SQL queries don't start with SELECT

SQL queries don't start with SELECT

Okay, obviously many SQL queries do start with SELECT (and actually this post is only about SELECT queries, not INSERTs or anything).

But! Yesterday I was working on an explanation of window functions, and I found myself googling “can you filter based on the result of a window function”. As in – can you filter the result of a window function in a WHERE or HAVING or something?

Eventually I concluded “window functions must run after WHERE and GROUP BY happen, so you can’t do it”. But this led me to a bigger question – what order do SQL queries actually run in?.

This was something that I felt like I knew intuitively (“I’ve written at least 10,000 SQL queries, some of them were really complicated! I must know this!“) but I struggled to actually articulate what the order was.

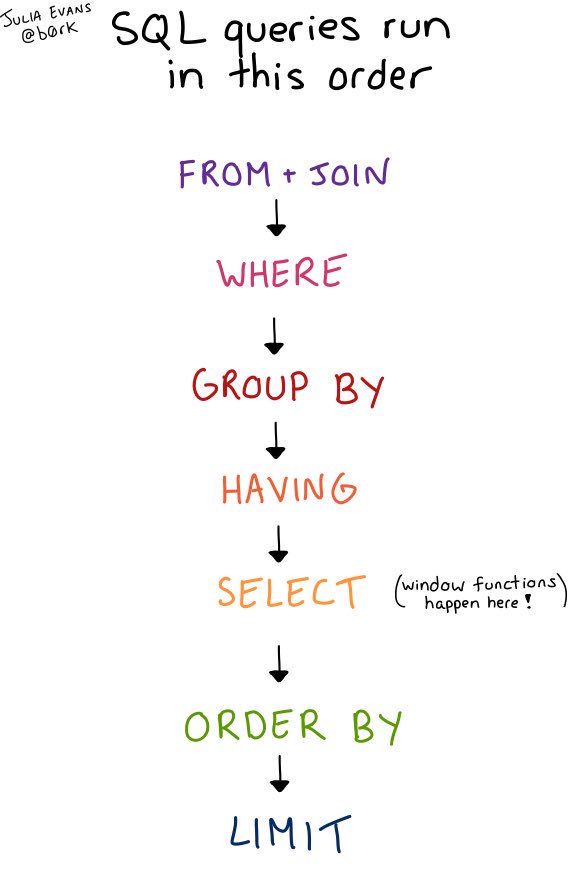

SQL queries happen in this order

I looked up the order, and here it is! (SELECT isn’t the first thing, it’s like the 5th thing!) (here it is in a tweet).

(I really want to find a more accurate way of phrasing this than “sql queries happen/run in this order” but I haven’t figured it out yet)

In a non-image format, the order is:

FROM/JOINand all theONconditionsWHEREGROUP BYHAVINGSELECT(including window functions)ORDER BYLIMIT

questions this diagram helps you answer

This diagram is about the semantics of SQL queries – it lets you reason through what a given query will return and answers questions like:

- Can I do

WHEREon something that came from aGROUP BY? (no! WHERE happens before GROUP BY!) - Can I filter based on the results of a window function? (no! window functions happen in

SELECT, which happens after bothWHEREandGROUP BY) - Can I

ORDER BYbased on something I did in GROUP BY? (yes!ORDER BYis basically the last thing, you canORDER BYbased on anything!) - When does

LIMIThappen? (at the very end!)

Database engines don’t actually literally run queries in this order because they implement a bunch of optimizations to make queries run faster – we’ll get to that a little later in the post.

So:

- you can use this diagram when you just want to understand which queries are valid and how to reason about what results of a given query will be

- you shouldn’t use this diagram to reason about query performance or anything involving indexes, that’s a much more complicated thing with a lot more variables

confounding factor: column aliases

Someone on Twitter pointed out that many SQL implementations let you use the syntax:

SELECT CONCAT(first_name, ' ', last_name) AS full_name, count(*)

FROM table

GROUP BY full_name

This query makes it look like GROUP BY happens after SELECT even though GROUP BY is first, because the GROUP BY references an alias from the SELECT. But it’s not actually necessary for the GROUP BY to run after the SELECT for this to work – the database engine can just rewrite the query as

SELECT CONCAT(first_name, ' ', last_name) AS full_name, count(*)

FROM table

GROUP BY CONCAT(first_name, ' ', last_name)

and run the GROUP BY first.

Your database engine also definitely does a bunch of checks to make sure that what you put in SELECT and GROUP BY makes sense together before it even starts to run the query, so it has to look at the query as a whole anyway before it starts to come up with an execution plan.

queries aren’t actually run in this order (optimizations!)

Database engines in practice don’t actually run queries by joining, and then filtering, and then grouping, because they implement a bunch of optimizations reorder things to make the query run faster as long as reordering things won’t change the results of the query.

One simple example of a reason why need to run queries in a different order to make them fast is that in this query:

SELECT * FROM

owners LEFT JOIN cats ON owners.id = cats.owner

WHERE cats.name = 'mr darcy'

it would be silly to do the whole left join and match up all the rows in the 2 tables if you just need to look up the 3 cats named ‘mr darcy’ – it’s way faster to do some filtering first for cats named ‘mr darcy’. And in this case filtering first doesn’t change the results of the query!

There are lots of other optimizations that database engines implement in practice that might make them run queries in a different order but there’s no room for that and honestly it’s not something I’m an expert on.

LINQ starts queries with FROM

LINQ (a querying syntax in C# and VB.NET) uses the order FROM ... WHERE ... SELECT. Here’s an example of a LINQ query:

var teenAgerStudent = from s in studentList

where s.Age > 12 && s.Age < 20

select s;

pandas (my favourite data wrangling tool) also basically works like this, though you don’t need to use this exact order – I’ll often write pandas code like this:

df = thing1.join(thing2) # like a JOIN

df = df[df.created_at > 1000] # like a WHERE

df = df.groupby('something', num_yes = ('yes', 'sum')) # like a GROUP BY

df = df[df.num_yes > 2] # like a HAVING, filtering on the result of a GROUP BY

df = df[['num_yes', 'something1', 'something']] # pick the columns I want to display, like a SELECT

df.sort_values('sometthing', ascending=True)[:30] # ORDER BY and LIMIT

df[:30]

This isn’t because pandas is imposing any specific rule on how you have to write your code, though. It’s just that it often makes sense to write code in the order JOIN / WHERE / GROUP BY / HAVING. (I’ll often put a WHERE first to improve performance though, and I think most database engines will also do a WHERE first in practice)

dplyr in R also lets you use a different syntax for querying SQL databases like Postgres, MySQL and SQLite, which is also in a more logical order.

I was really surprised that I didn’t know this

I’m writing a blog post about this because when I found out the order I was SO SURPRISED that I’d never seen it written down that way before – it explains basically everything that I knew intuitively about why some queries are allowed and others aren’t. So I wanted to write it down in the hopes that it will help other people also understand how to write SQL queries.