面向对象进阶2

__setitem__,__getitem,__delitem__

把对象属性的操作模拟成字典的操作方式,不多说,老规矩,上代码来举例说明其中的奥妙之处:

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name = name def __setitem__(self, key, value): #当对象用字典的形式设置值时触发执行 self.__dict__[key] = value #以字典的形式设置对象的值 def __getitem__(self, item): #当对象用字典的形式获取值时触发执行 return self.__dict__[item] #返回想要获取的对应的值 def __delitem__(self, key): #当对象用字典的形式删除某个值时触发执行 self.__dict__.pop(key) #删除对应的键和值

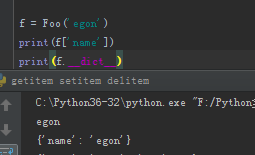

下面我们用不同的操作来验证我们的结果:

f = Foo('egon') print(f['name']) print(f.__dict__)

我们再添加一个数据属性age

f = Foo('egon') print(f['name']) print(f.__dict__) f['age'] = 18 print(f.__dict__)

我们最后实验一下删除操作:

del f['age'] print(f.__dict__)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

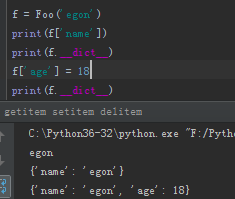

__slots__方法

1 #未使用__slots__的类 2 class People: 3 x = 1 4 def __init__(self,name): 5 self.name = name 6 #使用__slots__的类 7 class Foo: 8 __slots__=['x','y','z'] 9 def __init__(self,name): 10 self.name = name 11 12 print('这是People类的字典:%s'%People.__dict__) 13 p = People('alex') 14 print('这是p对象的字典:%s'%p.__dict__) 15 p.age = 18 16 print('这是p对象添加age属性后的字典:%s'%p.__dict__) 17 18 print('这是Foo类的字典:%s'%Foo.__dict__) 19 f = Foo('egon') 20 print('这是p对象的字典:%s'%f.__dict__) 21 f.age = 18 22 print('这是f对象添加age属性后的字典:%s'%f.__dict__)

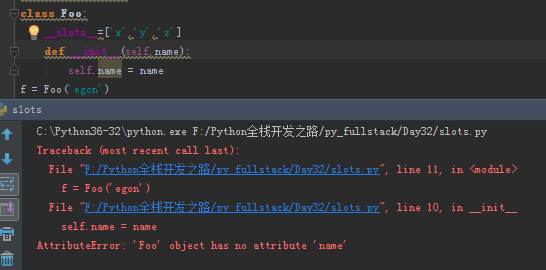

下面是结果截图,我们可以看到,我们可以看出对比,有__slots__定义属性的类实例化的时候报错了:

下面我们做下更改看看到底是怎么个用法:

class Foo: __slots__=['x','y','z'] def __init__(self,name): self.name = name f = Foo('egon')

这种初始化方式也会报错:

我再次更改:

class Foo:

__slots__=['x','y','z']

print(Foo.__dict__)

f = Foo()

print(f.__dict__)

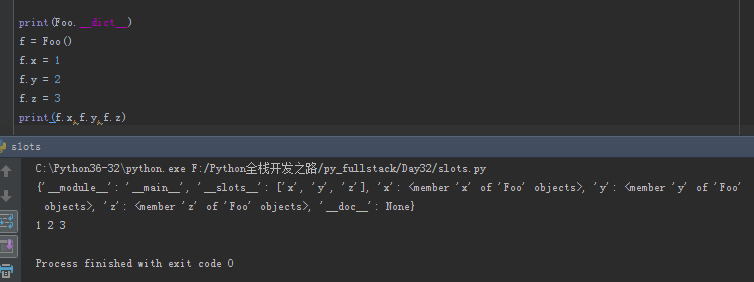

从上面的结果我们可以看出,类实例化之前是有__dict__方法来查看它字典里面的内容的,然而,在实例化之后,f中并没有了__dict__这个方法。

下面我们继续验证:

print(Foo.__dict__) f = Foo() f.x = 1 f.y = 2 f.z = 3 print(f.x,f.y,f.z)

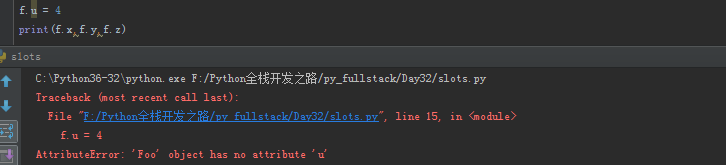

从上面结果我们可以看出实例化之后,我们可以正常使用x,y,z变量,下面我们增加属性可不可以呢?

f.u = 4

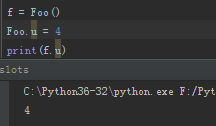

我们增加新的属性是不可行的,但这时候我们是能够通过类来直接添加属性的:

Foo.u = 4

print(f.u)

但是这种方式不建议使用,这样会打破对实例化出来的对象的限制和一致性。

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

__next__和__iter__实现迭代器协议

我们之前说过含有__iter__和__next__方法的对象就是一个迭代器,所以我们举例自己来定制一个迭代器:

1 from collections import Iterable,Iterator 2 class Foo: 3 def __init__(self,start): 4 self.start = start 5 def __iter__(self): 6 return self 7 def __next__(self): 8 if self.start>10: 9 raise StopIteration 10 n = self.start 11 self.start+=1 12 return n 13 14 f = Foo(0) 15 print(isinstance(f,Iterator)) #判断是不是一个生成器 16 print(isinstance(f,Iterable)) #判断是不是一个可迭代对象 17 for i in f: 18 print('------->',i)

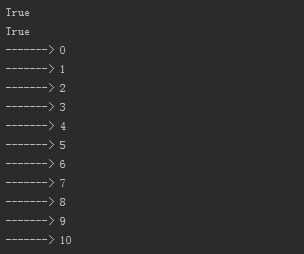

结果截图:

以上结果可以判断用__iter__和__next__方法就可以生成一个迭代器

下面我们自己来模拟一个简单功能的range函数:

1 from collections import Iterator,Iterable 2 class Range: 3 def __init__(self,start,*args): 4 self.start = start 5 self.stop = args 6 def __iter__(self): 7 return self 8 def __next__(self): 9 if self.start>=self.stop: 10 raise StopIteration 11 n = self.start 12 self.start+=1 13 return n

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

__doc__

这个方法就是查看给类或函数增加的描述信息

class Foo: '我是描述信息' pass print(Foo.__doc__)

class Foo: '我是描述信息' pass class Bar(Foo): pass print(Bar.__doc__) #该属性无法继承给子类

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

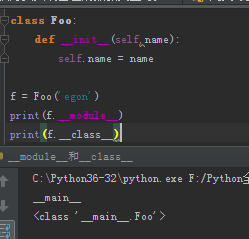

__module__和__class__

__module__ 表示当前操作的对象在那个模块

__class__ 表示当前操作的对象的类是什么

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name = name f = Foo('egon') print(f.__module__) print(f.__class__)

输出结果如下:

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

__del__

析构函数:

析构方法,当对象在内存中被释放时,自动触发执行。

注:此方法一般无须定义,因为Python是一门高级语言,程序员在使用时无需关心内存的分配和释放,因为此工作都是交给Python解释器来执行,所以,析构函数的调用是由解释器在进行垃圾回收时自动触发执行的。

1 import time 2 class Open: 3 def __init__(self,filepath,mode = 'r',encoding = 'utf-8'): 4 self.f = open(filepath,mode=mode,encoding=encoding) 5 self.filepath = filepath 6 self.mode = mode 7 self.encoding = encoding 8 def write(self,value): 9 t = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %X') 10 self.f.write('%s %s'%(t,value)) 11 def __getattr__(self, item): 12 return getattr(self.f,item) 13 def __del__(self): 14 print('__del__执行了!!') 15 self.f.close()

下面我们用各种方法来实验到底什么时候执行__del__方法:

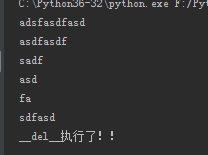

正常情况下程序都执行完成后,执行了__del__方法。

f = Open('1.txt',mode='r',encoding='utf-8') print(f.read())

输出结果:

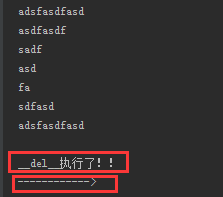

再看一种在程序为执行完的情况下:

f = Open('1.txt',mode='r',encoding='utf-8') print(f.read()) f.seek(0) print(f.readline()) del f print('------------>')

输出结果:

从这里我们可以看出,在程序未完全执行完成就执行了__del__方法,原因是我们将文件句柄f在内存中清除掉了,所以这个名字f对文件的句柄开辟的那一块内存空间没有了引用所以__del__会被触发执行,我们来进一步实验看看是不是这个原理。

f = Open('1.txt',mode='r',encoding='utf-8') print(f.read()) f.seek(0) print(f.readline()) f_bak = f del f print('------------>')

输出结果为:

由于我们在删除f之前把它的指向复制给了另一个变量f_bak,所以这时候指向文件句柄开辟的内存空间变量是两个,这时候我们删掉f,还有另一个f_bak指向那块内存空间,所以,在程序执行完成之前并没有释放掉f_bak对那块内存空间的索引,所以__del__在程序的最后才执行。

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

__enter__和__exit__

我们知道在操作文件对象的时候可以这样写:

with open(文件名) as f: '代码块'

上述叫做上下文管理协议,即with语句,为了让一个对象兼容with语句,必须在这个对象的类中声明__enter__和__exit__方法

1 import time 2 class Open: 3 def __init__(self,filepath,mode = 'r',encoding = 'utf-8'): 4 self.f = open(filepath,mode=mode,encoding=encoding) 5 self.filepath = filepath 6 self.mode = mode 7 self.encoding = encoding 8 def write(self,value): 9 t = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %X') 10 self.f.write('%s %s'%(t,value)) 11 def __getattr__(self, item): 12 return getattr(self.f,item) 13 def __enter__(self): 14 return self 15 def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): 16 self.f.close() 17 return True 18 with Open('1.txt',mode='r',encoding='utf-8') as f: 19 print(f.read())

__exit__()中的三个参数分别代表异常类型,异常值和追溯信息,with语句中代码块出现异常,则with后的代码都无法执行

1 import time 2 class Open: 3 def __init__(self,filepath,mode = 'r',encoding = 'utf-8'): 4 self.f = open(filepath,mode=mode,encoding=encoding) 5 self.filepath = filepath 6 self.mode = mode 7 self.encoding = encoding 8 def write(self,value): 9 t = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %X') 10 self.f.write('%s %s'%(t,value)) 11 def __getattr__(self, item): 12 return getattr(self.f,item) 13 def __enter__(self): 14 return self 15 def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): 16 print('执行了__exit__方法') 17 print(exc_type) 18 print(exc_val) 19 print(exc_tb) 20 with Open('1.txt',mode='r',encoding='utf-8') as f: 21 print(f.read()) 22 raise TypeError('我主动抛出了个异常看看结果') 23 f.seek(0) 24 print(f.read())

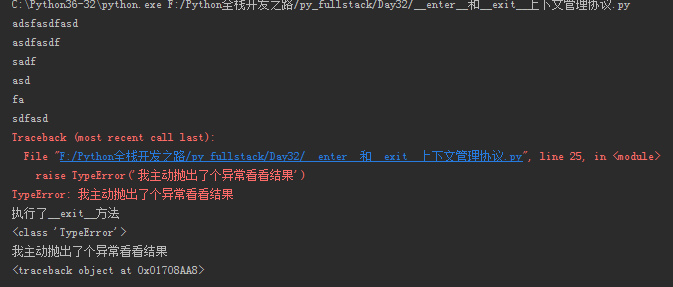

结果截图:

如果__exit__返回值为True,那么异常会被清空,就好像啥都没发生一样,with内异常后的语句无法正常执行,但是with语句以外后面的语句是正常执行的

1 import time 2 class Open: 3 def __init__(self,filepath,mode = 'r',encoding = 'utf-8'): 4 self.f = open(filepath,mode=mode,encoding=encoding) 5 self.filepath = filepath 6 self.mode = mode 7 self.encoding = encoding 8 def write(self,value): 9 t = time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %X') 10 self.f.write('%s %s'%(t,value)) 11 def __getattr__(self, item): 12 return getattr(self.f,item) 13 def __enter__(self): 14 return self 15 def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): 16 print('执行了__exit__方法') 17 print(exc_type) 18 print(exc_val) 19 print(exc_tb) 20 return True 21 with Open('1.txt',mode='r',encoding='utf-8') as f: 22 print(f.read()) 23 raise TypeError('我主动抛出了个异常看看结果') 24 f.seek(0) 25 print(f.read()) 26 print('with操作文件的语句已经结束了,这里开始新的代码块的执行!!')

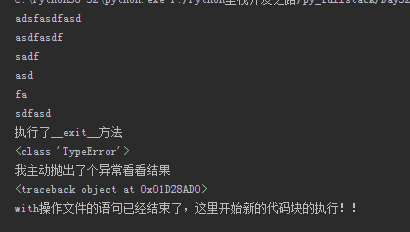

结果截图:

如果我们想正常操作一个文件,并在操作完后应该进行文件进行自动关闭的操作,我们要把代码写成第一段代码里面__exit__中的内容,将文件进行关闭操作。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

__call__

对象后面加括号,触发执行。

注:构造方法的执行是由创建对象触发的,即:对象 = 类名() ;而对于 __call__ 方法的执行是由对象后加括号触发的,即:对象() 或者 类()()

class Foo: def __init__(self): pass def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') obj = Foo() # 执行 __init__ obj() # 执行 __call__

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

元类:metaclass

平时我们创建一个类要遵守的三个要点是:

class Foo:

pass

f1=Foo() #f1是通过Foo类实例化的对象

python中一切皆是对象,类本身也是一个对象,当使用关键字class的时候,python解释器在加载class的时候就会创建一个对象(这里的对象指的是类而非类的实例)

上例可以看出f1是由Foo这个类产生的对象,而Foo本身也是对象,那它又是由哪个类产生的呢?

#type函数可以查看类型,也可以用来查看对象的类,二者是一样的 print(type(f1)) # 输出:<class '__main__.Foo'> 表示,obj 对象由Foo类创建 print(type(Foo)) # 输出:<type 'type'>

什么是元类?

元类是类的类,是类的模板

元类是用来控制如何创建类的,正如类是创建对象的模板一样

元类的实例为类,正如类的实例为对象(f1对象是Foo类的一个实例,Foo类是 type 类的一个实例)

type是python的一个内建元类,用来直接控制生成类,python中任何class定义的类其实都是type类实例化的对象

定义类有两种方式:

# 第一种方式: class People: def func(self): print('from func') # 第二种方式: def run(self): print('run') class_name = 'Foo' class_dict = { 'x' : 1, 'run':run, } bases = (object,) Foo = type(class_name,bases,class_dict)

一个类没有声明自己的元类,默认他的元类就是type,除了使用元类type,用户也可以通过继承type来自定义元类(顺便我们也可以瞅一瞅元类如何控制类的创建,工作流程是什么)

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name = name f = Foo('egon') print(type(Foo)) #输出结果:<class 'type'>

我们自定制一个元类:

1 class My_class(type): 2 def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dict): 3 print('class_name:%s'%class_name) 4 print('class_bases:',class_bases) 5 print('class_dict:%s'%class_dict) 6 print('self:%s'%self) 7 8 class Foo(metaclass=My_class): 9 x = 1 10 def __init__(self,name): 11 self.name = name 12 def run(self): 13 print('run')

上面8-10行的代码相当于做了这件事情:

Foo = type('Foo',(object,),{'x':1,'run':run})

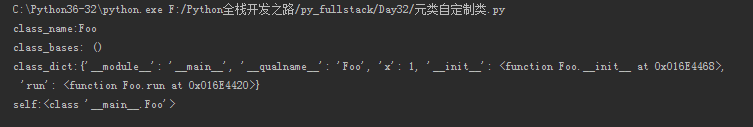

在我们执行这段代码的时候,会触发My_class中的__init__()这个方法的执行,所以执行的结果为:

我们现在将上面的代码加上一个功能,这个需求是这样的,规定每个类中的函数属性都必须加上注释,如果没加上注释说明的话就报错,代码是这样的:

1 class My_class(type): 2 def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dict): 3 for key in class_dict: 4 if not callable(class_dict[key]):continue 5 if not class_dict[key].__doc__: 6 raise TypeError('你必须加上注释!!') 7 8 class Foo(metaclass=My_class): 9 x = 1 10 def __init__(self,name): 11 self.name = name 12 def run(self): 13 print('run')

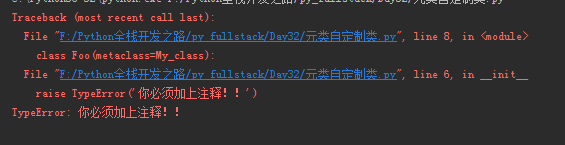

加上以上的代码后,运行程序会报错:

如果我们给每个函数方法都加上注释的话就不会出现报错的情况:

1 class My_class(type): 2 def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dict): 3 for key in class_dict: 4 if not callable(class_dict[key]):continue 5 if not class_dict[key].__doc__: 6 raise TypeError('你必须加上注释!!') 7 8 class Foo(metaclass=My_class): 9 x = 1 10 def __init__(self,name): 11 'func init' 12 self.name = name 13 def run(self): 14 'func run' 15 print('run')

元类的总结:

1 #元类总结 2 class Mymeta(type): 3 def __init__(self,name,bases,dic): 4 print('===>Mymeta.__init__') 5 6 7 def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): 8 print('===>Mymeta.__new__') 9 return type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) 10 11 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): 12 print('aaa') 13 obj=self.__new__(self) 14 self.__init__(self,*args,**kwargs) 15 return obj 16 17 class Foo(object,metaclass=Mymeta): 18 def __init__(self,name): 19 self.name=name 20 def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): 21 return object.__new__(cls) 22 23 ''' 24 需要记住一点:名字加括号的本质(即,任何name()的形式),都是先找到name的爹,然后执行:爹.__call__ 25 26 而爹.__call__一般做两件事: 27 1.调用name.__new__方法并返回一个对象 28 2.进而调用name.__init__方法对儿子name进行初始化 29 ''' 30 31 ''' 32 class 定义Foo,并指定元类为Mymeta,这就相当于要用Mymeta创建一个新的对象Foo,于是相当于执行 33 Foo=Mymeta('foo',(...),{...}) 34 因此我们可以看到,只定义class就会有如下执行效果 35 ===>Mymeta.__new__ 36 ===>Mymeta.__init__ 37 实际上class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta)是触发了Foo=Mymeta('Foo',(...),{...})操作, 38 遇到了名字加括号的形式,即Mymeta(...),于是就去找Mymeta的爹type,然后执行type.__call__(...)方法 39 于是触发Mymeta.__new__方法得到一个具体的对象,然后触发Mymeta.__init__方法对对象进行初始化 40 ''' 41 42 ''' 43 obj=Foo('egon') 44 的原理同上 45 ''' 46 47 ''' 48 总结:元类的难点在于执行顺序很绕,其实我们只需要记住两点就可以了 49 1.谁后面跟括号,就从谁的爹中找__call__方法执行 50 type->Mymeta->Foo->obj 51 Mymeta()触发type.__call__ 52 Foo()触发Mymeta.__call__ 53 obj()触发Foo.__call__ 54 2.__call__内按先后顺序依次调用儿子的__new__和__init__方法 55 '''

简单的过程分析:

1 class Mymeta(type): 2 def __init__(self,class_name,class_bases,class_dic): 3 pass 4 def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): 5 obj=self.__new__(self) #实例化一个空对象 6 self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) #相当于调用Foo中的init方法,obj.name='egon' 7 return obj #返回一个空对象 8 class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): 9 x=1 10 def __init__(self,name): 11 self.name=name #obj.name='egon' 12 def run(self): 13 'run function' 14 print('running') 15 # print(Foo.__dict__) 16 17 f=Foo('egon') #这相当于调用Mymeta中的__call__方法,并传值 18 19 print(f) 20 21 print(f.name)

“元类就是深度的魔法,99%的用户应该根本不必为此操心。如果你想搞清楚究竟是否需要用到元类,那么你就不需要它。那些实际用到元类的人都非常清楚地知道他们需要做什么,而且根本不需要解释为什么要用元类。” —— Python界的领袖 Tim Peters