GTM148 抄书笔记 Part I. (Chapter I~III)

写在最前面的一点闲话

GTM148是我最开始想学习抽象代数时找到的;然而当时的我过于地菜,看不懂一点便丢掉了。直到最近想开始复习抽代,我又重新发现了这本书。然后发现它的内容挺有深度,而且不是我想象的那么难读懂(雾),于是开坑。

个人认为GTM148不适合初学抽象代数的人看;相比于研究生教材,这本书更像是一本群论字典。想要入门抽象代数的可以左转知乎0003大佬的抽象代数专栏(也是我入门抽象代数的专栏)。

这个系列几乎原封不动地把GTM148上的内容搬了过来(也正所谓“抄书笔记”)。(求轻喷)

Contents

- Contents

- Chapter I. Groups and Homomorphisms

- Chapter II. The Isomorphism Theorems

- Chapter III. Symmetric Groups and -Sets

Chapter I. Groups and Homomorphisms

Permutations

Definition 1.1.1 If is a nonempty set, a permutation of is a bijection . We denote the set of all permutations of by .

In the important special case when , we write instead of . Note that , where denotes the number of elements in a finite set .

Remark Given a rearrangement define a function by for all . This function is an injection because the list has no repetitions; it is a surjection because all of the elements of appear on the list. Thus, every rearrangement gives a bijection. Conversely, any bijection can be denoted by two rows:

and the bottom row is a rearrangement of . Thus, the two versions of permutation, rearrangement and bijection, are equivalent. The advantage of the new viewpoint is that two permutations in can be "multiplied," for the composite of two bijections is again a bijection.

Cycles

Definition 1.2.1 If and , then fixes if and moves if .

Definition 1.2.2 Let be distinct integers between and . If fixes the remaining integers and if

then is an -cycle; one also says that is a cycle of length . Denote by .

Every -cycle fixes every element of , and so all -cycles are equal to the identity. A -cycle, which merely interchanges a pair of elements, is called a transposition.

Definition 1.2.3 Two permutations are disjoint if every moved by one is fixed by the other. In symbols, if , then and if , then . A family of permutations is disjoint if each pair of them is disjoint.

Proposition 1.2.4(the cancellation law for permutations) If either or , then .

Proposition 1.2.5 If and are disjoint permutations, then ; that is and commute.

Definition 1.2.6 A permutation is regular if either has no fixed points and it is the product of disjoint cycles of the same length or .

Proposition 1.2.7 A permutation is regular if and only if is a power of an -cycle ; that is, for some .

Proposition 1.2.8 If is an -cycle, then is a product of disjoint cycles, each of length .

Factorization into Disjoint Cycles

Theorem 1.3.1 Every permutation is either a cycle or a product of disjoint cycles.

Proof

The proof is by induction on the number of points moved by . The base step is true, for then is the identity. If , let be a point moved by . Define , where is the smallest integer for which . We claim that . Otherwise, for some ; but , and this contradicts the hypothesis that is an injection. Let be the -cycle . If , then is the cycle . If and consists of the remaining points, then and fixes the points in . Now . If is the permutation with and which fixes , then and are disjoint and . Since moves fewer points than does , the inductive hypothesis shows that , and hence , is a product of disjoint cycles.

■

Definition 1.3.2 A complete factorization of a permutation is a factorization of as a product of disjoint cycles which contains one -cycle for every fixed by .

Theorem 1.3.3 Let and let be a complete factorization into disjoint cycles. This factorization is unique except for the order in which the factors occur.

Proof

Disjoint cycles commute, so that the order of the factors in a complete facatorization is not uniquely determined; however, we shall see that the factors themselves are uniquely determined. Since there is exactly one -cycle for every fixed by , it suffices to prove uniqueness of the cycles of length at least . Suppose is a second complete factorization into disjoint cycles. If moves , then for all . Now some must move ; since disjoint cycles commute, we may assume that . But for all , and so we have . The cancellation law gives , and the proof is completed by an induction on .

■

Proposition 1.3.4 Let be a prime and let . If , then either , is a -cycle, or is a product of disjoint -cycles.

Even and Odd Permutations

Theorem 1.4.1 Every permutation is a product of transpositions.

Proof

By Theorem 1.3.1

it suffices to factor cycles, and

■

Definition 1.4.2 A permutation is even if it is a product of an even number of transpositions; otherwise, is odd.

Lemma 1.4.3 If , then

and

Definition 1.4.4 If and is a complete factorization into disjoint cycles, then signum is defined by

It is easy to prove that is well defined.

Lemma 1.4.5 If and is a transposition, then

Proof

Let and let be a complete factorization of into disjoint cycles. If and occur in the same , say, in , then , where and . By Lemma 1.4.3,

and so is a complete factorization with an extra cycle. Therefore, .

The other possibility is that and occur in different cycles, say, and , where and . But now , and Lemma 1.4.3 gives

Therefore, the complete factorization of has one fewer cycle than does , and so .

■

Theorem 1.4.6 For all , .

Proof

Assume that is given and that is a factorization of into transpositions with minimal. We prove, by induction on , that for every . The base step is precisely Lemma 1.4.5. If , then the factorization is also minimal: if with each a transposition and , then the factorization violates the minimality of . Therefore, we have

■

Theorem 1.4.7

- A permutation is even if and only if ;

- A permutation is odd if and only if it is a product of an odd number of transpositions.

Proposition 1.4.8 has the same number of even permutations as of odd permutations.

Semigroups

Definition 1.5.1 A (binary) operation on a nonempty set is a function .

Definition 1.5.2 An operation on a set is associative if

for every .

Definition 1.5.3 An expression needs no parentheses if, no matter what choices of multiplications of adjacent factors are made, the resulting elements of are all equal.

Theorem 1.5.4(Generalized Associativity) If is an associative operation on a set , then every expression needs no parentheses.

Definition 1.5.5 A semigroup is a nonempty set equipped with an associative operation .

Definition 1.5.6 Let be a semigroup and let . Define and, for , define .

Corollary 1.5.7 Let be a semigroup, let , and let and be positive integers. Then and .

Groups

Definition 1.6.1 A group is a semigroup containing an element such that:

- for all ;

- for every , there is an element with

It is easy to show that is a group with composition as operation; it is called the symmetric group on . When , then is denoted by and is called the symmetric group on letters.

Definition 1.6.2 A pair of elements and in a semigroup commutes if . A group (or a semigroup) is abelian if every pair of its elements commutes.

Examples 1.6.3

- The set of all integers is an abelian group with ordinary addition as operation: . Some other additive abelian groups are the rational numbers , the real numbers , and the complex numbers .

- Recall that if and and are integers, then means that is a divisor of . Denote the congruence class of an integer by ; that is,

. The set of all the congruence classes is called the integers modulo ; it is an abelian group when equipped with the operation: ; here and . It is easy to prove that these operations are well defined. - If is a field, then the set of all nonsingular matrices with entries in is a group, denoted by , called the general linear group; here the operation is matrix multiplication, is the identity matrix , and if is the inverse of the matrix , then . If , then is not abelian; if , then is abelian: it is the multiplicative group of all the nonzero elements in .

Theorem 1.6.4 If is a group, there is a unique element with for all . Moreover, for each , there is a unique with .

Proof

Suppose that for all . In particular, if , then . On the other hand, the defining property of gives , and so .

Suppose that , then , as desired.

■

As a result of the uniqueness assertions of the theorem, we may now give names to and to . We call the identity of and, if , then we call the inverse of and denote it by .

Corollary 1.6.5 If is a group and , then .

Definition 1.6.6 If is a group and , define the powers of as follows: if is a positive integer, then is defined as in any semigroup; define ; define .

Theorem 1.6.7 If is a semigroup with an element such that:

- for all ;

- for each there is an element with ,

then is a group.

Proof

We claim that if in , then . There is an element with , and . On the other hand, . Therefore, .

If , let us show that . Now , and so our claim gives .

If , we must show that . Choose with , then we have , as desired.

■

Proposition 1.6.8 Let be a group, let , and let and be relatively prime integers. If , then there exists with .

Proposition 1.6.9 Let be a group. For each , the functions , defined by (called left translation by ), and , defined by (called right translation by ), are bijections.

Proposition 1.6.10 Let be a group. For all , we have , , and .

Homomorphisms

Definition 1.7.1

Let and be groups. A function is a homomorphism if, for all , we have .

An isomorphism is a homomorphism that is also a bijection. We say that is isomorphic to , denoted by , if there exists an isomorphism .

Theorem 1.7.2 Let be a homomorphism.

- , where is the identity in .

- If , then .

- If and , then .

Proof

- Applying to the equation gives . Now multiply each side of the equation by to obtain .

- Applying to the equations gives . It follows from Theorem 1.6.4, the uniqueness of the inverse, that .

- An easy induction proves for all , and then .

■

Proposition 1.7.3 Let be a bijection between sets and , then is an isomorphism .

Proposition 1.7.4

- If and are homomorphisms, then so is the composite .

- If is an isomorphism, then its inverse is also an isomorphism.

Proposition 1.7.5 Let be a fixed element of a group , define the conjugation by as by . Then

- is an isomorphism.

- If , then .

Proposition 1.7.6

- A group is abelian if and only if the function , defined by , is a homomorphism.

- Let be an isomorphism from a finite group to itself. If has no nontrivial fixed points and if is the identity function, then for all and is abelian.

Chapter II. The Isomorphism Theorems

Subgroups

Notation We now drop the notation for the operation in a group. Henceforth, we shall write instead of , and we shall denote the identity element by instead of by .

Definition 2.1.1 A nonempty subset of a group is a subgroup of if implies and imply .

If is a subset of group , we write ; if is a subgroup of , we write .

Theorem 2.1.2 If , then is a group in its own right.

Theorem 2.1.3 A subset of a group is a subgroup if and only if and imply .

Definition 2.1.4 If is a group and , then the cyclic subgroup generated by , denoted by , is the set of all the powers of . A group is called cyclic if there is with ; that is, consists of all the powers of .

Definition 2.1.5 If is a group and , then the order of is , the number of elements in .

Theorem 2.1.6 If is a group and has finite order , then is the smallest positive integer such that .

Proof

If , then . If , there is an integer so that are distinct elements of while for some with . We claim that . If for some , then and , contradicting the original list having no repetitions. It follows that is the smallest positive integer with .

It now suffices to prove that ; that is, that . Clearly . For the reverse inclusion, let be a power of . By the division algorithm, , where . Hence, , and so .

■

Corollary 2.1.7 If is a finite group, then a nonempty subset of is a subgroup if and only if imply .

Proof

Necessity is obvious. For sufficiency, we must show that implies . It follows easily by induction that contains all the powers of . Since is finite, has finite order, say, . Therefore, and .

■

Example 2.1.8 If is a group, then itself and are always subgroups. Any subgroup other than is called proper, and we denote this by ; the subgroup is often called the trivial group.

Definition 2.1.9 Let be a homomorphism, and define

the kernel of as and the image of as .

Proposition 2.1.10 Let be a homomorphism, then is a subgroup of and is subgroup of .

Theorem 2.1.11 The intersection of any family of subgroups of a group is again a subgroup of .

Proof

Let be a family of subgroups of . Now for every , and so . If , then for every , and so for every ; hence, , and .

■

Corollary 2.1.12 If is a subset of a group , then there is a smallest subgroup of containing ; that is, if and , then .

Definition 2.1.13 If is a subset of a group , then the smallest subgroup of containing , denoted by , is called the subgroup generated by . One also says that generates .

In particular, if and are subgroups of , then the subgroup is denoted by .

If consists of a single element , then , the cyclic subgroup generated by . If is a finite set, say, then we write instead of .

Definition 2.1.14 If is a nonempty subset of a group , then a word on is an element of the form

where , and .

Theorem 2.1.15 Let be a subset of a group . If , then ; if is nonempty, then is the set of all the words on .

Proof

If , then the subgroup contains , and so . If is nonempty, let denote the set of all the words on . It is easy to see that is a subgroup of containing : ; the inverse of a word is a word; the product of two words is a word. Since is the smallest subgroup containing , we have . The reverse inclusion also holds, for every subgroup containing must contain every word on . Therefore, , and is the smallest subgroup containing .

■

Proposition 2.1.16 If is a field, then the set of all matrices over having determinant , denoted by , is a subgroup of . We call the special linear group over .

Proposition 2.1.17 Let be the set of all even permutations in (and is also called the alternating group on letters), then is a subgroup with elements.

Proposition 2.1.18 Suppose that is a nonempty subset of a set , then can be imbedded in ; that is, is isomorphic to a subgroup of .

Proposition 2.1.19 For any , can be imbedded in , but not in .

Proposition 2.1.20

- For any , can be generated by .

- For any , can be generated by .

- For any , can be generated by the two elements and .

- For any , can be generated by all the -cycles.

Langrange's Theorem

Definition 2.2.1 If is a subgroup of and if , then a right coset of in is the subset of

(a left coset is ). One calls a representative of (and also of ).

Example 2.2.2 If is the additive group of all integers, if is the set of all multiples of an integer (, the cyclic subgroup generated by ), and if , then the coset ; that is, the coset is precisely the congruence class of .

Lemma 2.2.3 If , then if and only if ( if and only if ).

Proof

If , then , and so there is with ; hence, . Conversely, assume that ; hence . To prove that , we prove two inclusions. If , then for some , and so ; similarly, if , then for some , and . Therefore, .

■

Theorem 2.2.4 If , then any two right (or any two left) cosets of in are either identical or disjoint.

Proof

We show that if there exists an element , then . Such an has the form , where . Hence , and so Lemma 2.2.3 gives .

■

Theorem 2.2.4 may be paraphrased to say that the right cosets of a subgroup comprise a partition of (each such coset is nonempty, and is their disjoint union). This being true, their must be an equivalence relation on lurking somewhere in the background: it is given, for , by if , and its equivalence classes are the right cosets of .

Theorem 2.2.5 If , then the number of right cosets of in is equal to the number of left cosets of in .

Proof

We give a bijection , where is the family of right cosets of in and is the family of left cosets. If , define , and it can be verified that is well defined; that is, if , then .

■

Definition 2.2.6 If , then the index of in , denoted by , is the number of right cosets of in .

Proposition 2.2.7 In a finite group , one can always choose a common system of representatives for the right and left cosets of a subgroup ; if , there exists elements so that is the family of all left cosets and is the family of all right cosets.

Definition 2.2.8 If is a group, then the order of , denoted by , is the number of elements in .

Theorem 2.2.9 (Langrange) If is a finite group and , then divides and .

Proof

By Theorem 2.2.4, is partitioned into its right cosets

and so . But it is easy to see that , defined by , is a bijection, and so for all . Thus, , where .

■

Corollary 2.2.10 If is a finite group and , then the order of divides .

Definition 2.2.11 A group has exponent if for all .

Corollary 2.2.12 If is a prime and , then is a cyclic group.

Corollary 2.2.13 (Fermat) If is a prime and is an integer, then .

Proof

Let , the multiplicative group of nonzero elements of ; since is prime, is a field and is a group of order .

Recall that for integers and , one has if and only if in . If and in , then it is clear that . If , then and so , by Corollary 2.2.10; multiplying by now gives the desired result.

■

Proposition 2.2.14 Let have order , where , then has order .

Proposition 2.2.15 If has order and is an integer with , then divides . Indeed, consists of all the multiplies of .

Proposition 2.2.16 If is a finite group and , then .

Proposition 2.2.17 If has finite order and is a homomorphism, then the order of divides the order of .

Proposition 2.2.18 Every subgroup of a cyclic group is cyclic.

Proposition 2.2.19 Two cyclic groups are isomorphic if and only if they have the same order.

Proposition 2.2.20 If is cyclic of order , then is also a generator of if and only if .

Cyclic Groups

Lemma 2.3.1 If is a cyclic group of order , then there exists a unique subgroup of order for every divisor of .

Proof

If , then is a subgroup of order , by Proposition 2.2.14. Assume that is a subgroup of order . Now ; moreover, for some , by Proposition 2.2.15. Then we have for some integer , and . Therefore, , and this inclusion is equality because both subgroups have order .

■

Theorem 2.3.2 A group of order is cyclic if and only if, for each divisor of , there is at most one cyclic subgroup having order .

Proof

If is cyclic, then the result is Lemma 2.3.1. For the converse, recall from the previous proof that is the disjoint union , where ranges over all the cyclic subgroups of and denote the set of all the generators of . Hence, . We conclude that must have a cyclic subgroup of order for every divisor of ; in particular, has a cyclic subgroup of order , and so is cyclic.

■

Theorem 2.3.3 Let be a prime. A group of order is cyclic if and only if it is an abelian group having a unique subgroup of order .

Proof

Necessity follows at once from Lemma 2.3.1. For the converse, let have largest order, say (it follows that for all ). Of course, the unique subgroup of order is a subgroup of . If is a proper subgroup of , then there is with but with ; let . If , then and , a contradiction; we may, therefore, assume that . Now

so that for some integer , by Proposition 2.2.15. Hence, , and so . Since is abelian, , and so . This gives , a contradiction. Therefore, and hence is cyclic.

■

Proposition 2.3.4 A subgroup is a maximal subgroup of if there is no subgroup of with . If is a finite group with only one maximal subgroup, then is cyclic.

Normal Subgroups

Definition 2.4.1 If and are nonempty subsets of a group , then

If , and , then is the right coset . Notice that the family of all the nonempty subsets of is a semigroup under this operation: if and are nonempty subsets of , then , for either side consists of all the elements of of the form with , and .

Theorem 2.4.2 If and are subgroups of a finite group , then .

Proof

Define a function by . Since is a surjection, it suffices to show that if , then . We show that . It is clear that contains the right side. For the reverse inclusion, let ; that is, , , and . Thus, ; let denote their common value. Then and , as desired.

■

Definition 2.4.3 A subgroup is a normal subgroup, denoted by , if for every .

If and there are inclusions for every , then : replacing by , we have the inclusion , and this gives the reverse inclusion .

Proposition 2.4.4 If and , then .

Proposition 2.4.5 Let be a group, then the intersection of any family of normal subgroups of is itself a normal subgroup of .

Proposition 2.4.6 Let be a homomorphism, then the kernel is a normal subgroup of .

Definition 2.4.7 If , then a conjugate of in is an element of the form for some ; equivalently, and are conjugate if for some .

Proposition 2.4.8 If , then if and only if for every conjugation .

Proposition 2.4.9 If is a finite nonempty subset of with , then is a subgroup; however, when is infinite, the statement may be false.

Definition 2.4.10 If and are (not necessarily distinct) subgroups of , then an (-)-double coset is a subset of of the form , where .

Proposition 2.4.11 Let and be subgroups of , then the family of all (-)-double coset partitions .

Proposition 2.4.12 Let and be subgroups of a finite group , and suppose that is the disjoint union

then we have .

Proposition 2.4.13 Let be a finite group, and let and be (not necessarily distinct) nonempty subsets, then either or is true.

Proposition 2.4.14 If and , then .

Definition 2.4.15 If is a subset of , then there is a smallest normal subgroup of which contains ; it is called the normal subgroup generated by , often denoted by .

Proposition 2.4.16 If , then ; if , then is the set of all words on the conjugates of elements in .

Proposition 2.4.17 If and are normal subgroups of , then .

Proposition 2.4.18 If a normal subgroup of has index , then for all .

Quotient Groups

Theorem 2.5.1 If , then the cosets of in form a group, denoted by , of order .

Proof

As operation, we propose the multiplication of nonempty subsets of defined earlier. We have already observed that this operation is associative. Now

Thus, , and so the product of two cosets is a coset. It is easy to prove that the identity is the coset and that the inverse of is .

■

Corollary 2.5.2 If , then the natural map (i.e., the function defined by ) is a surjective homomorphism with kernel .

As for the integer group , the quotient group is equal to , the group of integers modulo . An arbitrary quotient group is often called because of this example.

Proposition 2.5.3 Let , let be the natural map, and let be a subset such that generates , then .

Definition 2.5.4 If , the commutator of and , denoted by , is

The commutator subgroup (or derived subgroup) of , denoted by , is the subgroup of generated by all the commutators.

Theorem 2.5.5 The commutator subgroup is a normal subgroup of . Moreover, if , then is abelian if and only if .

Proof

If is a homomorphism, then because . It follows from Proposition 2.4.8 that .

Let . If is abelian, then for all ; that is, , and so . Thus we have . Conversely, suppose that . For every , we have , and so ; that is, is abelian.

■

Proposition 2.5.6 Let and assume that both and commute with . Then:

- for all ;

- for all .

Proposition 2.5.7 If , denote by and by .

- we have and .

- Jacobi identity .

Proposition 2.5.8 Let be subgroups of and let .

- Three subgroups lemma If and , then .

- If and are all normal subgroups of , then .

The Isomorphism Theorems

Theorem 2.6.1 (First Isomorphism Theorem) Let be a homomorphism with kernel . Then is a normal subgroup of and .

Proof

We have already noted that . Define by . To see that is well defined, assume that ; that is, . Then , and ; it follows that , as desired. Now is a homomorphism:

It is plain that . Finally, we show that is an injection. If , then ; hence , and (note that being an injection is the converse of being well defined). Thus we have shown that is an isomorphism.

■

It follows that there is no significant difference between a quotient group and a homomorphic image.

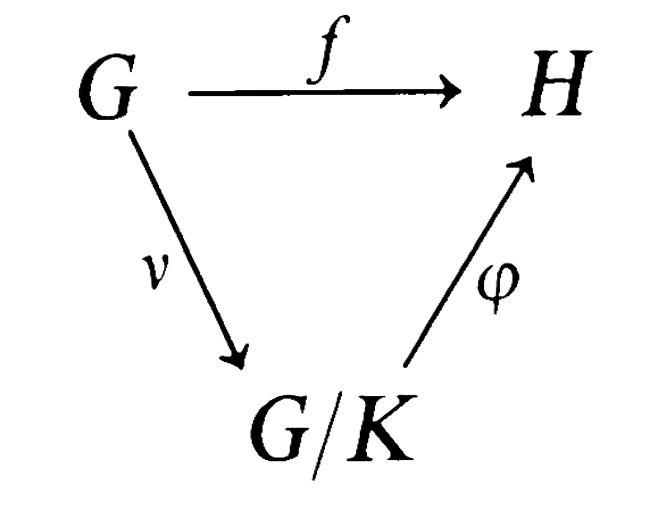

If is the natural map, then the following "commutative diagram" (i.e., ) with surjection and injection describes the theorem:

It is easy to describe : if , then there exists with , and .

Proposition 2.6.2 A homomorphism is an injection if and only if .

Lemma 2.6.3 If and are subgroups of and if one of them is normal, then .

Proof

Recall that and are subsets of containing . If and are subgroups, then the reverse inclusion will follow from Corollary 2.1.12. Assume that . If and , then

where because . Therefore, . A similar proof shows that is a subgroup, and so .

■

Suppose that are subgroups with . Then and the quotient is defined; it is the subgroup of consisting of all those cosets with . In particular, if and is any subgroup of , then and is the subgroup of consisting of all those cosets , where . Since , it follows that consists precisely of all those cosets of having a representative in .

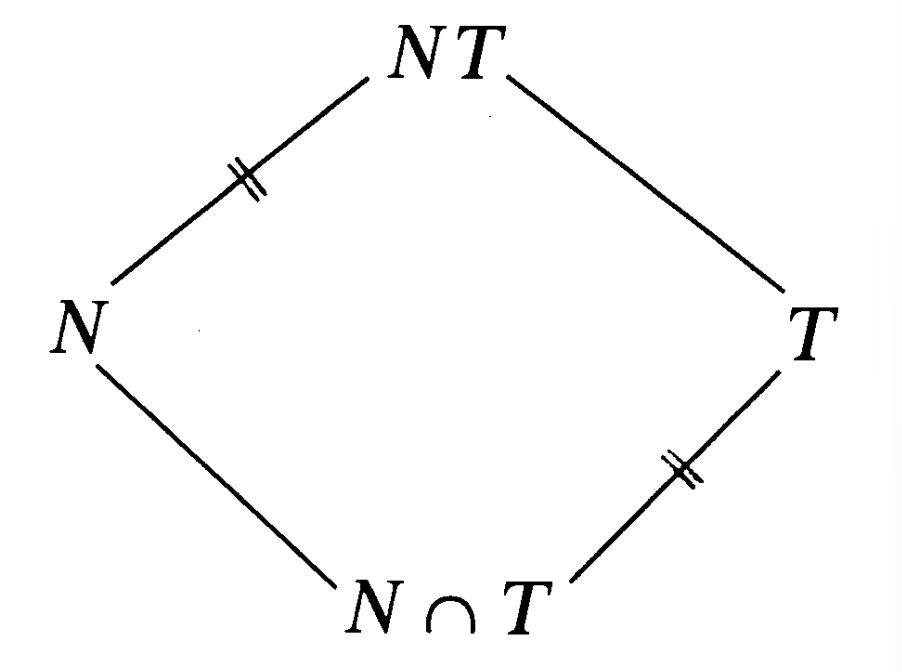

Theorem 2.6.4 (Second Isomorphism Theorem) Let and be subgroups of with normal. Then is normal in and .

Remark The following diagram is a mnemonic for this theorem:

Proof

Let be the natural map, and let , the restriction of to . Since is a homomorphism whose kernel is , Theorem 2.6.1 gives and . However, is just the family of all those cosets of having a representative in ; that is, consists of all the cosets in .

■

Theorem 2.6.5 (Third Isomorphism Theorem) Let , where both and are normal subgroups of . Then is a normal subgroup of and .

Proof

Define by (this "enlargement of coset" map is well defined because ). Then it is easily observed that is a surjective homomorphism with kernel . By Theorem 2.6.1 we have .

■

Proposition 2.6.6 (Modular Law) Let and be subgroups of with . If and , then .

Proposition 2.6.7 (Dedekind Law) Let and be subgroups of with . Then .

Proposition 2.6.8 Let be a homomorphism and let be a subgroup of . Then is a subgroup of containing .

Correspondence Theorem

Let and be sets. A function induces a "forward motion" and a "backward motion" between subsets of and subsets of . The forward motion assigns to each subset the subset of ; the backward motion assigns to each subset of the subset of . Morerover, if is a surjection, these motions define a bijection between all the subsets of and certain subsets of .

Theorem 2.7.1 (Correspondence Theorem) Let and let be the natural map. Then is a bijection from the family of all those subgroups of which contain to the family of all the subgroups of .

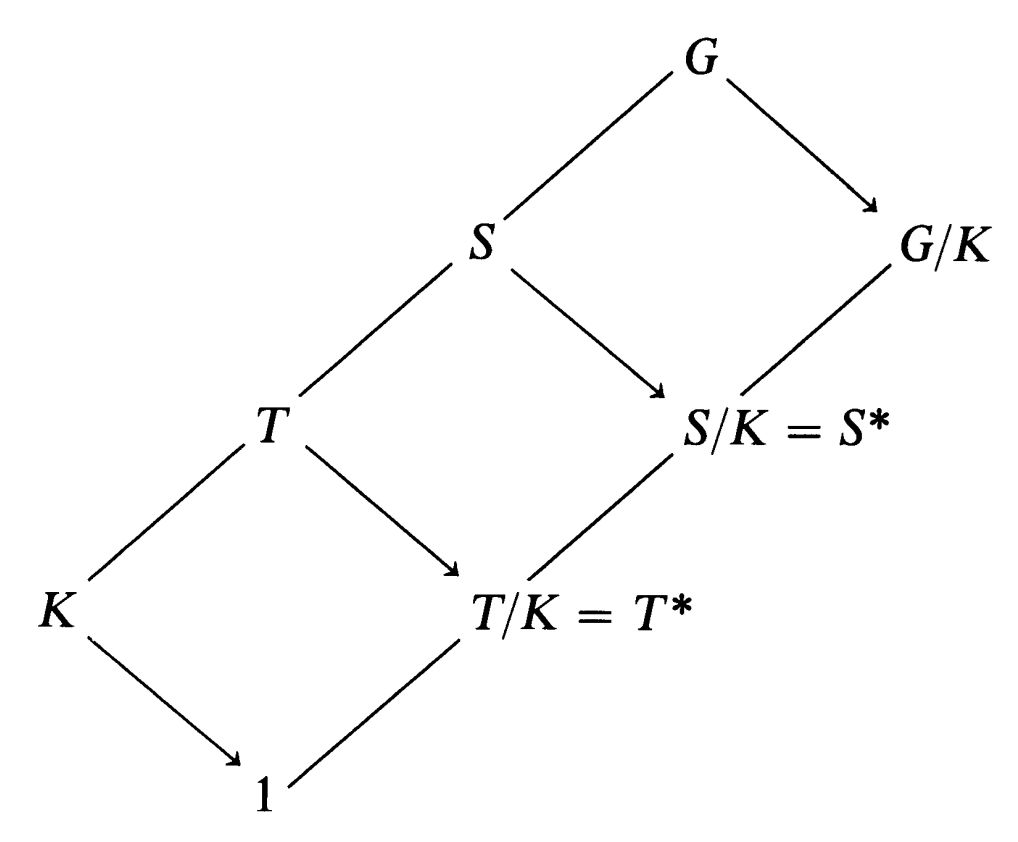

Moreover, if we denote by , then:

- if and only if , and then ;

- if and only if , and then .

Remark The following diagram is a mnemonic for this theorem:

Proof

We show first that is an injection: if and are subgroups containing , and if , then . To see this, let ; since , there exists with . Hence, for some and . The reverse inclusion is proved similarly. To see that the correspondence is a surjection, we must show that if , then there is a subgroup of containing with . By Proposition 2.6.8 is a subgroup of containing ; moreover, that is a surjection implies that .

It is plain that if , then . To prove that , it suffices to show that there is a bijection from the family of all cosets of the form , where , to the family of all cosets , where . It is easy to check that , defined by , is such a bijection.

If , then the third isomorphism theorem gives and ; that is, and . It remains to show that if , then . However, it is easily verified that , where and is the natural map.

■

Proposition 2.7.2 If , where is the commutator subgroup of , then and is abelian.

Definition 2.7.3 A group is simple if it has no normal subgroups other than and .

Proposition 2.7.4 A subgroup is a maximal subgroup of if there is no subgroup of with . If is a maximal subgroup, then is finite and equal to a prime.

Proposition 2.7.5 A subgroup is a maximal normal subgroup of if there is no normal subgroup of with . Then is a maximal normal subgroup of if and only if is simple.

Proposition 2.7.6 (Schur) Let be a homomorphism that does not send every element of into . If is simple, then must be an injection.

Direct Products

Definition 2.8.1 If and are groups, then their direct product, denoted by , is the group with elements all ordered pairs , where and , and with operation

It is easy to check that is a group: the identity is ; the inverse is . Notice that neigher nor is a subgroup of , but does contain isomorphic replicas of each, namely, and .

Theorem 2.8.2 Let be a group with normal subgroups and . If and , then .

Proof

If , then for some and (because ). We claim that and are uniquely determined by . If for and , then and ; hence and .

Define by , where . If and , then which is not in the proper form for evaluating . However, we could consider the commutator . Now for , and, similarly, ; therefore, and and commute. Now it is easily observed that is a homomorphism and a bijection; that is, is an isomorphism.

■

Theorem 2.8.3 If and , then and

Proof

The homomorphism , defined by , is surjective and . The first isomorphism theorem now gives the result.

■

Corollary 2.8.4 If , then .

There are two versions of the direct product : the external version, whose elements are ordered pairs and which contains isomorphic copies of and (namely, and ); the internal version which does contain and as normal subgroups and in which and . By Theorem 2.8.2, the two versions are isomorphic. In the future, we shall not distinguish between external and internal; in almost all cases, however, our point of view is internal. For example, we shall write Corollary 2.8.4 as .

Proposition 2.8.5 The operation of direct product is commutative and associative in the following sense: for groups and , we have

This means that the notations and are unambiguous.

Proposition 2.8.6 Let be a group having normal subgroups .

- If and, for all , , then .

- If each has a unique expression of the form , where each , then .

Proposition 2.8.7 Let be normal subgroups of a group , and define by , then we have

- ;

- if each has finite index in and if for all , then is a surjection and

Chapter III. Symmetric Groups and -Sets

Conjugates

Lemma 3.1.1 If is a group, then the relation " is a conjugate of in ," that is, for some , is an equivalence relation.

Definition 3.1.2 If is a group, then the equivalence class of under the relation " is a conjugate of in " is called the conjugacy class of ; it is denoted by .

If and are conjugate in , say, , then there is an isomorphism , namely, conjugation by , with . It follows that all the elements in the same conjugacy class have the same order.

If is the sole resident of its conjugacy class, then for all ; that is, commutes with every element of .

Definition 3.1.3 The center of a group , denoted by , is the set of all that commute with every element of .

It is easy to check that is a normal abelian subgroup of .

Definition 3.1.4 If , then the centralizer of in , denoted by , is the set of all which commute with .

It is easy to check that is a subgroup of .

Theorem 3.1.5 If , the number of conjugates of is equal to the index of its centralizer:

and this number is a divisor of when is finite.

Proof

Denote the family of all left cosets of in by , and define by . Now is well defined: if for some , then and commutes with ; that is, , and so . The function is an injection: if for some , then , commutes with , , and ; the function is a surjection: if , then . Therefore, is a bijection and . When is finite, Lagrange's theorem applies.

■

Definition 3.1.6 If and , then the conjugate is . The conjugate is often denoted by .

The conjugate is a subgroup of isomorphic to : if is conjugation by , then is an isomorphism from to .

Note that a subgroup is a normal subgroup if and only if it has only one conjugate.

Definition 3.1.7 If , then the normalizer of in , denoted by , is

It is immediate that is a subgroup of . Notice that ; indeed, is the largest subgroup of in which is normal.

Theorem 3.1.8 If , then the number of conjugates of in is equal to the index of its normalizer: , and divides when is finite. Moreover, if and only if .

Proof

Let denote the family of all the conjugates of , and let denote the family of all left cosets of in . Define by . Now is well defined: if for some , then and normalizes ; that is, , and so . The function is an injection: if for some , then , normalizes , , and ; the function is a surjection: if , then . Therefore, is a bijection and . When is finite, Lagrange's theorem applies.

■

Proposition 3.1.9 Let be a subgroup of , and , then we have

- ; that is, ;

- If , then .

- If , then .

Definition 3.1.10 If is a subset of , then the centralizer of in , denoted by , is the set of all which commute with any element in ; that is, .

Proposition 3.1.11 Let be a subset of , then we have

- is a subgroup of ; that is, ;

- when .

Proposition 3.1.12 If , then .

Remark When is an infinite subgroup, there may exist such that .

Proposition 3.1.13 If is a proper subgroup of a finite group , then is not the union of all the conjugates of .

Proposition 3.1.14 If is a finite group with conjugacy classes , and if , then .

Proposition 3.1.15 Let be a finite group, let be a normal subgroup of prime index, and let satisfy . If is conjugate to in , then is conjugate to in .

Definition 3.1.16 Let be a group. If , we call centerless.

Proposition 3.1.17 If , then is centerless.

Proposition 3.1.18 If is an -cycle, then its centralizer is .

Proposition 3.1.19

- Let be a group. If is not abelian, then is not cyclic.

- If is a group with , then is centerless.

- If and , then .

Symmetric Group

Definition 3.2.1 Two permutations have the same cycle structure if their complete factorizations into disjoint cycles have the same number of -cycles for each .

Lemma 3.2.2 If , then is the permutation with the same cycle structure as which is obtained by applying to the symbols in .

Proof

Let be the permutation defined in the lemma. If fixes a symbol , then fixes , for resides in a -cycle; but , and so fixes as well. Assume that moves ; say, . Let the complete factorization of be

If and , then . But , and so . Therefore, and agree on all symbols of the form ; since is a surjection, it follows that .

■

Theorem 3.2.3 Permutations are conjugate if and only if they have the same cycle structure.

Proof

The lemma shows that conjugate permutations do have the same cycle structure. For the converse, define as follows: place the complete factorization of over that of so that cycles of the same length correspond, and let be the function sending the top to the bottom. For example, if

then , etc. Notice that is a permutation, for every between and occurs exactly once in a complete factorization. The lemma gives , and so and are conjugate.

■

Corollary 3.2.4 A subgroup of is a normal subgroup if and only if, whenever , then every having the same cycle structure as also lies in .

Definition 3.2.5 If is a positive integer, then a partition of is a sequence of integers with .

Proposition 3.2.6 The number of conjugacy classes in is the number of partitions of .

The Simplicity of Alternating Groups

Lemma 3.3.1 is simple.

Proof

(i). All -cycles are conjugate in .

If, for example, , then the odd permutation commutes with . Since has index in , it is a normal subgroup of prime index, and so Proposition 3.1.15 says that has the same number of conjugates in as it does in because .(ii). All products of distinct transpositions are conjugate in .

If, for example, , then the odd permutation commutes with . Since has index in , Proposition 3.1.15 says that has the same number of conjugates in as it does in .(iii). There are two conjugacy classes of -cycles in , each of which has elements.

In , has conjugates, so that has elements; these must be the powers of . By Proposition 3.1.18, has order , hence, index .We have now surveyed all the conjugacy classes occuring in . Since every normal subgroup is a union of conjugacy classes, is a sum of and certain of the numbers: , , , and . It is easily checked that no such sum is a proper divisor of , so that and is simple.

■

Lemma 3.3.2 Let , where . If contains a -cycle, then .

Proof

We show that and are conjugate in (and thus that all -cycles are conjugate in ). If these cycles are not disjoint, then each fixes all the symbols outside of , say, and the two -cycles lie in , the group of all even permutations on these symbols. Of course, , and, as in part (i) of the previous proof, and are conjugate in ; a fortiori, they are conjugate in . If the cycles are disjoint, then we have just seen that is conjugate to and that is conjugate to , so that is conjugate to in this case as well.

A normal subgroup containing a -cycle must contain every conjugate of ; as all -cycles are conjugate, contains every -cycle. But Proposition 2.1.20 shows that is generated by the -cycles, and so .

■

Lemma 3.3.3 is simple.

Proof

Let be a normal subgroup of , and let be distinct from . If fixes some , define

Now and . But , by the second isomorphism theorem, so that simple and give ; that is, . Therefore, contains a -cycle, (by the lemma), and we are done.

We may now assume that no with fixes any , for . It could be easily shown that the cycle structure of is either or . In the first case, , and fixes (and ), a contradiction. In the second case, contains , where , and it is easily checked that this element is not the identity and it fixes , a contradiction. Therefore, no such normal subgroup can exist.

■

Theorem 3.3.4 is simple for all .

Proof

Let and let be a normal subgroup of . If and , then there is an with . If is a -cycle fixing and moving , then and do not commute: and ; therefore, their commutator is not the identity. Furthermore, lies in the normal subgroup , and, by Lemma 3.2.2, it is a product of two -cycles ; thus it moves at most symbols, say, . If , then and . Since is simple, and . Therefore contains a -cycle, (Lemma 3.3.2), and the proof is complete.

■

Proposition 3.3.5 If , then is the only proper nontrivial normal subgroup of .

Proposition 3.3.6 If is the set of all positive integers, then the infinite alternating group is the subgroup of generated by all the -cycles, and we have that is an infinite simple group.

Some Representation Theorems

Theorem 3.4.1 (Cayley) Every group can be imbedded as a subgroup of . In particular, if , then can be imbedded in .

Proof

Recall that for each , left translation , defined by , is a bijection; that is, . The theorem is proved if the function , given by is an injection and a homomorphism, for then . If , then , and so . Finally, we show that . If , then , while ; associativity shows that these are the same.

■

Definition 3.4.2 The homomorphism , given by , is called the left regular representation of .

Corollary 3.4.3 If is a field and is a finite group of order , then can be imbedded in .

Proof

The group of all permutation matrices is a subgroup of that is isomorphic to . Now apply Cayley's theorem to imbed into .

■

Theorem 3.4.4 If and , then there is a homomorphism with .

Proof

If and is the family of all the left cosets of in , define a function by for all . It is easy to check that each is a permutation of (its inverse is ) and that is a homomorphism . If , then for all ; in particular, , and so ; therefore, .

■

Definition 3.4.5 The homomorphism in Theorem 3.4.4 is called the representation of on the cosets of .

Corollary 3.4.6 A simple group which contains a subgroup of index can be imbedded in .

Proof

There is a homomorphism with . Since is simple, , and so is an injection.

■

Theorem 3.4.7 Let and let be the family of all the conjugates of in . There is a homomorphism with .

Proof

If , define by . If , then

We conclude that has inverse , so that and is a homomorphism.

If , then for all . In particular, , and so ; hence .

■

Definition 3.4.8 The homomorphism in Theorem 3.4.7 is called the representation of on the conjugates of .

Proposition 3.4.9 If is the representation of a group on the cosets of a subgroup , then .

Proposition 3.4.10 If is the representation of a group on the conjugates of a subgroup , then .

Proposition 3.4.11 Let , where is finite. If has conjugates and has conjugates, then .

Proposition 3.4.12 If and are subgroups of having finite index, then . Moreover, if , then .

Proposition 3.4.13 Let be an infinite simple group, then

- every with has infinitely many conjugates;

- every proper subgroup has infinitely many conjugates.

Proposition 3.4.14 If and are groups, then a homomorphism is a surjection if and only if it is right cancellable: for every group and every pair of homomorphisms , the equation implies .

Proposition 3.4.15 Let be a finite group containing a subgroup of index , where is the smallest prime divisor of . Then is a normal subgroup of .

-Sets

Definition 3.5.1 If is a set and is a group, then is a -set if there is a function (called an action), denoted by , such that:

- for all ;

- for all and .

One also says that acts on . If , then is called the degree of the -set .

Theorem 3.5.2 If is a -set with action , then there is a homomorphism given by . Conversely, every homomorphism defines an action, namely, , which makes into a -set.

Proof

If is a -set, , and , then

it follows that each is a permutation of with the inverse . That is a homomorphism is immediate from (ii) of the definition of -set. The converse is also routine.

■

If , define

If for all , then is called a symmetric function. If a polynomial has roots , then each of the coefficients of is a symmetric function of . Other interesting functions of the roots may not be symmetric. For example, the discriminant of is defined to be the numer , where . If , then it is easy to see, for every , that . Indeed, is an alternating function of the roots: if and only if .

Given , find

it is easy to see that ; moreover, is symmetric if and only if , while .

Definition 3.5.3 If is a -set and , then the -orbit of is

Usually, we will say orbit instead of -orbit. The orbits of form a partition; indeed, the relation defined by " for some " is an equivalence relation whose equivalence classes are the orbits.

Definition 3.5.4 If is a -set and , then the stabilizer of , denoted by , is the subgroup

Example 3.5.5 If acts on itself by conjugation and , then is the conjugacy class of and .

Example 3.5.6 If acts by conjugation on the family of all its subgroups and if , then and .

Theorem 3.5.7 If is a -set and , then

Proof

If , let denote the family of all left cosets of in . Define by . Now is well defined: if for some , then , , and . The function is an injection: if for some , then , , and ; the function is a surjection: if , then . Therefore, is a bijection and .

■

Corollary 3.5.8 If a finite group acts on a set , then the number of elements in any orbit is a divisor of .

Proposition 3.5.9 Let be a -set, let , and let for some . Then we have , and also .

Definition 3.5.10 A -set is transitive if it has only one orbit; that is, for every , there exists with .

Proposition 3.5.11 If is a -set, then each of its orbits is a transitive -set.

Proposition 3.5.12 If , then acts transitively on the set of all left cosets of , and acts transitively on the set of all conjugates of .

Proposition 3.5.13 Let be a -set with action , and let send into the permutation .

- If , then is a -set if one defines .

- If is a transitive -set, then is a transitive -set.

- If is a transitive -set, then .

Proposition 3.5.14 If , then acts on . In particular, acts on for every . If the complete factorization of into disjoint cycles is and if is a symbol appearing in , then consists of all the symbols appearing in .

Counting Orbits

Let us call a -set finite if both and are finite.

Theorem 3.6.1 (Burnside's Lemma) If is a finite -set and is the number of -orbits of , then

where, for , is the number of fixed by .

Proof

In the sum , each is counted times (for consists of all those which fix ). If and lie in the same orbit, then Proposition 3.5.9 gives , and so the elements constituting the orbit of are, in the above sum, collectively counted times. Each orbit thus contributes to the sum, and so .

■

Corollary 3.6.2 If is a finite transitive -set with , then there exists having no fixed points.

Proof

Since is transitive, the number of orbits of is , and so Burnside's lemma gives

Now ; if for every , then the right hand side is too large.

■

Definition 3.6.3 If , where , and if is a set of colors, then is a -set if we define for all . If , then an orbit of is called a -coloring of .

Lemma 3.6.4 Let be a set of colors, and let . If , then , where is the number of cycles occurring in the complete factorization of .

Proof

Since , we see that for all , and so has the same color as . It follows that has the same color as , for all ; that is, all in the -orbit of have the same color. But Proposition 3.5.14 shows that if the complete factorization of is , and if occurs in , then the set of symbols occuring in is the -orbit containing . Since there are orbits and colors, there are -tuples fixed by in its action on .

■

Definition 3.6.5 If the complete factorization of has -cycles, then the index of is

If , then the cycle index of is the polynomial

Corollary 3.6.6 If and , then the number of -colorings of is .

Proof

By Burnside's lemma for the -set , the number of -colorings of is

By Lemma 3.6.4, this number is

where is the number of cycles in the complete factorization of . On the other hand,

and so

■

Theorem 3.6.7 (Pólya) Let , where , let , and, for each , define . Then the number of -colorings of with elements of color , for every , is the coefficient of in .

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■

【推荐】国内首个AI IDE,深度理解中文开发场景,立即下载体验Trae

【推荐】编程新体验,更懂你的AI,立即体验豆包MarsCode编程助手

【推荐】抖音旗下AI助手豆包,你的智能百科全书,全免费不限次数

【推荐】轻量又高性能的 SSH 工具 IShell:AI 加持,快人一步

· 分享一个免费、快速、无限量使用的满血 DeepSeek R1 模型,支持深度思考和联网搜索!

· 基于 Docker 搭建 FRP 内网穿透开源项目(很简单哒)

· ollama系列1:轻松3步本地部署deepseek,普通电脑可用

· 按钮权限的设计及实现

· 【杂谈】分布式事务——高大上的无用知识?