Reading Skills

How to read quickly but effectively

In academic contexts you will have much to read, from thick text books to academic journal articles. Although this can seem overwhelming at first, you can learn to cope by using various reading skills, as well as trying to increase reading speed.

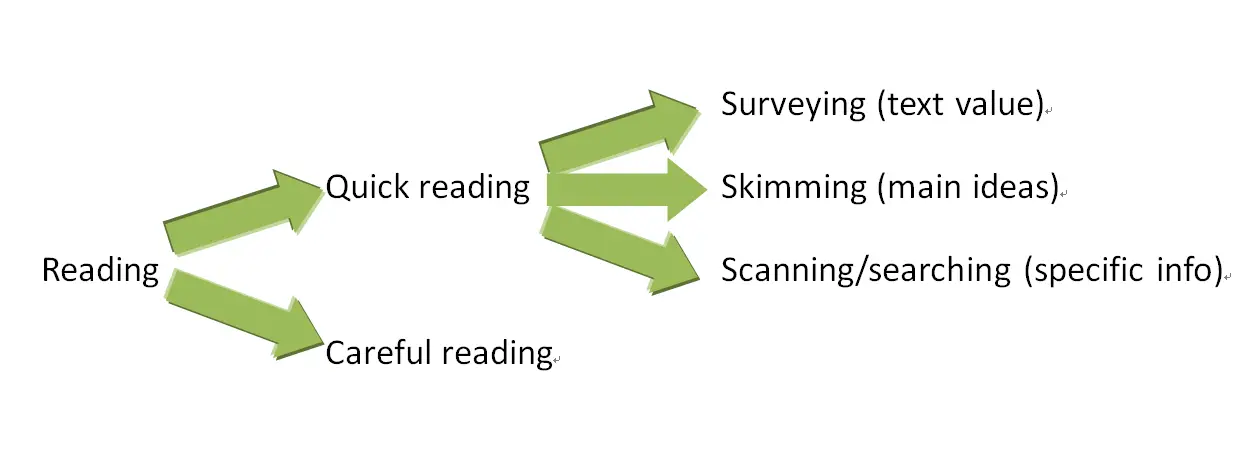

Reading skills

Often the most effective strategy for increasing reading speed is to avoid reading every word. If you just want to know whether a text is worth reading in more detail, you can survey the text by reading about the author, looking at the title, introduction, etc. If all you want to know are the main ideas, then you can skim the text, focusing on the introduction, first sentences of paragraphs, etc. Finally, if you want to find specific information you can scan or search the text for key words or phrases. Another important skill to employ is to establish a purpose before reading: knowing why you are reading will determine how you should read (e.g. skim, scan, or carefully), as well as which parts of the text may be useful (perhaps you do not need to read all). A final skill which will be important to increase speed is guessing unknown words in the text: if you stop to look up every word you do not know, you will waste a lot of time. Each of these skills is considered in more detail in the following sections.

The following diagram outlines the different approaches to reading mentioned above.

Reading speed

You cannot skim, scan or survey everything. You will still need to read texts closely for detailed understanding, often in conjunction with note-taking. The average reading speed is around 250 words per minute, and the average reader reads each word individually. It is, however, possible to recognise four or five words at a time, and the key to increasing reading speed is to take in more than one individual word when you read. A simple way to do this initially is to divide the page vertically into three or four sections, either by folding it or drawing lines, and to look only at the middle of each section. As this habit becomes more natural, you will not need to fold the page or draw lines, and may even be able to reduce the number of sections to two per page.

References

University of Leicester (n.d.) Improving your reading skills. Available at http://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/ld/resources/study/reading (Access Date 16 February, 2016).

Skimming Skills

---Get the gist

In academic contexts you will have much to read, and you will need to use various reading skills to help you read more quickly. Skimming a text is one example of such a skill (scanning and surveying a text are two others). This page explains what skimming is and what parts of the text are needed.

What is skimming?

Skimming a text means reading it quickly in order to get the main idea or gist of the text. Skimming and another quick reading skill, scanning, are often confused, though they are quite different. Skimming is concerned with finding general information, namely the main ideas, while scanning involves looking for specific information.

What parts of the text should I look at?

When you are skimming a text, you will want to focus on the parts which are more likely to contain the main ideas, while ignoring the details. These include the title, which is often a summary of the whole text. The first paragraph may also useful, as this will usually be the introduction which could contain an overview of the whole text. Likewise the final paragraph may be helpful, as it may be a conclusion and so will often contain a summary of the main points. You should also try to read the first sentence in each paragraph, as this is very often the topic sentence, and the last sentence in each paragraph, which may be a concluding sentence. Also look out for repeated words, as these may give an indication of the main points. Other aspects, such as an abstract for a technical article, or section headings, can also help. In short, you will need to focus on the following (note that not all texts contain all of these, e.g. many texts do not have abstracts or section headings).

- Title and sub-title

- Abstract

- First paragraph

- Last paragraph

- Repeated words

- Section headings

- First sentence of each paragraph

- Last sentence of each paragraph

Wallace, M.J. (2004) Study Skills in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Checklist

Below is a checklist for skimming a text. Use it to check your understanding.

| Area | OK? | Notes/comment |

| I understand what skimming is. | ||

| I know which aspects of the text are useful when skimming. | ||

| I know why these aspects are important (e.g. first sentence is often the topic sentence). |

References

Center For New Discoveries In Learning, Inc. (2016) Skimming And Scanning: Two Important Strategies For Speeding Up Your Reading. Available at http://www.howtolearn.com/2013/02/skimming-and-scanning-two-important-strategies-for-speeding-up-your-reading/ (Access Date 16 February, 2016).

McGovern, D., Matthews, M. and Mackay, S.E. (1994) Reading. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Slaght, J. and Harben, P. (2009) Reading. Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Wallace, M.J. (2004) Study Skills in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scanning

---Find info quickly

In academic contexts you will have much to read, and you will need to use various reading skills to help you read more quickly. Scanning a text is another example of such a skill (skimming and surveying a text are two others). This page explains what scanning is and how to scan a text.

What is scanning?

Scanning a text means looking through it quickly to find specific information. Scanning is commonly used in everyday life, for example when looking up a word in a dictionary or finding your friend's name in the contacts directory of your phone. Scanning and another quick reading skill, skimming, are often confused, though they are quite different. While skimming is concerned with finding general information, namely the main ideas, scanning involves looking for specific information.

How to scan a text

Before you start scanning for information, you should try to understand how the text is arranged. This will help you to locate the information more quickly. For example, when scanning for a word in a dictionary or a friend's name in your contact list, you already know that the information is arranged alphabetically. This means you can go more quickly to the part you want, without having to look through everything. For this reason, skimming can be a useful skill to use in combination with scanning, to give you a general idea of the text structure. Section headings, if there are any, can be especially useful.

When scanning, you will be looking for key words or phrases. These will be especially easy to find if they are names, because they will begin with a capital letter, or numbers/dates. Once you have decided on the area of text to scan, you should run your eyes down the page, in a zigzag pattern, to take in as much of the text as possible. This approach makes scanning seem much more random than other speed reading skills such as skimming and surveying. It is also a good idea to use your finger as you move down (or back up) the page, to focus your attention and keep track of where you are.

Searching vs. Scanning

Sometimes you may be looking for an idea rather than scanning for an actual word or phrase. In this case, you will be searching rather than scanning. Skimming the text first to help understand organisation is especially important when searching for an idea. It is also useful to guess or predict the kind of answer you will find, or some of the language associated with it. In this way, you still have words or phrases you can use to scan the text. As such, searching is part skimming, part scanning. For example, if you are reading a text on skin cancer and want to find the causes, you would skim the text to understand the structure, which might be a problem-solution structure; you might already know that exposure to sunlight is one of the causes so you might scan for 'sunlight' or 'sun', and because you are looking for causes you might scan for transition words such as 'because' or 'cause' or 'reason'.

Checklist

Below is a checklist for scanning a text. Use it to check your understanding.

| Area | OK? | Notes/comment |

| I understand what scanning is. | ||

| I know how to scan. | ||

| I know the difference between scanning and searching. |

Surveying

In academic contexts you will have much to read, and you will need to use various reading skills to help you read more quickly. Surveying a text is another example of such a skill (skimming and scanning are two others). This page explains what surveying is and what parts of the text are needed.

What is surveying?

The literal meaning of survey is to take a broad look at something, such as a piece of land, to see what the main features are or how valuable it is. Surveying a text is similar in meaning to this. It is a broad look at a text, focusing on the general aspects rather than details, with the main purpose being to decide on the value of the text, to determine whether it is worth reading more closely. If it is, then you can proceed to read in an appropriate way, such as skimming for the main points or taking notes. If it is not valuable, then discard it: there are too many texts available, and you will not have time to read them all.

What parts of the text should I look at?

As surveying looks at the general aspects of a text, it is similar to skimming, and you will need to pay attention to some of the same main features of a text, for example the title and introduction, in order to understand the gist and assess whether the text is relevant. In addition, however, you will also need to consider other aspects such as who the author is (is the writer an expert?) and when it was written (is it recent?) in order to decide if it is a credible source. These are examples of critical reading skills which are used in evaluating a text. Other aspects, such as information in graphics such as charts or diagrams, may also be useful. In short, when surveying a text, the following will be important (note that not all texts contain all of these, e.g. many texts do not have abstracts or section headings).

- Details about the author

- Date of publication

- Title and sub-title

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- Section headings

- Graphics (charts, diagrams, etc.)

Note that when surveying a text, unlike when skimming, it is not usually necessary to read the first and last lines of each paragraph, especially for longer texts. This would take too much time, and does not match the purpose - you only need a very general understanding of the main ideas in order to assess relevance.

Checklist

Below is a checklist for surveying a text. Use it to check your understanding.

| Area | OK? | Notes/comment |

| I understand what surveying is. | ||

| I know which aspects of the text are useful when surveying. | ||

| I know why these aspects are important (e.g. information on the author helps to assess credibility). |

Establishing a purpose

---Think before you read

Academic reading differs from reading for pleasure. You will often not read every word, and you are reading for a specific purpose rather than enjoyment. This page explains different types of purpose and how the purpose affects how you read, as well as suggesting a general approach to reading academic texts.

Types of purpose

Everyday reading, such as reading a novel or magazine, is usually done for pleasure. Academic reading is usually quite different from this. When reading academic texts, your general purpose is likely to be one the following:

- to get information (facts, data, etc.);

- to understand ideas or theories;

- to understand the author's viewpoint;

- to support your own views (using citations).

Many of the texts you read will have been recommended by your course tutor or will be on a reading list, and you will need to read them in order to complete assignments such as essays or reports, to take part in academic discussions, or to help you give a presentation. If you enjoy your course of study you may, of course, also get pleasure from reading these texts, but that is very definitely not your main purpose.

How the purpose affects your reading

When reading a novel you will likely always do this in the same way: from beginning to end. The same is not true of academic reading, as your purpose will affect how you read it. Exactly how you approach the reading will depend on your specific purpose. For example, if you need to list the causes of global warming in an essay you are writing, you will look for texts on the topic of global warming. You are likely to find many texts, not all of which may be suitable, so in the first instance you might survey the texts to decide which ones to read more closely. Having identified suitable texts, you will then skim through each one to find which parts, if any, mention the causes. As your task is to outline the causes, you will not need any detail and so skimming the text for the main points should be enough. In this way, you could read twenty long texts in a fairly short amount of time.

A general approach

In fact, the approach outlined above will be useful for many reading assignments you have. It is summarised in the flowchart below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Checklist

Below is a checklist for this section. Use it to check your understanding.

| Area | OK? | Notes/comment |

| I understand different types of purpose for academic reading. | ||

| I understand how the purpose affects how I read an academic text. | ||

| I am familiar with the general approach to reading academic texts. |