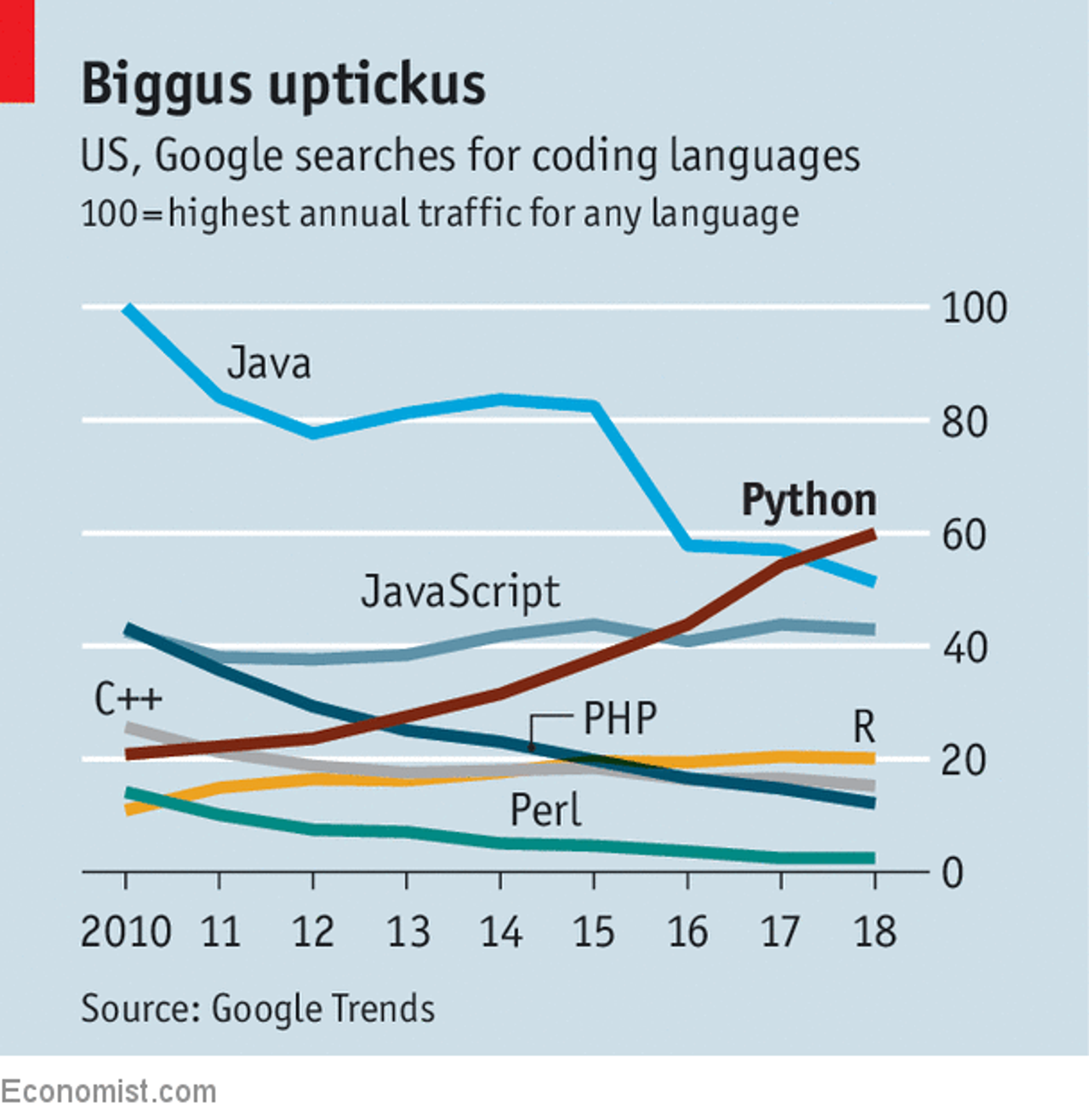

“I CERTAINLY didn’t set out to create a language that was intended for mass consumption,” says Guido van Rossum, a Dutch computer scientist who devised Python, a programming language, in 1989. But nearly three decades on, his invention has overtaken almost all of its rivals and brought coding to the fingertips of people who were once baffled by it. In the past 12 months Americans have searched for Python on Google more often than for Kim Kardashian, a reality-TV star. The number of queries has trebled since 2010, while those for other major programming languages have been flat or declining.

The language’s two main advantages are its simplicity and flexibility. Its straightforward syntax and use of indented spaces make it easy to learn, read and share. Its avid practitioners, known as Pythonistas, have uploaded 145,000 custom-built software packages to an online repository. These cover everything from game development to astronomy, and can be installed and inserted into a Python program in a matter of seconds. This versatility means that the Central Intelligence Agency has used it for hacking, Google for crawling webpages, Pixar for producing movies and Spotify for recommending songs. Some of the most popular packages harness “machine learning”, by crunching large quantities of data to pick out patterns that would otherwise be imperceptible.

With such a rapidly growing user base and wide array of capabilities, Python might seem destined to become the lingua franca of coding, rendering all other competitors obsolete. That is unlikely, according to Grady Booch, IBM’s chief software scientist, who compares programming languages to empires. Though at times a rising power might be poised for world domination, its rivals generally survive in the technical and cultural niches in which they emerged. Python will not replace C and C++, which are “lower-level options” that give the user more control over what is going on in a computer’s processor. Nor will it kill off Java, which is popular for building complicated applications, or JavaScript, which powers most web pages.

Moreover, Pythonistas who take their language’s supremacy for granted should beware. Fortran, Lisp and Ada were all highly popular in the 1980s and 1990s, according to the TIOBE index, which tracks coding practices among professional developers. Their use has plummeted, as more efficient options have become available. No empire, regardless of its might, can last forever.

Programming languages

Python has brought computer programming to a vast new audience

And its inventor has just stepped down

Science and technology

Jul 19th 2018 edition

IN DECEMBER 1989 Guido van Rossum, a Dutch computer scientist, set himself a Christmas project. Irked by shortcomings in other programming languages, he wanted to build his own. His principles were simple. First, it should be easy to read. Rather than sprawling over line-endings and being broken up by a tangle of curly braces, each chunk would be surrounded with indented white space. Second, it should let users create their own packages of special-purpose coding modules, which could then be made available to others to form the basis of new programs. Third, he wanted a “short, unique and slightly mysterious” name. He therefore called it after Monty Python, a British comedy group. The package repository became known as the Cheese Shop.

Nearly 30 years after his Christmas invention, Mr Van Rossum resembles a technological version of the Monty Python character who accidentally became the Messiah in the film “Life of Brian”. “I certainly didn’t set out to create a language that was intended for mass consumption,” he explains. But in the past 12 months Google users in America have searched for Python more often than for Kim Kardashian, a reality-TV star. The rate of queries has trebled since 2010, while inquiries after other programming languages have been flat or declining (see chart).

The language’s popularity has grown not merely among professional developers—nearly 40% of whom use it, with a further 25% wishing to do so, according to Stack Overflow, a programming forum—but also with ordinary folk. Codecademy, a website that has taught 45m novices how to use various languages, says that by far the biggest increase in demand is from those wishing to learn Python. It is thus bringing coding to the fingertips of those once baffled by the subject. Pythonistas, as aficionados are known, have helped by adding more than 145,000 packages to the Cheese Shop, covering everything from astronomy to game development.

Mr Van Rossum, though delighted by this enthusiasm for his software, has come to find the rigours of supervising it, in his role as “benevolent dictator for life”, unbearable. He fears he has become something of an idol. “I’m uncomfortable with that fame,” he says, sounding uncannily like Brian trying to drive away the crowds of disciples. “Sometimes I feel like everything I say or do is seen as a very powerful force.” On July 12th he resigned, leaving the Pythonistas to manage themselves.

Nobody expects the faddish statistician

Python is not perfect. Other languages have more processing efficiency and specialised capabilities. C and C++ are “lower-level” options which give the user more control over what is happening within a computer’s processor. Java is popular for building large, complex applications. JavaScript is the language of choice for applications accessed via a web browser. Countless others have evolved for various purposes. But Python’s killer features—simple syntax that makes its code easy to learn and share, and its huge array of third-party packages—make it a good general-purpose language. Its versatility is shown by its range of users and uses. The Central Intelligence Agency has employed it for hacking, Pixar for producing films, Google for crawling web pages and Spotify for recommending songs.

Some of the most alluring packages that Pythonistas can find in the Cheese Shop harness artificial intelligence (AI). Users can create neural networks, which mimic the connections in a brain, to pick out patterns in large quantities of data. Mr Van Rossum says that Python has become the language of choice for AI researchers, who have produced numerous packages for it.

Not all Pythonistas are so ambitious, though. Zach Sims, Codecademy’s boss, believes many visitors to his website are attempting to acquire skills that could help them in what are conventionally seen as “non-technical” jobs. Marketers, for instance, can use the language to build statistical models that measure the effectiveness of campaigns. College lecturers can check whether they are distributing grades properly. (Even journalists on The Economist, scraping the web for data, generally use programs written in Python to do so.)

For professions that have long relied on trawling through spreadsheets, Python is especially valuable. Citigroup, an American bank, has introduced a crash course in Python for its trainee analysts. A jobs website, eFinancialCareers, reports a near-fourfold increase in listings mentioning Python between the first quarters of 2015 and 2018.

The thirst for these skills is not without risk. Cesar Brea, a partner at Bain & Company, a consultancy, warns that the scariest thing in his trade is “someone who has learned a tool but doesn’t know what is going on under the hood”. Without proper oversight, a novice playing with AI libraries could reach dodgy conclusions. Bernd Ziegler, a partner at Boston Consulting Group, says that his firm reserves such analysis to members of its data team.

Rossum’s universal robot

One solution to the problem of semi-educated tinkerers is to educate them properly in the language’s arcana. Python was already the most popular introductory language at American universities in 2014, but the teaching of it is generally limited to those studying science, technology, engineering and mathematics. A more radical proposal is to catch ’em young by offering computer science to all, and in primary schools. Hadi Partovi, the boss of Code.org, a charity, notes that 40% of American schools now offer such lessons, up from 10% in 2013. Around two-thirds of 10- to 12-year-olds have an account on Code.org’s website. Perhaps unnerved by a future filled with automated jobs, 90% of American parents want their children to study computer science.

How much longer Python’s rise will continue is anybody’s guess. There have been dominant computer languages in the past that, while not exactly “one with Nineveh and Tyre”, now skulk in the background. In the 1960s, Fortran bestrode the world. As teaching languages for neophytes, both Basic and Pascal had their moments in the sun. And Mr Partovi himself plumped for JavaScript as the language for Code.org’s core syllabus, since it remains the standard choice for animating web pages.

No computing language can ever be truly general purpose. Specialisation will necessarily remain important. It is nevertheless true that, in that long-past Yuletide, Mr Van Rossum started something memorable. He isn’t the Messiah, but he was a very clever boy.

This article appeared in the Science and technology section of the print edition under the headline "And now for something completely different"

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号