深度学习中Embedding层有什么用?

这篇博客翻译自国外的深度学习系列文章的第四篇,想查看其他文章请点击下面的链接,人工翻译也是劳动,如果你觉得有用请打赏,转载请打赏:

- Setting up AWS & Image Recognition

- Convolutional Neural Networks

- More on CNNs & Handling Overfitting

在深度学习实验中经常会遇Eembedding层,然而网络上的介绍可谓是相当含糊。比如 Keras中文文档中对嵌入层 Embedding的介绍除了一句 “嵌入层将正整数(下标)转换为具有固定大小的向量”之外就不愿做过多的解释。那么我们为什么要使用嵌入层 Embedding呢? 主要有这两大原因:

-

使用One-hot 方法编码的向量会很高维也很稀疏。假设我们在做自然语言处理(NLP)中遇到了一个包含2000个词的字典,当时用One-hot编码时,每一个词会被一个包含2000个整数的向量来表示,其中1999个数字是0,要是我的字典再大一点的话这种方法的计算效率岂不是大打折扣?

-

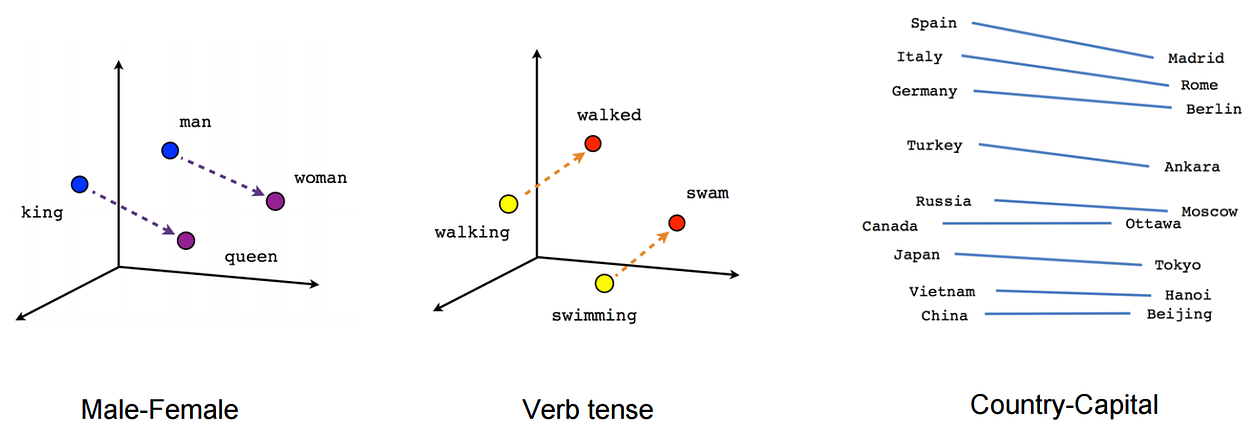

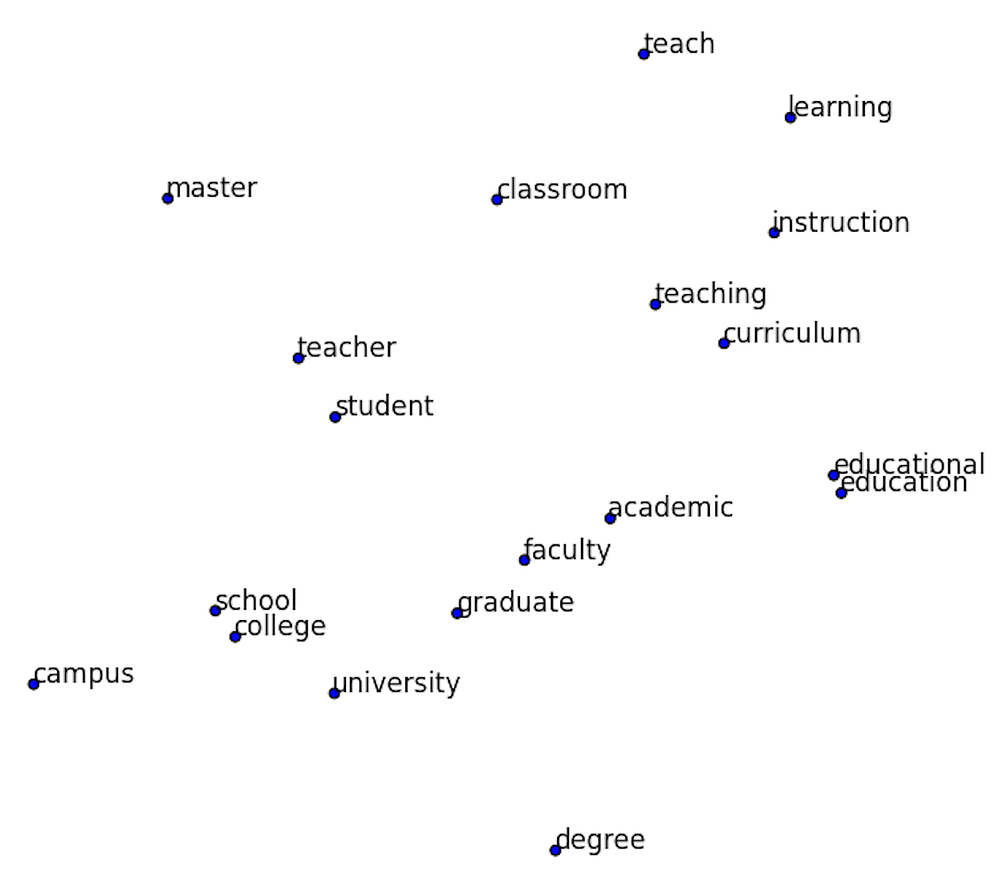

训练神经网络的过程中,每个嵌入的向量都会得到更新。如果你看到了博客上面的图片你就会发现在多维空间中词与词之间有多少相似性,这使我们能可视化的了解词语之间的关系,不仅仅是词语,任何能通过嵌入层 Embedding 转换成向量的内容都可以这样做。

上面说的概念可能还有点含糊. 那我们就举个栗子看看嵌入层 Embedding 对下面的句子做了什么:)。Embedding的概念来自于word embeddings,如果您有兴趣阅读更多内容,可以查询 word2vec 。

“deep learning is very deep”

使用嵌入层embedding 的第一步是通过索引对该句子进行编码,这里我们给每一个不同的句子分配一个索引,上面的句子就会变成这样:

1 2 3 4 1

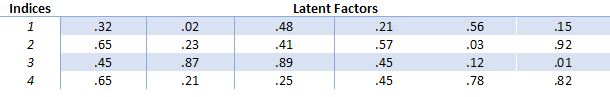

接下来会创建嵌入矩阵,我们要决定每一个索引需要分配多少个‘潜在因子’,这大体上意味着我们想要多长的向量,通常使用的情况是长度分配为32和50。在这篇博客中,为了保持文章可读性这里为每个索引指定6个潜在因子。嵌入矩阵就会变成这样:

这样,我们就可以使用嵌入矩阵来而不是庞大的one-hot编码向量来保持每个向量更小。简而言之,嵌入层embedding在这里做的就是把单词“deep”用向量[.32, .02, .48, .21, .56, .15]来表达。然而并不是每一个单词都会被一个向量来代替,而是被替换为用于查找嵌入矩阵中向量的索引。其次这种方法面对大数据时也可有效计算。由于在深度神经网络的训练过程中嵌入向量也会被更新,我们就可以探索在高维空间中哪些词语之间具有彼此相似性,再通过使用t-SNE 这样的降维技术就可以将这些相似性可视化。

Not Just Word Embeddings

These previous examples showed that word embeddings are very important in the world of Natural Language Processing. They allow us to capture relationships in language that are very difficult to capture otherwise. However, embedding layers can be used to embed many more things than just words. In my current research project I am using embedding layers to embed online user behavior. In this case I am assigning indices to user behavior like ‘page view on page type X on portal Y’ or ‘scrolled X pixels’. These indices are then used for constructing a sequence of user behavior.

In a comparison of ‘traditional’ machine learning models (SVM, Random Forest, Gradient Boosted Trees) with deep learning models (deep neural networks, recurrent neural networks) I found that this embedding approach worked very well for deep neural networks.

The ‘traditional’ machine learning models rely on a tabular input that is feature engineered. This means that we, as researchers, decide what gets turned into a feature. In these cases features could be: amount of homepages visited, amount of searches done, total amount of pixels scrolled. However, it is very difficult to capture the spatial (time) dimension when doing feature-engineering. By using deep learning and embedding layers we can efficiently capture this spatial dimension by supplying a sequence of user behavior (as indices) as input for the model.

In my research the Recurrent Neural Network with Gated Recurrent Unit/Long-Short Term Memory performed best. The results were very close. From the ‘traditional’ feature engineered models Gradient Boosted Trees performed best. I will write a blog post about this research in more detail in the future. I think my next blog post will explore Recurrent Neural Networks in more detail.

Other research has explored the use of embedding layers to encode student behavior in MOOCs (Piech et al., 2016) and users’ path through an online fashion store (Tamhane et al., 2017).

Recommender Systems

Embedding layers can even be used to deal with the sparse matrix problem in recommender systems. Since the deep learning course (fast.ai) uses recommender systems to introduce embedding layers I want to explore them here as well.

Recommender systems are being used everywhere and you are probably being influenced by them every day. The most common examples are Amazon’s product recommendation and Netflix’s program recommendation systems. Netflix actually held a $1,000,000 challenge to find the best collaborative filtering algorithm for their recommender system. You can see a visualization of one of these models here.

There are two main types of recommender systems and it is important to distinguish between the two.

- Content-based filtering. This type of filtering is based on data about the item/product. For example, we have our users fill out a survey on what movies they like. If they say that they like sci-fi movies we recommend them sci-fi movies. In this case al lot of meta-information has to be available for all items.

- Collaborative filtering: Let’s find other people like you, see what they liked and assume you like the same things. People like you = people who rated movies that you watched in a similar way. In a large dataset this has proven to work a lot better than the meta-data approach. Essentially asking people about their behavior is less good compared to looking at their actual behavior. Discussing this further is something for the psychologists among us.

In order to solve this problem we can create a huge matrix of the ratings of all users against all movies. However, in many cases this will create an extremely sparse matrix. Just think of your Netflix account. What percentage of their total supply of series and movies have you watched? It’s probably a pretty small percentage. Then, through gradient descent we can train a neural network to predict how high each user would rate each movie. Let me know if you would like to know more about the use of deep learning in recommender systems and we can explore it further together. In conclusion, embedding layers are amazing and should not be overlooked.

If you liked this posts be sure to recommend it so others can see it. You can also follow this profile to keep up with my process in the Fast AI course. See you there!

References

Piech, C., Bassen, J., Huang, J., Ganguli, S., Sahami, M., Guibas, L. J., & Sohl-Dickstein, J. (2015). Deep knowledge tracing. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 505–513).

Tamhane, A., Arora, S., & Warrier, D. (2017, May). Modeling Contextual Changes in User Behaviour in Fashion e-Commerce. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 539–550). Springer, Cham.

Embedding layers in keras

嵌入层embedding用在网络的开始层将你的输入转换成向量,所以当使用 Embedding前应首先判断你的数据是否有必要转换成向量。如果你有categorical数据或者数据仅仅包含整数(像一个字典一样具有固定的数量)你可以尝试下Embedding 层。

如果你的数据是多维的你可以对每个输入共享嵌入层或尝试单独的嵌入层。

from keras.layers.embeddings import Embedding

Embedding(input_dim, output_dim, embeddings_initializer='uniform', embeddings_regularizer=None, activity_regularizer=None, embeddings_constraint=None, mask_zero=False, input_length=None)- 1

- 2

- 3

-The first value of the Embedding constructor is the range of values in the input. In the example it’s 2 because we give a binary vector as input.

- The second value is the target dimension.

- The third is the length of the vectors we give.

- input_dim: int >= 0. Size of the vocabulary, ie. 1+maximum integer

index occuring in the input data.

本文译自:https://medium.com/towards-data-science/deep-learning-4-embedding-layers-f9a02d55ac12

How does embedding work? An example demonstrates best what is going on.

Assume you have a sparse vector [0,1,0,1,1,0,0] of dimension seven. You can turn it into a non-sparse 2d vector like so:

model = Sequential()

model.add(Embedding(2, 2, input_length=7))

model.compile('rmsprop', 'mse')

model.predict(np.array([[0,1,0,1,1,0,0]]))- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

array([[[ 0.03005414, -0.02224021],

[ 0.03396987, -0.00576888],

[ 0.03005414, -0.02224021],

[ 0.03396987, -0.00576888],

[ 0.03396987, -0.00576888],

[ 0.03005414, -0.02224021],

[ 0.03005414, -0.02224021]]], dtype=float32)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Where do these numbers come from? It’s a simple map from the given range to a 2d space:

model.layers[0].W.get_value()- 1

array([[ 0.03005414, -0.02224021],

[ 0.03396987, -0.00576888]], dtype=float32)- 1

- 2

The 0-value is mapped to the first index and the 1-value to the second as can be seen by comparing the two arrays. The first value of the Embedding constructor is the range of values in the input. In the example it’s 2 because we give a binary vector as input. The second value is the target dimension. The third is the length of the vectors we give.

So, there is nothing magical in this, merely a mapping from integers to floats.

Now back to our ‘shining’ detection. The training data looks like a sequences of bits:

X- 1

array([[ 0., 1., 1., 1., 0., 1., 0., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 0., 0., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 0.,

0., 0., 1., 0., 1., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 0., 0., 0.,

0., 1., 0., 1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 0., 1., 0., 1., 0., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1.]])- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

If you want to use the embedding it means that the output of the embedding layer will have dimension (5, 19, 10). This works well with LSTM or GRU (see below) but if you want a binary classifier you need to flatten this to (5, 19*10):

model = Sequential()

model.add(Embedding(3, 10, input_length= X.shape[1] ))

model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid'))

model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='rmsprop')

model.fit(X, y=y, batch_size=200, nb_epoch=700, verbose=0, validation_split=0.2, show_accuracy=True, shuffle=True)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

It detects ‘shining’ flawlessly:

model.predict(X)- 1

array([[ 1.00000000e+00],

[ 8.39483363e-08],

[ 9.71878720e-08],

[ 7.35597965e-08],

[ 9.91844118e-01]], dtype=float32)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An LSTM layer has historical memory and so the dimension outputted by the embedding works in this case, no need to flatten things:

model = Sequential()

model.add(Embedding(vocab_size, 10))

model.add(LSTM(5))

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid'))

model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='rmsprop')

model.fit(X, y=y, nb_epoch=500, verbose=0, validation_split=0.2, show_accuracy=True, shuffle=True)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Obviously, it predicts things as well:

model.predict(X)- 1

array([[ 0.96855599],

[ 0.01917232],

[ 0.01917362],

[ 0.01917258],

[ 0.02341695]], dtype=float32)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

本文译自:http://www.orbifold.net/default/2017/01/10/embedding-and-tokenizer-in-keras/

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号