Python之路【第三篇】:Python基础(二)

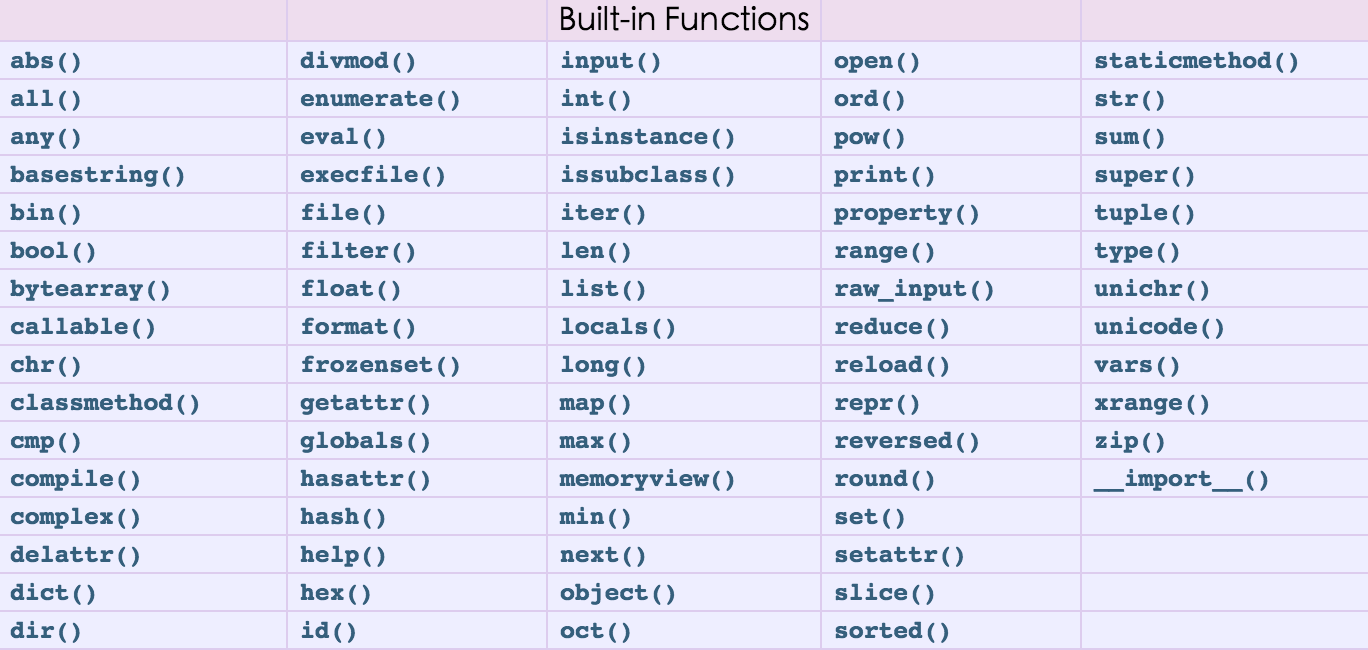

内置函数 一

详细见python文档,猛击这里

文件操作

操作文件时,一般需要经历如下步骤:

- 打开文件

- 操作文件

一、打开文件

|

1

|

文件句柄 = file('文件路径', '模式') |

注:python中打开文件有两种方式,即:open(...) 和 file(...) ,本质上前者在内部会调用后者来进行文件操作,推荐使用 open。

打开文件时,需要指定文件路径和以何等方式打开文件,打开后,即可获取该文件句柄,日后通过此文件句柄对该文件操作。

打开文件的模式有:

- r,只读模式(默认)。

- w,只写模式。【不可读;不存在则创建;存在则删除内容;】

- a,追加模式。【可读; 不存在则创建;存在则只追加内容;】

"+" 表示可以同时读写某个文件

- r+,可读写文件。【可读;可写;可追加】

- w+,写读

- a+,同a

"U"表示在读取时,可以将 \r \n \r\n自动转换成 \n (与 r 或 r+ 模式同使用)

- rU

- r+U

"b"表示处理二进制文件(如:FTP发送上传ISO镜像文件,linux可忽略,windows处理二进制文件时需标注)

- rb

- wb

- ab

二、操作操作

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

|

class file(object): def close(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 关闭文件 """ close() -> None or (perhaps) an integer. Close the file. Sets data attribute .closed to True. A closed file cannot be used for further I/O operations. close() may be called more than once without error. Some kinds of file objects (for example, opened by popen()) may return an exit status upon closing. """ def fileno(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 文件描述符 """ fileno() -> integer "file descriptor". This is needed for lower-level file interfaces, such os.read(). """ return 0 def flush(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 刷新文件内部缓冲区 """ flush() -> None. Flush the internal I/O buffer. """ pass def isatty(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 判断文件是否是同意tty设备 """ isatty() -> true or false. True if the file is connected to a tty device. """ return False def next(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 获取下一行数据,不存在,则报错 """ x.next() -> the next value, or raise StopIteration """ pass def read(self, size=None): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 读取指定字节数据 """ read([size]) -> read at most size bytes, returned as a string. If the size argument is negative or omitted, read until EOF is reached. Notice that when in non-blocking mode, less data than what was requested may be returned, even if no size parameter was given. """ pass def readinto(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 读取到缓冲区,不要用,将被遗弃 """ readinto() -> Undocumented. Don't use this; it may go away. """ pass def readline(self, size=None): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 仅读取一行数据 """ readline([size]) -> next line from the file, as a string. Retain newline. A non-negative size argument limits the maximum number of bytes to return (an incomplete line may be returned then). Return an empty string at EOF. """ pass def readlines(self, size=None): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 读取所有数据,并根据换行保存值列表 """ readlines([size]) -> list of strings, each a line from the file. Call readline() repeatedly and return a list of the lines so read. The optional size argument, if given, is an approximate bound on the total number of bytes in the lines returned. """ return [] def seek(self, offset, whence=None): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 指定文件中指针位置 """ seek(offset[, whence]) -> None. Move to new file position. Argument offset is a byte count. Optional argument whence defaults to 0 (offset from start of file, offset should be >= 0); other values are 1 (move relative to current position, positive or negative), and 2 (move relative to end of file, usually negative, although many platforms allow seeking beyond the end of a file). If the file is opened in text mode, only offsets returned by tell() are legal. Use of other offsets causes undefined behavior. Note that not all file objects are seekable. """ pass def tell(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 获取当前指针位置 """ tell() -> current file position, an integer (may be a long integer). """ pass def truncate(self, size=None): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 截断数据,仅保留指定之前数据 """ truncate([size]) -> None. Truncate the file to at most size bytes. Size defaults to the current file position, as returned by tell(). """ pass def write(self, p_str): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 写内容 """ write(str) -> None. Write string str to file. Note that due to buffering, flush() or close() may be needed before the file on disk reflects the data written. """ pass def writelines(self, sequence_of_strings): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 将一个字符串列表写入文件 """ writelines(sequence_of_strings) -> None. Write the strings to the file. Note that newlines are not added. The sequence can be any iterable object producing strings. This is equivalent to calling write() for each string. """ pass def xreadlines(self): # real signature unknown; restored from __doc__ 可用于逐行读取文件,非全部 """ xreadlines() -> returns self. For backward compatibility. File objects now include the performance optimizations previously implemented in the xreadlines module. """ pass |

三、with

为了避免打开文件后忘记关闭,可以通过管理上下文,即:

|

1

2

3

|

with open('log','r') as f: ... |

如此方式,当with代码块执行完毕时,内部会自动关闭并释放文件资源。

在Python 2.7 后,with又支持同时对多个文件的上下文进行管理,即:

|

1

2

|

with open('log1') as obj1, open('log2') as obj2: pass |

四、那么问题来了...

1、如何在线上环境优雅的修改配置文件?

原配置文件

原配置文件 需求

需求 demo

demo2、文件处理中xreadlines的内部是如何实现的呢?

自定义函数

一、背景

在学习函数之前,一直遵循:面向过程编程,即:根据业务逻辑从上到下实现功能,其往往用一长段代码来实现指定功能,开发过程中最常见的操作就是粘贴复制,也就是将之前实现的代码块复制到现需功能处,如下

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

while True: if cpu利用率 > 90%: #发送邮件提醒 连接邮箱服务器 发送邮件 关闭连接 if 硬盘使用空间 > 90%: #发送邮件提醒 连接邮箱服务器 发送邮件 关闭连接 if 内存占用 > 80%: #发送邮件提醒 连接邮箱服务器 发送邮件 关闭连接 |

腚眼一看上述代码,if条件语句下的内容可以被提取出来公用,如下:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

|

def 发送邮件(内容) #发送邮件提醒 连接邮箱服务器 发送邮件 关闭连接 while True: if cpu利用率 > 90%: 发送邮件('CPU报警') if 硬盘使用空间 > 90%: 发送邮件('硬盘报警') if 内存占用 > 80%: |

对于上述的两种实现方式,第二次必然比第一次的重用性和可读性要好,其实这就是函数式编程和面向过程编程的区别:

- 函数式:将某功能代码封装到函数中,日后便无需重复编写,仅调用函数即可

- 面向对象:对函数进行分类和封装,让开发“更快更好更强...”

函数式编程最重要的是增强代码的重用性和可读性

二、 函数的定义和使用

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

def 函数名(参数): ... 函数体 ... |

函数的定义主要有如下要点:

- def:表示函数的关键字

- 函数名:函数的名称,日后根据函数名调用函数

- 函数体:函数中进行一系列的逻辑计算,如:发送邮件、计算出 [11,22,38,888,2]中的最大数等...

- 参数:为函数体提供数据

- 返回值:当函数执行完毕后,可以给调用者返回数据。

以上要点中,比较重要有参数和返回值:

1、返回值

函数是一个功能块,该功能到底执行成功与否,需要通过返回值来告知调用者。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

def 发送短信(): 发送短信的代码... if 发送成功: return True else: return Falsewhile True: # 每次执行发送短信函数,都会将返回值自动赋值给result # 之后,可以根据result来写日志,或重发等操作 result = 发送短信() if result == False: 记录日志,短信发送失败... |

2、参数

为什么要有参数?

上例,无参数实现

上例,无参数实现 上列,有参数实现

上列,有参数实现函数的有三中不同的参数:

- 普通参数

- 默认参数

- 动态参数

普通参数

普通参数 默认参数

默认参数 动态参数一

动态参数一 动态参数二

动态参数二 动态参数三

动态参数三扩展:发送邮件实例

lambda表达式

学习条件运算时,对于简单的 if else 语句,可以使用三元运算来表示,即:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

# 普通条件语句if 1 == 1: name = 'wupeiqi'else: name = 'alex' # 三元运算name = 'wupeiqi' if 1 == 1 else 'alex' |

对于简单的函数,也存在一种简便的表示方式,即:lambda表达式

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

|

# ###################### 普通函数 ####################### 定义函数(普通方式)def func(arg): return arg + 1 # 执行函数result = func(123) # ###################### lambda ###################### # 定义函数(lambda表达式)my_lambda = lambda arg : arg + 1 # 执行函数result = my_lambda(123) |

lambda存在意义就是对简单函数的简洁表示

内置函数 二

一、map

遍历序列,对序列中每个元素进行操作,最终获取新的序列。

每个元素增加100

每个元素增加100 两个列表对应元素相加

两个列表对应元素相加二、filter

对于序列中的元素进行筛选,最终获取符合条件的序列

获取列表中大于12的所有元素集合

获取列表中大于12的所有元素集合三、reduce

对于序列内所有元素进行累计操作

获取序列所有元素的和

获取序列所有元素的和yield生成器

1、对比range 和 xrange 的区别

|

1

2

3

4

|

>>> print range(10)[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]>>> print xrange(10)xrange(10) |

如上代码所示,range会在内存中创建所有指定的数字,而xrange不会立即创建,只有在迭代循环时,才去创建每个数组。

自定义生成器nrange

自定义生成器nrange2、文件操作的 read 和 xreadlinex 的的区别

|

1

2

|

read会读取所有内容到内存xreadlines则只有在循环迭代时才获取 |

基于next自定义生成器NReadlines

基于next自定义生成器NReadlines 基于seek和tell自定义生成器NReadlines

基于seek和tell自定义生成器NReadlines装饰器

装饰器是函数,只不过该函数可以具有特殊的含义,装饰器用来装饰函数或类,使用装饰器可以在函数执行前和执行后添加相应操作。

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

def wrapper(func): def result(): print 'before' func() print 'after' return result@wrapperdef foo(): print 'foo' |

View Code

View Code View Code

View Code冒泡算法

需求:请按照从小到大对列表 [13, 22, 6, 99, 11] 进行排序

思路:相邻两个值进行比较,将较大的值放在右侧,依次比较!

第一步

第一步 第二步

第二步 第三步

第三步递归

利用函数编写如下数列:

斐波那契数列指的是这样一个数列 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233,377,610,987,1597,2584,4181,6765,10946,17711,28657,46368