linux环境编程(2): 使用pipe完成进程间通信

1. 写在前面

linux系统内核为上层应用程序提供了多种进程间通信(IPC)的手段,适用于不同的场景,有些解决进程间数据传递的问题,另一些则解决进程间的同步问题。对于同样一种IPC机制,又有不同的API供应用程序使用,目前有POSIX IPC以及System V IPC可以为应用程序提供服务。后续的系列文章将逐一介绍消息队列,共享内存,信号量,socket,fifo等进程间通信方法,本篇文章主要总结了管道相关系统调用的使用方式。文中代码可以在这个代码仓库中获取,代码中使用了我自己实现的一个单元测试框架,对测试框架感兴趣的同学可以参考上一篇文章。

2. pipe介绍

在linux环境进行日常开发时,管道是一种经常用到的进程间通信方法。在shell环境下,'|'就是连接两个进程的管道,它可以把一个进程的标准输出通过管道写到另一个进程的标准输入,利用管道以及重定向,各种命令行工具经过组合之后可以实现一个及其复杂的功能,这也是继承自UNIX的一种编程哲学。

除了在shell脚本中使用管道,另一种方式是通过系统调用去操作管道。使用pipe或者pipe2创建管道,得到两个文件描述符,分别是管道的读端和写端,有了文件描述符,进程就可以像读写普通文件一样对管道进行read和write操作,操作完成之后调用close关闭管道的两个文件描述符即可。可以看到,当完成创建之后,管道的使用和普通文件相比没有什么区别。

管道有两个特点: 1) 通常只能在有亲缘关系的进程之间进行通信; 2) 阅后即焚;有亲缘关系是指,通信的两个进程可以是父子进程或者兄弟进程,这里的父子和兄弟是一个广义的概念, 子进程可以是父进程调用了多次fork创建出来的,而不仅局限在只经过一次fork,总之,只要通信双方的进程拿到了管道的文件描述符就可以使用管道了。说”阅后即焚“是因为管道中的数据在被进程读取之后就会被管道清除掉。有一个形象的比喻说,管道就像某个进程家族各个成员之间传递情报的中转站,情报内容阅后即焚。

3. pipe的基本使用

在使用管道时,需要注意管道中数据的流动方向,通常都是把管道作为一个单向的数据通道使用的。虽然通信双方可以都持有管道的读端和写端,然后使用同一个管道实现双向通信,但这种方式实际上很少使用。下面通过几段代码说明几种使用管道的方法:

3.1 自言自语

管道虽然时进程间通信的一种手段,但一个进程自言自语也是可以的,内核并没有限制管道的两端必须由不同的进程操作。下面的代码展示了一个孤独的进程怎样通过管道自言自语,代码中使用了自己实现的测试框架cutest。执行之后它将从管道的另一头收到前一个时刻发给自己的消息。

CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, talking_to_myself) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); const char *msg = "I'm talking to myself"; write(pipefd[1], msg, strlen(msg)); char buf[32]; read(pipefd[0], buf, 32); printf("talking_to_myself: %s\n", buf); close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); }

3.2 父进程向子进程传递数据

自言自语始终是太过无聊,是时候让父子进程之间聊点什么了。因为fork之后的子进程会继承父进程的文件描述符,fork之前父进程向管道写入的数据,子进程可以在管道的另一端读到。

CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, parent2child) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); const char *msg = "parent write, child read"; write(pipefd[1], msg, strlen(msg)); if (fork() == 0) { close(pipefd[1]); char buf[64]; memset(buf, 0, 64); read(pipefd[0], buf, 64); printf("parent2child: %s\n", buf); exit(0); } close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); }

3.2 自进程向父进程传递数据

管道的方向是由通信双方操作的文件描述符决定的,子进程同样可以传递消息给父进程。

CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, child2parent) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); if (fork() == 0) { close(pipefd[0]); const char *msg = "parent read, child write"; write(pipefd[1], msg, strlen(msg)); close(pipefd[1]); exit(0); } close(pipefd[1]); char buf[64]; memset(buf, 0, 64); read(pipefd[0], buf, 64); printf("child2parent: %s\n", buf); close(pipefd[0]); }

3.3 父进程向多个子进程传递数据

当有多个子进程时,只要它们持有了管道的文件描述符,就可以利用管道通信,把父进程写进管道的数据读取出来。当然,在具体的应用中需要考虑子进程的读取顺序等因素,下面的例子只是简单的创建了多个子进程,每个进程读取一个int类型的数据,开始阶段由父进程向管道写入数据,需要说明一点,三个子进程并没有将管道内的数据都读完,当所有引用了这个管道的文件描述符都关闭了之后,内核也会在适当的时机销毁自己维护的管道。

void fork_child_read(int id, int pipefd[2], const char *msg_pregix) { if (fork() == 0) { close(pipefd[1]); int n; read(pipefd[0], &n, sizeof(int)); printf("%s: child %d get data %d\n", msg_pregix, id, n); close(pipefd[0]); exit(0); } } CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, parent2children) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) write(pipefd[1], &i, sizeof(int)); const char *msg_prefix = "parent2children:"; fork_child_read(1, pipefd, msg_prefix); fork_child_read(2, pipefd, msg_prefix); fork_child_read(3, pipefd, msg_prefix); close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); }

3.4 父进程接收多个子进程的数据

考虑这样一种场景,一个任务需要由多个子进程进行处理,最终的计算结果需要由父进程汇总,下面的代码模拟了这样的场景,代码中创建了两个子进程向管道写入数据,父进程则一直尝试读取管道内的数据。

void fork_child_write(int pipefd[2], int data) { if (fork() == 0) { close(pipefd[0]); write(pipefd[1], &data, sizeof(int)); close(pipefd[1]); exit(0); } } CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, children2parent) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); int data[] = {512, 1024}; fork_child_write(pipefd, data[0]); fork_child_write(pipefd, data[1]); close(pipefd[1]); int n; while (read(pipefd[0], &n, sizeof(int)) == sizeof(int)) { printf("children2parent: get data %d\n", n); } close(pipefd[0]); }

3.5 兄弟进程之间传递数据

如果有两个兄弟进程,进程A需要得到进程B的计算结果之后才能完成自己的任务,这时也可以用管道通信。代码中分别创建了两个进程对管道进行写和读操作,实际应用中经常还需要一种通知机制,让等待的进程知道它依赖的任务已经就绪了,这需要用到信号量,后续文章会介绍。下面代码的第二个进程在read操作时是阻塞的,会一直等到管道中数据可读,因为创建管道时没有指定O_NONBLOCK标志。

CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, two_children) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); const char *msg = "pipe between two children"; if (fork() == 0) { close(pipefd[0]); write(pipefd[1], msg, strlen(msg)); close(pipefd[1]); exit(0); } if (fork() == 0) { close(pipefd[1]); char buf[64]; memset(buf, 0, 64); read(pipefd[0], buf, 64); printf("two_children: %s\n", buf); close(pipefd[0]); exit(0); } close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); }

3.6 阻塞和非阻塞的问题

前面的例子中提到了管道的阻塞和非阻塞,这里详细说明一下这个问题。对于一个阻塞的管道,如果进程在read时,系统中存在没有关闭的写端文件描述符,但此时管道是空的,read操作就会阻塞在这里。可以这样理解,因为写端的存在,read就固执地认为在未来的某个时刻一定会有人会向管道中写入数据,所以它就阻塞在这里。对于非阻塞的管道,在前面的条件下,read会立即返回。上述的特性就要求我们在使用阻塞类型的管道时要及时关闭不使用的文件描述符,因为进程read操作时在等待的写端文件描述符很可能是由当前进程打开的,当系统中管道的其他写端都关闭了的时候,当前进程的read就会出现自己等自己的问题,类似死锁。

CUTEST_CASE(basic_pipe, blocking_read) { int pipefd[2]; pipe(pipefd); if (fork() == 0) { /* NOTE: remove the comment below if you don't want child process * blocking while reading data from pipe. Otherwise you will see that * there is still a "basic-pipe" process after you finish this test, and * you have to kill it manually.*/ // close(pipefd[1]); int num; read(pipefd[0], &num, sizeof(int)); /* NOTE: since the write end of pipe is a valid file descriptor in * current process, the print below should never execute.*/ printf("should NEVER goes here\n"); exit(0); } close(pipefd[0]); close(pipefd[1]); printf("blocking_read: parent process exit\n"); }

上述代码使用的是阻塞类型的管道,fork出的进程没有关闭管道的写端,然后执行了read操作,当父进程退出之后,系统中仍存在这个管道的写端描述符,并且就在已经处于睡眠状态下的子进程中,这种情况下将不会再有人向管道中写入数据,子进程会一直睡眠。运行代码之后使用ps命令可以看到这个睡死过去的子进程。

3.7 测试执行结果

以下是上述测试的执行结果,可以看到在程序退出之后仍然由一个"basic-pipe"进程,这是因为3.6节中的代码在子进程中没有及时关闭不使用的管道文件描述符。此时不得不手动把睡死的进程kill掉了。

[junan@arch1 test-all]$ make install [junan@arch1 test-all]$ ./script/run_test.sh basic-pipe blocking_read: parent process exit two_children: pipe between two children children2parent: get data 512 children2parent: get data 1024 parent2children:: child 1 get data 1 parent2children:: child 2 get data 2 parent2children:: child 3 get data 3 child2parent: parent read, child write talking_to_myself: I'm talking to myself cutest summary: [basic_pipe] suit result: 7/7 [basic_pipe::blocking_read] case result: Pass [basic_pipe::two_children] case result: Pass [basic_pipe::children2parent] case result: Pass [basic_pipe::parent2children] case result: Pass [basic_pipe::child2parent] case result: Pass [basic_pipe::parent2child] case result: Pass [basic_pipe::talking_to_myself] case result: Pass parent2child: parent write, child read [junan@arch1 test-all]$ ps -e|grep basic-pipe 18866 pts/2 00:00:00 basic-pipe [junan@arch1 test-all]$ kill -9 18866 [junan@arch1 test-all]$ ps -e|grep basic-pipe [junan@arch1 test-all]$

4. pipe的进阶使用

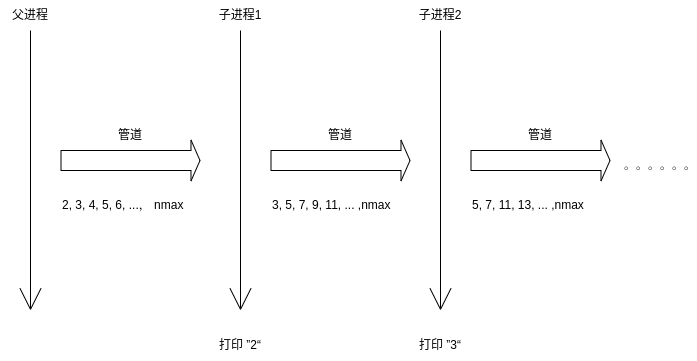

以上的几段示例代码说明了管道的一些基本使用方法和注意事项,下面看一个使用管道和多进程生成质数的问题。我们的需求是这样的,给定一个整数nmax,生成[2, nmax]区间上的所有质数,并且要求生成质数的核心逻辑使用管道和多进程。第一次碰到这个问题是在xv6操作系统的lab中,也是为了说明pipe和fork的使用。

看到这里,不妨先稍微思考一下?一个简单的想法可能是这样的,首先有一个函数,其功能是判断输入的n是否是质数,接下来遍历[2, nmax]上的整数,并且用之前的函数把质数都过滤出来,但问题是如何用管道和多进程实现这个函数的过滤功能呢?OK, 思考结束,来看看管道加多进程版本的质数生成器算法思路:

这个“质数筛子”中的每个进程主要有三个任务,1)从pipe1读取第一个数据并打印出来,并且它一定是质数;2)用得到的质数过滤pipe1中的其他数据,并把过滤出来的数据写入pipe2;3)fork自己的子进程,并把pipe2传递给它;具体的代码实现如下,当过滤之后没有数据时,就不会继续创建子进程了。

void generate_primes(int pipe1[2]) { close(pipe1[1]); int prime = 0; int err = read(pipe1[0], &prime, sizeof(int)); if (err <= 0) { close(pipe1[0]); return; } printf("%d\n", prime); int pipe2[2]; pipe(pipe2); pid_t pid = fork(); if (pid == 0) { generate_primes(pipe2); } else { int num = 0; while ((err = read(pipe1[0], &num, sizeof(int))) > 0) { if (num % prime) { write(pipe2[1], &num, sizeof(int)); } } } close(pipe1[0]); close(pipe2[0]); close(pipe2[1]); exit(0); } CUTEST_SUIT(prime_numbers_pipe) CUTEST_CASE(prime_numbers_pipe, prime_number_max30) { int nmax = 30; int pipe1[2]; pipe(pipe1); for (int i = 2; i <= nmax; ++i) write(pipe1[1], &i, sizeof(int)); if (fork() == 0) { generate_primes(pipe1); } close(pipe1[0]); close(pipe1[1]); }

代码中生成的是2到30区间上的质数,执行结果如下:

[junan@arch1 test-all]$ ./script/run_test.sh prime-number-pipe cutest summary: [prime_numbers_pipe] suit result: 1/1 [prime_numbers_pipe::prime_number_max30] case result: Pass 2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29 [junan@arch1 test-all]$

5. 写在最后

管道是一种比较基础和常用的进程间通信方法,在使用过程中需要注意及时关闭不再使用的文件描述符的问题,否则可能使得进程一直睡眠。文中的代码示例可以在我的代码仓库中找到,有兴趣的可以自己clone下来实际跑跑看。后续会继续更新其他的IPC相关的文章,并在最后使用各种IPC方法实现一个小项目,有想法的欢迎在评论区冒泡。

【推荐】国内首个AI IDE,深度理解中文开发场景,立即下载体验Trae

【推荐】编程新体验,更懂你的AI,立即体验豆包MarsCode编程助手

【推荐】抖音旗下AI助手豆包,你的智能百科全书,全免费不限次数

【推荐】轻量又高性能的 SSH 工具 IShell:AI 加持,快人一步

· TypeScript + Deepseek 打造卜卦网站:技术与玄学的结合

· 阿里巴巴 QwQ-32B真的超越了 DeepSeek R-1吗?

· 【译】Visual Studio 中新的强大生产力特性

· 10年+ .NET Coder 心语 ── 封装的思维:从隐藏、稳定开始理解其本质意义

· 【设计模式】告别冗长if-else语句:使用策略模式优化代码结构