OI 生涯回忆录

[前言]

自从 NOI 2021 退役,已经淡出算法竞赛两年有余, 突然想写一篇回忆录, 纪念那段激情燃烧的岁月....

[小学]

与众多竞赛生不同,小学时的我并不是在老师和同学们的赞许和鼓励中长大的。那时的我没有展现出过人的天赋,相反,我在班级里是一个不折不扣的异类。也许是 "开窍" 比别人晚的缘故吧,一直到二年级,我仍不会上楼梯; 体育课上跑步测试,我永远是倒数第一; 就连简单的广播体操,我也怎么学都不会做。

更加不幸的是,我还碰上了一位人品极其低劣的班主任。 她不仅从未给予我任何帮助,还总是责怪我拖班级后腿,并对我冷嘲热讽。记得有一次,一名同学在他的一篇作文里,以一种描绘小丑的口吻,写出了大量我闹的 "笑话",其中还包括我因为害怕被嘲笑,不敢上体育课的 "丑态"。我的班主任竟当着全班的面,将他的那篇作文读了出来,完全不顾及我的感受。她每读一段,班里便发出阵阵笑声。那时,好似所有人都喜欢将快乐建立在我的痛苦之上。

童年时期过早接触人性之恶,使我拥有了与他人截然不同的性格。由于痛恨集体主义,直到高中,我都很少参加春游,秋游,甚至是毕业典礼之类的集体活动。与此同时,我也变得极其争强好胜。在后来的日子里,正是因极度渴望证明自己,使我最终走上了竞赛的道路。

五年级时, 由于体育课和美术课没能拿到 "优", 我开始为择校而发愁。 当年,想要进入市里较好的民办初中, 必须要所有科目都拿到 "优"。 否则,就只能上一所很普通的公办学校。而在江苏,一所公办初中只有不到 50% 的人能上高中。

我的父母并没有很 “硬" 的关系, 能让我 "走后门" 进入民办初中。

怎么办?唯一的办法是,在编程 / 奥数比赛中取得较好的成绩,被破格录取。我最终选择了重点学习编程。而做出此决定的原因,是由于我在一年级时自学了打字,使我自认为对计算机很擅长。

与其他城市不同,常州市有着一套极其完善的信息学培养体系,使得许多成绩优异的同学很早便有了接触编程的机会。而我进入培训班时,是五年级下半学期,记得那时部分同龄人已经学习了两年有余。可想而知,我和他们的差距是巨大的。刚开始的几节课,我听得云里雾里。 由于没有热爱,我的学习态度也十分糟糕。有时题目不会做,我便偷偷打开同学给我的小游戏,开始自娱自乐。

不料,由于在高级班时的一次课堂测试中意外取得了领先,我对编程从此产生了浓厚的兴趣,在班里的成绩也越来越突出。第二年秋天,我已成为了培训班里最优秀的学生。随后,我又通过自学深度优先搜索 (DFS), 宽度优先搜索 (BFS) 和二分查找等基础算法连跳了三个班,并因优异的成绩在何静老师的推荐下,进入江苏省常州高级中学,在那里接受了更加正规、专业的编程训练。

记得那时每晚做完作业,我都会打开电脑练习编程,那是我第一次为了一个目标而努力奋斗。当然,因为热爱,我也享受着这个过程。

六年级第二学期举行的市编程比赛, 我顺利从 300 多名选手中脱颖而出, 获得大市第一, 提前四个月就被常州外国语学校录取。当时,很多人看到成绩,都感到很惊诧。 他们没有想到,一个从没听说过名字的人, 获得了最高分。

随后四个月无忧无虑的生活, 让我明白了一个非常深刻的道理 : 想要远离那些自己厌恶的人和事,获得真正的自由,必须自己足够强大。

灰暗的小学时光终于结束了,新的生活也从此开始。

升初中的那个暑假里,我第一次去参加省里组织的信息学集训 (地点在镇江扬中)。 教练觉得初中组的题可能对我太简单,于是让我去高中组感受一下。第一次考试,我用小学时学到的一些知识,自以为写出了前两题。 不料最终只获得了 30/300 分的 "高分",排在榜单的最后几位。

不过我没有难过。毕竟一起集训的都是大哥哥和大姐姐。记得当时认识了几位刚结束中考的,常州一中的学长。他们几个性格很好,不嫌弃我年龄小,经常带我一起玩。 每次考试进行到一半,他们便打开 U 盘里的游戏,开始 "颓废"。 我有时帮学长们完成没做完的题,有时也加入他们的“颓废”行列。 此外,我还第一次见到了传说中的樊AU (昵称) 大佬。他平易近人,水平也确实很高,就是有些羞涩。

除了考试外便是专题讲座了,当时,讲课的老师主要是一些学生教练。经过几天的学习,我受益匪浅。

扬中的天气格外宜人,每天傍晚坐在教室里,一边观赏窗外的夕阳,感受轻柔的夏风,一边思索老师上课时介绍的那些算法。

这种简单的快乐,似乎在我进入初中后,就再也找不到了。

集训结束后,教练找到我,问我愿不愿意初中参加信息学竞赛,我想都没想就答应了。

万万没想到,从此走上了一条与众不同的道路。

[初中]

初一的生活是幸福的, 那时的课业压力并不大, 虽然我的学习态度很烂, 但考试也少有不在班级前十的时候 (数学英语经常前五)。与此同时,我还参加了全国奥林匹克信息学联赛 (NOIP) 初中组的比赛, 顺利获得了全国一等奖,排名全省第 31。

然而, 我并没有投入太多时间学习编程,而是像其他同学那样享受初中生活。当时的我,也不懂得信息学竞赛和小学的编程考试有多么大的差异。

初一下学期时, 我偶然在互联网上看到了一位山东的学姐写下的信息学竞赛回忆录 (链接在 这里) , 给我带来了极大的震撼。 在此之前我从未想过,竞赛的道路是如此残酷。一直以来,我都认为我可以像省常中的许多前辈一样,"按部就班" 地进省队,拿奖牌, 进入理想的大学。然而,我忽视了他们为此付出的努力。

我并不想获得像那位学姐那样惨痛的结局, 我必须提前开始准备。

于是 ,接下来的暑假里,我放弃了一切外出玩耍的机会,每天七点就开始做题,那时我选用的教材是李煜东写的 << 算法竞赛进阶指南 >>。在两个月的时间里, 我完成了所有内容的学习,并亲自实现且通过了书上 600 多道例题。在这个过程中,我逐渐蜕变为一名真正的,训练有素的 OI 选手。

功夫不负有心人。 暑假结束后, 我开始在省常中每周的例行训练中取得领先,作为年龄最小的选手, 我几乎每次都能在 100 多人中取得前三的成绩,甚至拿过很多次第一,成为了一时的风云人物。 在此期间, 我还结识了许多从外地来常州集训的学长学姐们,他们给予了我许多关心与支持。

优异的训练成绩使我天真的认为,自己可以在联赛中取得 450 分以上的高分。记得当时,我还早早给自己树立了拿金牌,保送清北的最高理想。

不料那年的联赛我意外地考得很差, 只获得了 296/600 的分数, 离全国一等奖分数线都差了 15 分左右。 由于花费了大量时间进行训练,我的文化课成绩也一落千丈。联赛结束后的校内期中考,我从班级前十直接跌至倒数,成为不折不扣的差生。

次年四月,我去南京参加了省队选拔比赛,那是我第一次参加如此高级别的赛事。尽管尽全力打满了所有的暴力分,我的最终排名仍是全省垫底 (在 130 名选手中排名第 109) 。在那场比赛中,徐翊轩学长力压众多南外选手,成为江苏省省队队长。而我的分数连他的四分之一都不到。这让我第一次体会到与高手之间存在的巨大差距。

一连串的打击使我彻底迷失了方向。 那段时间,校内语文课正学到 << 未选择的路 >> 这篇课文。

黄色的树林里分出两条路,

可惜我不能同时去涉足,

我在那路口久久伫立,

我向着一条路极目望去,

直到它消失在丛林深处。

但我却选了另外一条路,

它荒草萋萋,十分幽寂,

显得更诱人、更美丽;

虽然在这两条小路上,

都很少留下旅人的足迹;

虽然那天清晨落叶满地,

两条路都未经脚印污染。

呵,留下一条路等改日再见!

但我知道路径延绵无尽头,

恐怕我难以再回返。

也许多少年后在某个地方,

我将轻声叹息把往事回顾:

一片树林里分出两条路,

而我选了人迹更少的一条,

从此决定了我一生的道路。

第一次读这首诗时,我差点哭了出来。我又何尝不是选择了一条少有人走的道路呢?然而,付出如此多的努力,我究竟得到了些什么?是那张可笑的二等奖证书,糟糕的省选排名,还是一塌糊涂的学习成绩?曾尝试和班级里的同学诉说我的处境,然而似乎很少有人能够理解。总感觉自己和同龄人的共同语言越来越少了。

是啊,大家在乎的都是游戏,体育,恋爱,还有学校里的成绩,我的破竞赛又算得上什么呢?

记得那段时间,我时常彻夜不眠 (当时正值长个子的关键时期,也许这也是我长不高的一个原因吧 (笑)) ,一次又一次怀疑自己是否做出了正确的选择。 每天晚上都要和母亲进行很久的谈话 (在此感谢我的家人陪我度过了最艰难的岁月)。

好在我逐渐学会了坚强, 明白了失误是竞赛中不可避免的事情。"自己选择的路,跪着也要走完",每当我想要放弃时,便用陈立杰学长的这句名言给自己加油打气。

省选结束后,我并没有花太多时间进行训练。不过, 我对初二的比赛进行了系统性的分析,发现自己最主要的问题是没有重视提升自己的思维水平。 虽然我花了大量时间钻研高级数据结构和算法 (网络流,FFT,Link-Cut-Tree, 轻重链路径剖分,后缀自动机 ,点分治等等), 然而, 我却无法很好的应用它们。

开始意识到, 信息学竞赛的核心是 Problem-Solving Skills (解题能力) , 而不是写代码的能力或者是掌握很深奥的数据结构与算法。

于是我通过参加一些国外网站 (Codeforces, Atcoder, USACO...) 上举办的比赛,重点提升自己的解题能力。初二升初三的暑假里,我成功在 Codeforces 上获得了 Candidate Master 头衔, 并且晋级 USACO 铂金组(最高级别)。

高效的训练方式使我在初三那年的联赛中取得了很理想的成绩,高出全国一等奖分数线 158 分, 在江苏省包括所有高中生在内排名第 39 。 我也提前 9 个月就被保送进江苏省常州高级中学创新实验班。除此以外, 我还获得了全国信息学冬令营, 亚太地区信息学奥赛,以及清北冬令营的入围资格。

看到成绩后,我长舒一口气,心想自己终于把握住了一次机会。

然而,更大的挑战还在等着我。

联赛过后的第一场比赛便是清北冬令营了。 虽然教练强烈建议我选择计算机更强的清华, 由于更喜欢北大的人文关怀而非清华又红又专的氛围, 我申请了北大。

在北京的三天里,我参加了两场比赛和三场面试。比赛中的试题似乎有些超出我的能力范围,我只取得了 161/600 的成绩。靠着年龄优势和面试中较好的发挥,我最终勉强拿到三等约。也正是在这场比赛中,我的同学 (也是朋友) 俞神在第二天轻松取得了 200+ 的分数, 拿到一等约。一年前他还在参加初中生的比赛,可如今却已远远超越了我。

第一次意识到,天赋对于学习竞赛是如此重要。

为了准备接踵而来的省选,寒假里,我去浙江金华参加了正睿 (信息学培训机构) 组织的十连测。虽然几次考试的成绩并不算太差,但培训的内容却什么也听不懂。集训营里,给我留下最深印象的几位大佬,一位是青岛二中的张艺缤,他虽然上课一直在打游戏,可是每次模拟赛都能取得接近满分的成绩。另一位是人大附中的许庭强,他和我一样,也是初中生,却已经打上了 Codeforces IGM (两年后,他代表中国队,在国际奥赛中取得金牌,而且是全球最高分) 。还有来自南京外国语学校的徐源,他也许是我见过最爱装弱的 OI 选手了。不过,此人虽然声称自己 "又懒又菜" 并且 "课内一塌糊涂", 其实每天都补题补到半夜,并且在训练中的成绩和张艺缤差不多。

跟他们相比,我可能是真的又懒又菜吧。虽然付出大量精力准备,我最终还是考砸了。 俞神获得了 300+ 的成绩,差点初三就进了省队。而我的分数只比他的三分之一多一点。有时真的感到很好奇,为什么别人轻松做出的题目,我却怎么想都想不出来呢?惨痛的失利让我再次对自己产生了怀疑。

不过,也许是因为年轻时的一腔热血,我还是选择了咬牙坚持,并取得了一些意料之外的成果。 初三到高一的暑假里, 我在由于疫情延期举行的全国冬令营中收获竞赛生涯第一枚奖牌 - 是一枚铜牌。 随后, 我又在亚洲和太平洋地区信息学奥林匹克竞赛 (APIO) 中, 收获第二枚奖牌 - 这次竟然是一枚金牌。 曾以为我的智商可能一辈子都与奥赛金牌无缘,然而却在初三就成功了。这让我感到十分惊喜。 最后一次以初中选手身份参加比赛,是全国信息学奥林匹克竞赛 (NOI) 的线上同步赛, 获得了银牌分数线上的成绩。这三枚奖牌,让我重新找回了一些自信。

看到有学长成功获得 NOI 金牌,入选国家集训队,而有些只能回到教室学文化课,短短两天内许多人的人生轨迹都被改写,心中百感交集。那年,教育部出台了强基计划,这意味着竞赛生在择校中获得的优势被大大减少了,使得这条道路变得更加残酷。

[高中]

然而, 我仍然在进入高中的第一个月时就选择了停课训练。 而我做出此决定的原因,正是因为一些优秀前辈们的故事激励了我。

比如本校的陆明琪学姐,她在高二那年的比赛中遭遇了滑铁卢般的失利,只获得了铜牌。 更不幸的是,强基计划的出台又让她通过铜牌拿到的武汉大学有条件录取协议成为废纸。但她在高一高二完全没上课的情况下,仅通过高三一年的努力就裸分考入了清华大学计算机系,随后又在高手如云的清华校测中考进姚班。

记得那年比赛结束后,她在 QQ 空间里说 : 上帝明目张胆的不公平,但凡人保留偏执的权利。

我想,每个人都需要她身上的那股闯劲。我对自己说, 趁年轻,不要辜负心中梦想的声音。

训练是艰苦的,我在博客中记录了当时所做的题目 九月训练记录 和 十月训练记录

十一月的联赛,我取得了 249/400 的成绩,排名江苏省第 14 名。 随后,我在全国信息学冬令营 和 亚太地区信息学奥赛中收获两枚银牌,并参加了清华大学信息学冬令营,获得二等约 (对应曾经的高考降 60 分录取协议)。

紧接着的省选是异常重要的比赛。

我废寝忘食地准备,甚至连除夕夜都在电脑前思考问题。

然而,仿佛是命运给我开了个巨大的玩笑 : 我在一试最简单的第一题中犯下了一个极其愚蠢却又极其致命的错误 -- 两行代码写反。

记得出成绩的那天,我一大早便来到机房。或许是因为紧张的缘故,等待分数的过程中,我的浑身都被汗水浸湿。而当看到第一题竟然得了 0 分后,我顿时感到大脑一片空白。

也许我可以接受因题目太难,技不如人而被淘汰;然而,如此荒唐的结局是我从未想过的。

多么讽刺啊,全省前 30 名选手,所有人第一题都得了满分, 唯独我的零分格外显眼。其实第二天的成绩很好 (275 / 300, 全省第 6 名),然而这又有什么用呢?最终我以标准分 5 分的差距与省队失之交臂。

众人面前,我装作一副无所谓的模样。直到一起训练的同学们都离开了机房。 那一刻,我彻底崩溃了。

与其说对比赛结果的不满和对前途的担忧,更令我感到悲哀的是,自己仿佛从未被他人理解过。 由于童年创伤,一直以来我都是一个很脆弱很自卑的人,总是幻想着在国赛中拿到金牌,通过这样巨大的胜利找到自信。而和我朝夕共处的其他 OIer 们都拥有良好的心态, 他们没有我这样重的思想包袱。

"快乐是别人的,我什么都没有"。

记得初二那年,一位女同学在美术课上嘲笑我 "除了会写程序一无所有",那天我难受得哭了一整晚。然而,现在我连信息学竞赛也失败了。

回教室后,我将不可避免地面对一些尖酸刻薄的同学们的恶毒讽刺,和部分令人作呕的学生家长们的闲言碎语。

虽然竞赛生涯一次又一次的失利已经让我磨练出强大的抗打击能力,这次失败使我开始自暴自弃。

那段时间我成为了一个彻头彻尾的坏学生,经常上课睡觉,翘课,打游戏,和一些同样不学习的朋友到处鬼混。我的文化课成绩随之直线下降,时常在班里垫底。

经过很长一段时间的沉沦后, 我开始重新思考自己的未来。

也许是时候想想自己要什么了。 我问自己,参加信息学竞赛是真的因为热爱吗? 还是只是享受那种碾压别人的变态快感,或是为了给自己逃避现实,逃避文化课找借口, 又或是为了纯粹的功利心和虚荣心?

各种原因都有吧, 唯独我对算法的热爱, 好像从很久以前就已经失去了。

停课训练使我成为了一个和普通高中生截然不同的 "怪人"。不仅学业成绩一塌糊涂,而且性格愈发暴躁。总是因为一两场比赛和训练就开始怀疑、否定自己。

然而,也许我真的只是个普通人吧。突然理解了学姐博客中的那句话 "优秀与顶尖之间有着难以逾越的差距。 而这条路的残酷性在于,它只属于最顶尖的那些人"。 想想每次外出集训都能碰到一些既有天赋又努力的大佬,同龄人中,南外的戴江齐同学已经打上了 Codeforces LGM。即使我进入了省队, 也大概率无法在更加残酷的国赛中获得金牌。

是时候该退出了吧!竞赛已经对我的心理健康产生了太多负面影响, 我的人生价值也不该被绑定在这样一个赌博性质极强的智力游戏上。况且我早已不热爱它了。

在网上了解到了许多信息,突然发现出国留学是一个很好的想法。毕竟,国外的高校可以提供很多国内无法提供的资源。计算机并不等于算法竞赛,进入一所世界领先的高校,学习一些 state-of-art techniques, 是更加重要的事情。如果我在国内参加高考, 很有可能只能考上一所普通高校 (毕竟停课时间太久了),并浪费四年宝贵的青春。

唯一的缺点恐怕就是需要父母多花钱了, 我是普通老百姓的孩子,我的家庭并没有那么富裕。 然而,也许我可以参加 AP 考试省下一年的学费和生活费;在大学里, 我也可以通过拿奖学金和实习的方式减轻家里的负担。

好在我的家人非常开明,都支持我的决定。

这时候我的教练告诉我,CCF 给每个省都下发了奖励名额,我作为学校省队线外的第一名,可以以 D 类选手 (编号 JS - 0021) 的身份参加决赛,但是无法保送。

也就是说我还是进入了省队。 然而这不重要了,因为我已经决定,这场比赛后就淡出算法竞赛,也就是基本退役了。

从那时起, 我的重心便从信息竞赛转向了备战托福和 AP 等标化考试。 有时候也会回班学一些文化课 (主要是数学)。

那年暑假举行的国赛, 由于准备不充分, 我最终只获得了一个铜牌中上段的名次。 作为江苏选手真的有些丢人。

颁奖典礼上,看着许多熟悉的人都拿到了金牌。

多么希望我也是他们中的一员啊!

虽然早有准备, 但一直求胜心切的我还是受不了这样的冲击, 我感到我的心如撕裂般疼痛。

于是,颁奖典礼还没结束,我便直奔火车站,也彻底告别了陪伴我 4 年的信息学竞赛。

也许人生总要有点遗憾吧, 回程的火车上,我这样安慰自己。 如果任何事情都顺风顺水,好像也没什么意思呢。

接下来的一年里,我离开机房,回归了久违的集体生活。无论是课堂上,还是运动会,文艺汇演等活动中,同学们的精彩表现都让我意识到,评价一个人的标准不应是单一的。我开始逐渐走出曾经那个封闭的小圈子,拥抱崭新的生活。

高三那年的申请季,我通过 108 分的托福成绩和 9 门 AP 大学先修课,收获了加拿大不列颠哥伦比亚大学 和 麦吉尔大学的 offer,终于给我的高中画上了一个较为圆满的结局。

[退役后]

如今,我已踏入大学的新阶段。在大学里,重新发现对算法的热爱,与志同道合的朋友深入交流,接触不同文化背景的异国友人,让我逐渐明白人生的多样性与丰富性。

努力工作,享受生活,我开始领悟到人这一生需要平衡。

竞赛给我留下的烙印终究会被岁月慢慢溶解,如今回想起当初那段努力奋斗的过往,突然感到很是怀念,心中也慢慢放下了许多。而回顾学习 OI 时的心态,仿佛那时有些幼稚、狭隘。其实人的潜力是多方面的,需要将视野放得更加开阔。

有位前辈的话说得好, "人生如此复杂, 机会多得像稠密图, 我们没有理由认输, 尽管我们走不了最短路, 但图仍是连通图, TLE之前, 没有一个节点叫失败"。

对于仍在 OI 征途上的同学们,我想说:你们的坚持是正确的,每一次努力都是值得的。希望机房里的日子成为你们生命中一段难以忘怀的记忆,在这连通图的人生旅程中,愿你们找到属于自己的光芒,踏上一条通向梦想的独特之路。

[致谢]

最后我想感谢一些在竞赛道路上给我提供鼓励与支持的人 (如果有遗漏很抱歉)

长辈:

我的家人

曹文教练

秦新华教练

何静老师

许晓伟老师

吴涛老师

学长学姐 :

濮成风

吴之琛

陈柘宇

李泽清

陆明琪

同届机房的朋友们 :

杨济源

何润元

陆华均

俞越

王子尧

许天祺

杨子烆

杨砚泽

刘兆洲

樊书岩

王钧澎

难忘和你们共同进步的那段时光, 难忘机房里的欢声笑语!

学弟:

赵海鲲

外校的朋友们 :

杜以

李新年

孙从博

万天航

刘孟博

桑田

黄旭

龚可

袁天骏

Foreign Competitive Programmers :

Vahagn Grigoryan (Armenia)

AmirReza PourAkhavan (Iran)

Lara Semeš (Croatia)

还有很多教室里的同学们, 就不一一列举了!

小有遗憾的 NOI2021

那年在北大

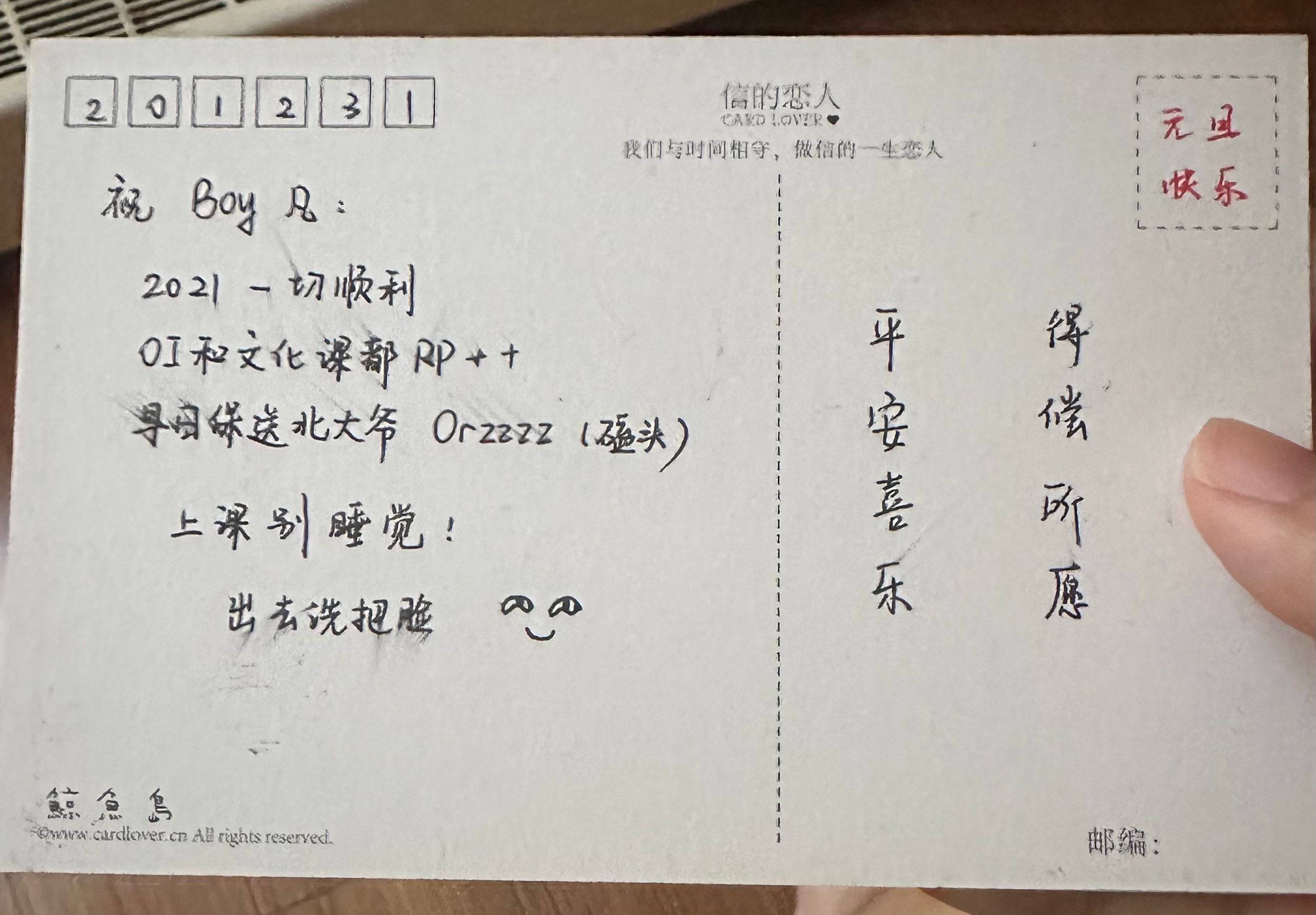

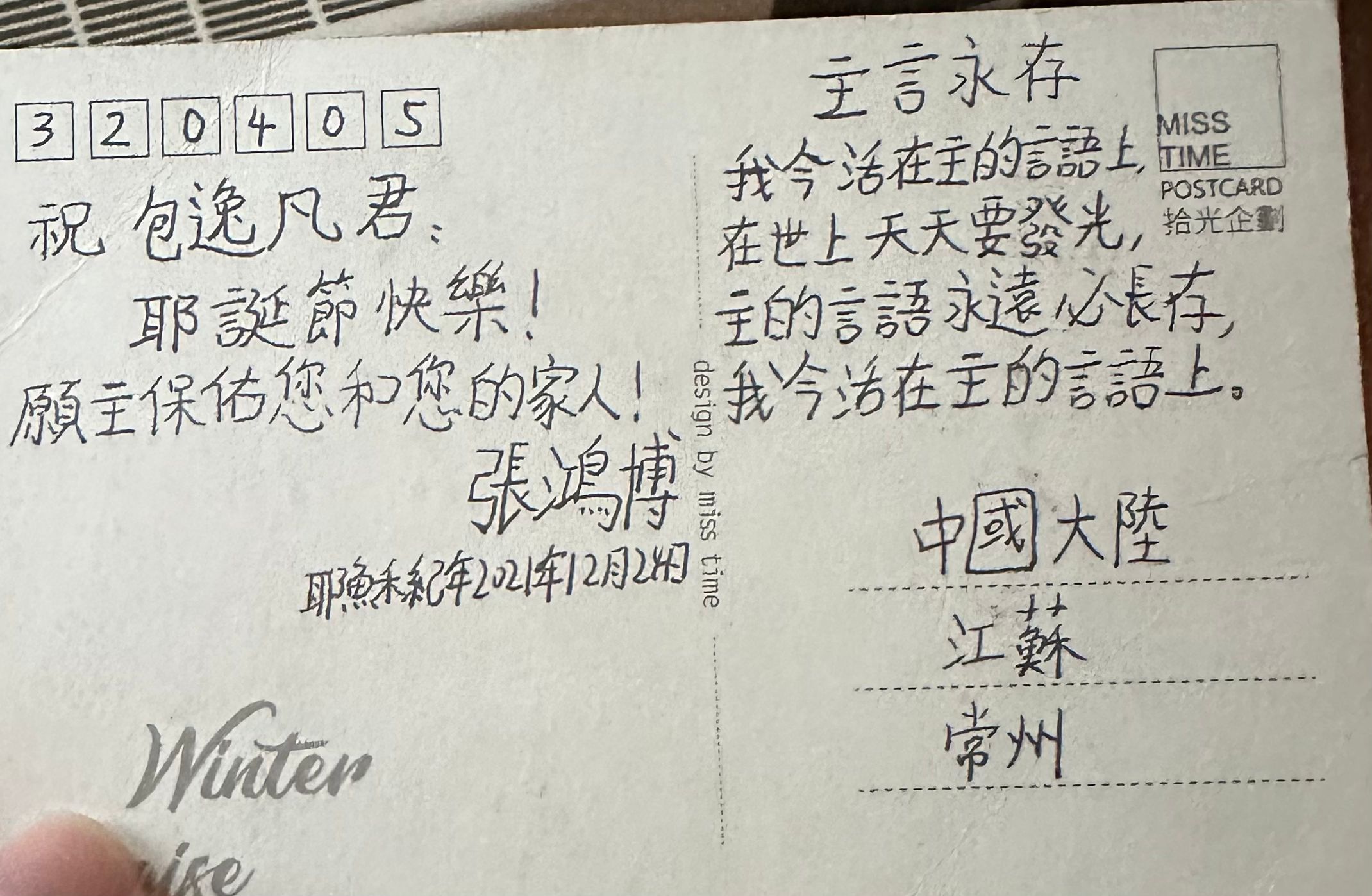

省选前的那个圣诞节, 同学们给我写的贺卡, 至今看了还是很感动!

我的大学校园

Reference :

Ten Years of Competitive Programming - AmirReza PourAkhavan

亲爱的朋友,感谢你阅读本文!

本人的文字水平较差,并且部分段落写得有些矫情。 但是大多是我的真情实感!希望能够包容。

再次感谢!祝你拥有美好的一天!

EVENBAO

Dec 1st 2023, Vancouver

[ENGLISH]

Preface

Ever since I retired from NOI 2021, I have gradually faded away from algorithm competitions for more than two years. Suddenly, I felt compelled to write this memoir to commemorate those days of burning passion and youthful intensity.

Elementary School

Unlike many other competition students, I did not grow up surrounded by praise and encouragement from teachers and classmates during my elementary years. I showed no extraordinary talent at the time; instead, I was an unequivocal misfit in my class. Perhaps my “awakening” came later than that of my peers—until second grade, I still could not climb stairs; during physical education running tests, I was always the very last; and even the simplest calisthenics routines, no matter how hard I tried, eluded me.

Worse still, I encountered a class teacher of extremely poor character. Not only did she never offer me any help, but she also constantly blamed me for dragging down the class and resorted to caustic sarcasm. I still remember the time when a classmate, in one of his essays, depicted me as a clown—replete with a series of “jokes” about my antics, including the “ugly” behavior of being too afraid to participate in physical education for fear of ridicule. To my dismay, my teacher read his essay aloud in front of the entire class, utterly disregarding my feelings. With every passage she read, the class burst into laughter. It was as if everyone relished building their joy on the foundation of my suffering.

Encountering the cruelty of human nature at such an early age forged in me a character starkly different from others. I came to despise collectivism so deeply that, even up to high school, I rarely participated in group activities—be it spring outings, autumn excursions, or even graduation ceremonies. At the same time, I became exceedingly competitive. In later years, it was precisely this overwhelming desire to prove myself that eventually led me onto the path of competitions.

In fifth grade, because I did not earn an “excellent” grade in both physical education and art, I began to worry about school selection. At that time, to gain admission to one of the better private middle schools in the city, it was imperative to receive an “excellent” in every subject; otherwise, one was doomed to attend an ordinary public school. Moreover, in Jiangsu, fewer than fifty percent of the public school students would advance to high school. My parents, lacking any influential connections, could not help me “get in through the back door” to a private middle school.

So, what was to be done? The only recourse was to achieve outstanding results in programming or math competitions and thereby earn special admission. In the end, I chose to focus on studying programming. I made this decision partly because I had taught myself how to type in first grade and thus believed I possessed a certain aptitude for computers.

Unlike many other cities, Changzhou boasted an extremely well-developed informatics training system that exposed many high-achieving students to programming at a very early age. When I joined the training class in the second half of fifth grade, I recall that some of my peers had already been learning for more than two years. Needless to say, the gap between us was enormous. In the very first few lessons, I was completely bewildered. Lacking genuine passion, my attitude toward learning was poor. Whenever I came across a problem I couldn’t solve, I would surreptitiously fire up a small game that a classmate had given me, and so I entertained myself.

Unexpectedly, during a classroom test in the advanced class, I inadvertently outperformed the others—and from that moment, I developed a profound interest in programming. My performance in class began to stand out. By the following autumn, I had become the best student in the training class. Soon after, through self-study of fundamental algorithms such as depth-first search (DFS), breadth-first search (BFS), and binary search, I leaped ahead by three levels. Thanks to my excellent performance—and with the recommendation of Teacher He Jing—I was admitted to Changzhou High School in Jiangsu Province, where I received more formal and professional training in programming.

I vividly recall that every evening, after finishing my homework, I would sit in front of my computer and practice programming. It was the first time I had ever worked so relentlessly toward a specific goal—and, driven by passion, I truly enjoyed the process.

In the second semester of sixth grade, during the citywide programming competition, I managed to distinguish myself among more than 300 competitors by securing first place in the entire city. As a result, I was admitted four months in advance to Changzhou Foreign Language School. When people saw my results, they were astonished—no one had expected that someone whose name was previously unknown would achieve the highest score.

Those subsequent four carefree months taught me an important lesson: to keep at bay those people and situations I despised and to obtain genuine freedom, one must become strong enough oneself. Thus, the gloomy days of elementary school finally came to an end, and a new life began.

Junior High

During the summer vacation before entering junior high, I attended—for the very first time—a provincial informatics training camp held in Yangzhong, Zhenjiang. The coach felt that the problems prepared for the junior high group might be too easy for me and thus had me experience the high school level. In that first exam, relying on some of the knowledge I had picked up in elementary school, I naïvely believed I had solved the first two problems. Instead, I ended up scoring only 30 out of 300 points—“high” only in quotation marks—and was ranked among the very bottom.

Yet I was not upset. After all, the training camp was attended by older “big brothers and sisters.” I met several senior students from Changzhou No. 1 High School who had just finished their entrance exams. They were kind-hearted and did not mind my youth; they often invited me to join them in play. Halfway through each exam, they would pull out a USB loaded with games and begin to “slack off.” Sometimes I would help them finish unsolved problems, and at other times, I would join in their idleness. It was also during this camp that I met for the first time the legendary “Fan AU” (a nickname)—a person who was as approachable as he was talented, though admittedly a bit shy.

Aside from the tests, there were also specialized lectures—mostly delivered by student coaches. In just a few days of study, I benefited immensely. The weather in Yangzhong was exceptionally pleasant; each evening I would sit in the classroom, gazing at the sunset outside the window and feeling the gentle summer breeze as I pondered over the algorithms introduced by our teachers. It seemed that such simple happiness would never be found again once I entered junior high.

After the training camp, the coach approached me and asked whether I would be willing to participate in informatics competitions as a junior high student. Without hesitation, I agreed. Little did I know that from that moment on I would embark on a path unlike any other.

My first year in junior high was a happy time. The academic pressure was not overwhelming, and although my study attitude was lackluster, I rarely fell outside the top ten in class examinations (with mathematics and English often placing in the top five). At the same time, I participated in the junior high group of the National Olympiad in Informatics in Provinces (NOIP) and managed to win a national first prize—ranking 31st in the province.

However, I did not devote much time to studying programming; I simply enjoyed junior high life like everyone else. At that point, I did not yet understand the vast difference between informatics competitions and the elementary-level programming tests.

In the second semester of first year, I chanced upon a memoir on the Internet—written by a senior from Shandong about her experiences in informatics competitions (a link was provided)—and it shocked me profoundly. Until then, I had never imagined that the road of competitions would be so brutal. I had always assumed that, like many of the seniors at Changzhou Senior High School, I could simply follow a prescribed path—joining the provincial team, winning medals, and entering my dream university. Yet I had utterly overlooked the immense effort that such achievements demanded.

I did not want to end up with a painful fate like that senior’s; I knew I had to start preparing early. Thus, during the ensuing summer vacation, I sacrificed all opportunities for play and began solving problems at seven o’clock each day. At that time, I chose the textbook Algorithm Competition Advanced Guide by Li Yudong. Over the course of two months, I absorbed all the material and personally implemented and verified over 600 sample problems from the book. Through this rigorous process, I gradually transformed into a genuine, well-trained OI competitor.

Hard work always pays off. After that summer ended, I began to lead in the weekly training sessions at my school. As the youngest competitor, I almost always ranked among the top three out of more than 100 students—and even earned first place on several occasions, becoming something of a rising star. During this period, I also made many acquaintances among senior students from other regions who had come to Changzhou to train; they offered me much care and support.

Buoyed by my excellent training results, I naïvely believed I could score above 450 points in the league competitions. I even set for myself the lofty goal of winning a gold medal and earning direct admission to elite universities such as Tsinghua or Peking University. However, in that year’s league I performed unexpectedly poorly, scoring only 296 out of 600 points—about 15 points short of the national first-prize cutoff. Moreover, the extensive time I devoted to training caused my academic performance to plummet. In the school midterm exams following the league, I fell from the top ten in my class to the very bottom, becoming an unequivocal underachiever.

In the following April, I traveled to Nanjing to participate in the provincial team selection competition—my first experience in such a high-level event. Despite exerting every effort to garner as many “brute-force” points as possible, my final ranking placed me near the bottom of the province (109th out of 130 competitors). In that competition, senior Xu Yixuan outshone numerous students from Nanjing Foreign Language School to become the captain of the Jiangsu provincial team, while my score was less than a quarter of his. For the first time, I truly felt the immense gap between myself and the experts.

A series of setbacks left me completely lost. During that period, our Chinese literature class was studying the poem “The Road Not Chosen.” The verses read:

In a grove of golden trees, two roads diverged,

Alas, I could not tread both paths at once.

I lingered at that fork for a long while,

Gazing intently down one path,

Until it vanished into the depths of the forest.

Yet I chose the other road,

Overgrown with wild grass, serene and secluded,

Appearing far more enticing and beautiful;

Though on both these little roads,

Few travelers left their footprints;

Though that morning, the ground was carpeted with fallen leaves,

Neither road bore any trace of previous steps.

Ah, I leave one road behind, to perhaps meet again another day!

But I know that the paths stretch on unending,

And I fear I shall never be able to return.

Perhaps, many years hence, in some distant place,

I will softly sigh and recall the past:

In a woodland where two roads diverged,

I chose the one less trodden by,

And that has determined the course of my life.

The first time I read that poem, I nearly wept. Was I not, too, someone who had chosen a road less traveled? And yet, after pouring so much effort into my pursuits, what had I truly gained? Was it that ludicrous second-prize certificate, a disappointing provincial ranking, or abysmal academic grades? I tried explaining my plight to my classmates, yet very few seemed to understand. I felt increasingly alienated from the common language shared by my peers, who cared only about games, sports, romance, and school grades—while my miserable competitions hardly seemed to count.

I recall that during this time, I often stayed awake all night (it was the crucial period for growth, which perhaps is one reason I never grew tall [laughs]), repeatedly questioning whether I had made the right choice. Every night, I would engage in long conversations with my mother (and for that, I am forever grateful to my family for guiding me through those toughest days).

Eventually, I learned to be strong and understood that mistakes were an inevitable part of competitions. “If it’s the road you have chosen, you must walk it even on your knees”—whenever I felt like giving up, I would remind myself of these words from senior Chen Lijie.

After the provincial selection, I did not continue training intensely. Instead, I conducted a systematic analysis of the competitions during my second year of junior high and discovered that my primary problem was not honing my problem-solving skills. Although I spent countless hours studying advanced data structures and algorithms—network flow, FFT, Link-Cut Trees, heavy-light decomposition, suffix automata, centroid decomposition, and so on—I found myself unable to apply them effectively. I gradually came to realize that the core of informatics competitions lay in problem-solving skills, not merely in coding or mastering esoteric algorithms.

To address this, I began participating in competitions hosted on international platforms such as Codeforces, Atcoder, and USACO, focusing on improving my problem-solving abilities. During the summer vacation between my second and third years of junior high, I succeeded in attaining the Candidate Master title on Codeforces and was promoted to the USACO Platinum division (the highest level).

This more efficient training enabled me to achieve excellent results in my third-year junior high league—scoring 158 points above the national first-prize threshold and ranking 39th in Jiangsu Province (including all high school students). I was even granted early admission—nine months ahead of schedule—to the Innovative Experimental Class at Changzhou High School. In addition, I qualified for the National Informatics Winter Camp, the Asia-Pacific Olympiad in Informatics, and the Tsinghua-Peking University Winter Camp. Seeing these results, I exhaled a long sigh of relief, thinking that I had finally seized an opportunity.

However, even greater challenges lay ahead. The very first competition after the league was the Tsinghua-Peking University Winter Camp. Although my coach strongly advised me to choose Tsinghua University—given its stronger computer science program—I applied to Peking University because I preferred its emphasis on humanities over Tsinghua’s overly politicized and specialized atmosphere.

During three days in Beijing, I participated in two contests and underwent three interviews. The exam problems seemed to exceed my abilities, and I managed to score only 161 out of 600. Relying on my relative youth and a decent interview performance, I barely secured a third-level admission offer. In that same competition, my friend and classmate Yu Shen, on the very next day, effortlessly scored over 200 and earned a first-level offer. Just a year ago he was still competing as a junior high student—now he had far surpassed me. It was the first time I truly realized how crucial innate talent was in this arena.

In preparation for the subsequent provincial selection, during the winter vacation I attended a series of ten consecutive mock tests organized by Zhengrui, an informatics training institution, in Jinhua, Zhejiang. Although my scores in several tests were not too bad, I found myself unable to grasp the training content at all. At the camp, several outstanding individuals left a deep impression on me. One was Zhang Yibin from Qingdao No. 2 High School—despite playing games during class, he consistently achieved nearly perfect scores in the mock contests. Another was Xu Tingqiang from Renmin University Affiliated High School; like me, he was still a junior high student, yet he had already earned the Codeforces IGM title (and two years later, he represented China at the International Olympiad in Informatics, winning a gold medal with the highest score in the world). I also met Xu Yuan from Nanjing Foreign Language School—a competitor who often pretended to be weak. Despite claiming he was “lazy and incompetent” and that his in-class performance was abysmal, he would, in fact, work on extra problems until midnight; his training scores were comparable to Zhang Yibin’s.

In comparison, I was probably truly lazy and inept. Even after expending tremendous energy preparing, I still performed poorly. Yu Shen scored over 300—almost earning a spot on the provincial team in junior high—while my score was barely a third of his. I often wondered why others could solve problems with ease while I struggled to come up with any solution at all. This painful defeat made me doubt myself yet again.

Perhaps it was the fire of youth that compelled me to grit my teeth and persist despite the setbacks, and I eventually managed to achieve some unexpected successes. Between the summer after junior high and the summer of my first year in high school—at the National Winter Camp postponed due to the pandemic—I won my first competition medal, a bronze. Soon after, I secured a second medal—a gold—at the Asia-Pacific Olympiad in Informatics. I had once believed that my intelligence might forever preclude me from winning an Olympiad gold medal, yet here I was in junior high with a gold in hand—a delightful surprise. The final competition I participated in as a junior high contestant was the online synchronized round of the National Olympiad in Informatics (NOI), where I scored just at the silver-medal threshold. These three medals helped me regain a measure of self-confidence.

When I saw seniors winning NOI gold medals and being selected for the national training team—while others had no choice but to return to the classroom to study—the trajectories of so many lives were rewritten in just a couple of days, and I was filled with mixed emotions. That same year, the Ministry of Education introduced the “Strong Foundation Plan,” which greatly diminished the advantages that competition students once enjoyed during school selection, thereby rendering this path even more brutal.

High School

Nevertheless, in the very first month of high school I made the decision to suspend regular classes and focus solely on training. I chose this path because the stories of several outstanding seniors had inspired me deeply.

For example, our senior Lu Mingqi encountered a devastating defeat in her second year of high school competition, earning only a bronze medal. To make matters worse, the introduction of the Strong Foundation Plan rendered the conditional admission agreement to Wuhan University—which she had secured through her bronze medal—worthless. Yet, despite not attending classes during her first and second years, she managed, solely through her efforts in the third year, to gain admission to Tsinghua University’s Department of Computer Science with an unadjusted (raw) score, and later succeeded in entering the elite Yao Class through the fiercely competitive Tsinghua campus test.

I recall that after that competition ended, she posted on her QQ Space:

“God’s blatant unfairness may be undeniable, but mortals have the right to be stubborn.”

I thought that everyone needed to possess that spirit of daring. I told myself, while I am still young, I must not betray the voice of the dreams in my heart.

The training was grueling. I even documented the problems I solved in my blog under titles such as “September Training Record” and “October Training Record.” In the November league, I scored 249 out of 400 points—ranking 14th in Jiangsu Province. Soon after, I won two silver medals at the National Informatics Winter Camp and the Asia-Pacific Olympiad in Informatics, and I attended the Tsinghua University Informatics Winter Camp where I secured a second-level offer (comparable to what used to be a 60-point reduction in the college entrance exam for admission agreements).

The subsequent provincial selection was an exceptionally important competition. I prepared with such unremitting diligence that even on New Year’s Eve I was hunched over my computer, pondering problems. Yet fate played a cruel joke on me: in what was meant to be the simplest first problem, I made an extremely foolish yet fatal mistake—reversing two lines of code.

I remember arriving at the computer lab early on the day the results were released. Perhaps because of nerves, I was drenched in sweat while waiting for my scores. And when I saw that I had scored 0 on the first problem, my mind went completely blank. Perhaps I could have accepted elimination if the problem had been too hard or if my skills were inferior, but such an absurd outcome was something I had never anticipated. How ironic that among the top 30 competitors in the province, everyone had scored full marks on the first problem—except me, whose zero stood out so starkly. In fact, my score on the second day was very good (275 out of 300, ranking 6th in the province), but what use was that? In the end, I missed joining the provincial team by a margin of 5 standard points.

In front of everyone, I feigned nonchalance. It was only after all my training mates had left the computer lab that I completely broke down. More than my dissatisfaction with the result or worries about the future, what pained me most was the sense that I had never truly been understood. Due to childhood traumas, I had always been fragile and insecure, constantly fantasizing about winning a gold medal at the national competition to gain confidence through such a monumental victory. In contrast, the other OI competitors with whom I spent my days maintained a healthy mentality—they did not carry such heavy burdens of self-doubt.

“Happiness belongs to others; I have nothing.”

I still remember that in my second year of junior high, a female classmate mocked me during art class by saying, “You can do nothing except write programs.” I was so distraught that I cried all night. And now, having failed even in informatics competitions, I dreaded returning to the classroom—knowing that I would inevitably face vicious ridicule from some of my acerbic classmates and the petty gossip of certain obnoxious parents. Although my repeated failures in competitions had already tempered me to withstand setbacks, this defeat drove me into self-abandonment.

During that period, I became a thoroughly wayward student—sleeping in class, skipping lessons, playing games, and aimlessly hanging out with others who also neglected their studies. Consequently, my academic performance plummeted, and I often ranked at the bottom of my class.

After a long period of despondency, I began to reconsider my future. Perhaps it was time to truly ask myself what I wanted. Was my participation in informatics competitions driven by genuine passion? Or was it merely the perverse thrill of crushing others, an excuse to escape reality and academic responsibilities, or simply motivated by utilitarian concerns and vanity? There may have been many reasons—but my love for algorithms had long since faded.

Suspending regular classes for training turned me into someone utterly different from the average high school student—a “weirdo” in many respects. Not only did my academic performance deteriorate dramatically, but my temperament grew increasingly volatile; I would begin doubting and negating myself after every one or two competitions or training sessions. Yet, perhaps I was indeed just an ordinary person. I suddenly understood a line from a senior’s blog:

“There is an insurmountable gap between excellence and the very top. The brutality of this path lies in that it belongs only to the absolute best.”

Every time I attended external training camps, I encountered prodigiously talented and hardworking individuals—for example, among my peers, Dai Jiangqi from Nanjing Foreign Language School had already earned the Codeforces LGM title. Even if I managed to join the provincial team, it was highly unlikely that I would win a gold medal in the even more brutal national competition.

It was time to quit, wasn’t it? Competitions had already taken too heavy a toll on my mental health, and my self-worth should not be bound to such a gamble-like intellectual pursuit. Besides, I no longer loved it.

After gathering extensive information online, I suddenly realized that studying abroad was an excellent idea. After all, foreign universities can offer resources that domestic institutions cannot. Computer science is not synonymous with algorithm competitions; entering a world-leading university to learn state-of-the-art techniques is far more important. If I were to take the college entrance exam in China, I might very well end up at an ordinary university—especially after having missed so many classes—and thus waste four precious years of my youth.

The only drawback might be that it would require my parents to spend more money. I am the child of ordinary people, and my family is not particularly wealthy. However, perhaps I could take AP exams to save on a year’s worth of tuition and living expenses; and in college, I could alleviate the financial burden by earning scholarships and securing internships.

Fortunately, my family is very open-minded and supported my decision.

At that moment, my coach informed me that the CCF had allocated reward quotas for each province. As the top non-provincial team member from my school, I was eligible to participate in the finals as a Class D competitor (numbered JS–0021), though without the guarantee of direct admission. In other words, I still made it to the provincial team. Yet that no longer mattered, for I had already decided that after this competition I would gradually withdraw from algorithm competitions—that is, I was essentially retiring.

From that point on, my focus shifted from informatics competitions to preparing for standardized tests such as the TOEFL and AP exams. Occasionally, I would even attend classes to brush up on academic subjects (mainly mathematics). In that summer’s national competition, due to insufficient preparation, I ultimately achieved only an upper–middle-tier bronze ranking. As a contestant from Jiangsu, it was truly embarrassing. At the awards ceremony, I watched as many familiar faces received gold medals—and I couldn’t help but long to be among them. Even though I had prepared for this moment, my ever-competitive spirit could not withstand the impact; I felt as though my heart were being torn apart.

Thus, even before the awards ceremony had concluded, I rushed straight to the train station and bid a final farewell to the informatics competitions that had been part of my life for four years. Perhaps life must always harbor a hint of regret—I consoled myself on the train ride home. After all, if everything went smoothly, life might lose its meaning.

In the following year, I left the computer lab behind and returned to the long-missed rhythms of communal life. Whether in the classroom, at sports meets, or during cultural performances, the brilliant displays of my classmates made me realize that judging a person by a single criterion is unjust. I gradually emerged from my former insular circle and embraced an entirely new life.

In the application season of my third year of high school, with a TOEFL score of 108 and the completion of nine AP courses, I received offers from the University of British Columbia and McGill University in Canada—finally bringing a relatively satisfying conclusion to my high school chapter.

After Retirement

Now, I have embarked on a new stage as a university student. In college, I have rediscovered my love for algorithms, engaged in deep conversations with like-minded friends, and interacted with international peers from diverse cultural backgrounds. These experiences have gradually taught me the richness and diversity of life. Working hard while also learning to enjoy life, I have come to appreciate that balance is essential in one’s journey.

The indelible marks left by competitions will, in time, be softened by the passage of years. When I now reflect on those days of relentless struggle, I feel a deep nostalgia—and many of the burdens I once carried have slowly been lifted. In retrospect, my mindset during my OI days now seems rather naïve and narrow. In truth, a person’s potential is multifaceted, and one must broaden one’s horizons.

As one senior aptly put it:

“Life is as complex as a dense graph, with opportunities abounding. We have no reason to give up—even if we cannot take the shortest path, the graph remains connected. Before TLE, no node is ever called failure.”

To those still pursuing the OI journey, I say this: your perseverance is commendable, and every ounce of effort is worthwhile. May the days spent in the computer lab remain an indelible memory in your lives; and in this connected graph of existence, may you each find your own light and tread a unique path toward your dreams.

Acknowledgments

Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to everyone who offered encouragement and support along my competitive journey (apologies if I have inadvertently omitted anyone).

Elders:

• My family

• Coach Cao Wen

• Coach Qin Xinhua

• Teacher He Jing

• Teacher Xu Xiaowei

• Teacher Wu Tao

Senior Students:

• Pu Chengfeng

• Wu Zhichen

• Chen Zheyu

• Li Zeqing

• Lu Mingqi

Friends from the Computer Lab (My Batch):

• Yang Jiyuan

• He Runyuan

• Lu Huajun

• Yu Yue

• Wang Ziyao

• Xu Tianqi

• Yang Zihe

• Yang Yanze

• Liu Zhaozhou

• Fan Shuyan

• Wang Junpeng

I will never forget the time we progressed together, nor the joyous laughter that echoed through the computer lab!

Junior Student:

• Zhao Haikun

Friends from Other Schools:

• Du Yi

• Li Xinnian

• Sun Congbo

• Wan Tianhang

• Liu Mengbo

• Sang Tian

• Huang Xu

• Gong Ke

• Yuan Tianjun

Foreign Competitive Programmers:

• Vahagn Grigoryan (Armenia)

• AmirReza PourAkhavan (Iran)

• Lara Semeš (Croatia)

And there are many other classmates whom I do not list individually!

【推荐】国内首个AI IDE,深度理解中文开发场景,立即下载体验Trae

【推荐】编程新体验,更懂你的AI,立即体验豆包MarsCode编程助手

【推荐】抖音旗下AI助手豆包,你的智能百科全书,全免费不限次数

【推荐】轻量又高性能的 SSH 工具 IShell:AI 加持,快人一步

· 震惊!C++程序真的从main开始吗?99%的程序员都答错了

· 【硬核科普】Trae如何「偷看」你的代码?零基础破解AI编程运行原理

· 单元测试从入门到精通

· 上周热点回顾(3.3-3.9)

· winform 绘制太阳,地球,月球 运作规律

2018-12-01 [SCOI 2010] 序列操作