mim

China, GitHub and the man-in-the-middle

What happened?

At around 8pm, on January 26, reports appeared on Weibo and Twitter that users in China trying to access GitHub.com were getting warning messages about invalid SSL certificates. The evidence, listed further down in this post, indicates that this was caused by a man-in-the-middle attack.

What is a man-in-the-middle-attack?

Wikipedia defines a man-in-the-middle-attack in the following way:

The man-in-the-middle attack...is a form of active eavesdropping in which the attacker makes independent connections with the victims and relays messages between them, making them believe that they are talking directly to each other over a private connection, when in fact the entire conversation is controlled by the attacker.

We go into detail about what happened later in this post, but first we will explore why we think this happened.

Why?

At the time of writing, there are 5,103,522 repositories of data on GitHub and as many possible theories as to why the Chinese authorities want to block or interfere with access. We will focus on one of these theories however please note that this is pure speculation on our part.

On January 25, the day before the man-in-the-middle attack, the following petition was created on WhiteHouse.gov:

The petition has gathered more than 8,000 signatures in the five days since. To make the idea specific, there is a link to a list of Chinese individuals accused of contributing to the technical infrastructure behind online censorship in China. And this list is hosted on - you guessed it - GitHub. The list has gathered hundreds of comments, the vast majority in Chinese. One of these comments contains the supposed address and ID number of Fang Binxing, the Principal of Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications and often called the “Father of China's Great Firewall”.

Another comment links to another much longer list of supposed contributors to the Great Firewall, also hosted on GitHub.

About a week prior to this event, GitHub was completely blocked in China. But only a couple of days later, full access to the website was restored. This followed unusually public protest that may have forced the authorities to rethink their decision. It’s clear that a lot of software developers in China rely on GitHub for their code sharing. Completely cutting access affects big business. GitHub may just be too important to block.

That leaves the authorities in a real pickle. They can’t selectively block content on GitHub nor monitor what users are doing there. They also cannot block the website altogether lest they hurt important Chinese companies. This is where man-in-the-middle attacks make their entrance. By faking SSL certificates, the authorities can indeed intercept and track traffic to encrypted websites.

The White House petition has not been blocked. But the GitHub lists are much more interesting because they allow users to freely comment and to collaborate on the content. Because all traffic to GitHub is encrypted, and because it seems that the authorities have backed off from blocking the website completely, the only tool left in the censorship toolbox is man-in-the-middle attacks.

The attack happened on a Saturday night. It was very crude, in that the fake certificate was signed by an unknown authority and bound to be detected quickly. The attack stopped after about an hour. The whole episode seems rather irrational. It’s conceivable that one or several individuals identified on these lists as enemies of a free Internet decided to take action into their own hands. They are the technical people behind the Great Firewall and so they would clearly be capable of implementing this attack. They had a motive in that they were personally being targeted by the people behind the White House petition. And they had no other options since they had been barred from blocking GitHub completely.

While the attack was short-lived, it is possible that passwords of many GitHub users were recorded. It’s also possible that the IP addresses of users accessing certain URLs, such as these lists of GFW contributors, were tracked. The people organizing these initiatives should take great care.

The lists are alive and well. Regardless of whether the White House petition garners the 100,000 signatures necessary to warrant an official response, this is a clear sign of increased pressure on technical people helping the government to censor the Internet. The increasing public anger over censorship and organized efforts such as this one to name and shame collaborators could make it more difficult for the authorities to recruit and maintain talent in the future.

Has it happened before?

This Fat Duck blog post describes a man-in-middle attack on the Skype login page in 2011. Unlike this latest attack, the host appears to have been DNS poisoned at that time. If anything, it was an even more obvious attack, since the IP address returned was supposedly publicly registered by the Public Security Bureau. This surveillence may appear unnecessary since Skype is collaborating with Tom Online for their Chinese users and all data sent through the Tom version is already tracked. If you register and login directly through https://login.skype.com, however, you are accessing the regular Skype version hosted outside of China. It may have been an attempt to compromise users who are not using the Tom Online version of Skype.

Man-in-the-middle attacks have also been deployed in Syria to track activity, presumingly by activists, on Facebook.

Will it happen again?

GitHub is an HTTPS-only website. That means that all communication is encrypted by default. Only the end user and the GitHub server knows what information is being uploaded and downloaded. The Great Firewall, through which all traffic going out of China passes, can only know that the user is accessing data on GitHub’s servers - not what that data is. This in turn means that the authorities cannot block individual pages on GitHub - all they can do is to block the website altogether.

HTTPS effectively disables half of what the Great Firewall can do. We have argued for a long time that the reason that Gmail isn’t fully blocked is that it’s considered too important and that the backlash against closing down access would be too great. The same thing applies to the Apple App Store. It now appears that GitHub has been added to this list. Other major websites that could follow suit include Google Search and Wikipedia. With every website that switches to HTTPS, the authorities’ options are limited to two: completely blocking it, or completely allowing it. The more they fear a public reaction to complete blocks, the fewer their options become. Man-in-the-middle attacks are likely to become increasingly tempting.

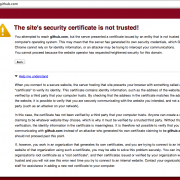

As we show in the overview of browsers popular in China, further down in this post, even an invalid SSL certificate is likely to be accepted by a lot of users since the warnings are weak. If man-in-the-middle attacks become more widespread though, more users will likely learn how to understand these messages and hopefully also switch to safer browsers such as Google Chrome and Firefox.

No browser would prevent the authorities from using their ultimate tool though: certificates signed by the China Internet Network Information Center. CNNIC is controlled by the government through the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. They are recognized by all major browsers as a trusted Certificate Authority. If they sign a fake certificate used in a man-in-the-middle attack, no browser will warn of any usual activity.

Such an attack on Gmail, for example, could mean that you would sign in to Gmail as usual and receive no warning*. However, your password and all your activity could be recorded by the authorities.

Update: Google Chrome would actually warn you, even block access, if you tried to use Gmail and received a certificate signed by a different CA. This applies to a lot of Google sites as well as other websites that "have requested it". The technique is called Public key pinning. Thanks to N.S. (see comment top-right) for the info.

The attack would be detectable by manually reviewing the SSL certificate. While the vast majority of users would not do this, one single report on such an attack would create a huge international scandal that might lead to major browsers removing their trust of CNNIC. So the authorities will likely avoid using this tool, unless they feel it’s absolutely necessary.

At the same time, completely excluding CNNIC would be a further step in isolating China from the global Internet and toward the creation of a separate Chinanet. China is too big to exclude. The international security community is simply hoping that CNNIC will behave. Chinese activists depending on the encryption offered by Gmail and now also GitHub share that hope.

If hope isn’t your thing, you can manually remove CNNIC certificates in your browser or operating system. Lost Laowai has an instructive post on how to do this. At GreatFire.org we are not big fans of trusting Chinese authorities to behave either. Our automatic censorship tests currently do not include recording and validating SSL certificates, but we will work hard to include such functionality as soon as possible.

Evidence of attack

We do not have data ourselves to show how or if this happened. We rely on the sources listed below. Many of these sources were used in this report on Solidot. That GitHub would be targeted is also supported by the fact that the site was completely blocked in China only a few days earlier.

GitHub was not subject to DNS poisoning at the time. Our own tests (of github.com as well as the https version) conducted on the same day all show the same IP address as when accessed from the US, as does the Wireshark capture file listed below. That means that the traffic must have been interfered with somewhere between end users and the GitHub server. Users were apparently communicating with the GitHub IP address, but the traffic was altered along the way and the SSL certificate sent to the user was clearly different.

For further reading, check out this discussion on YCombinator.

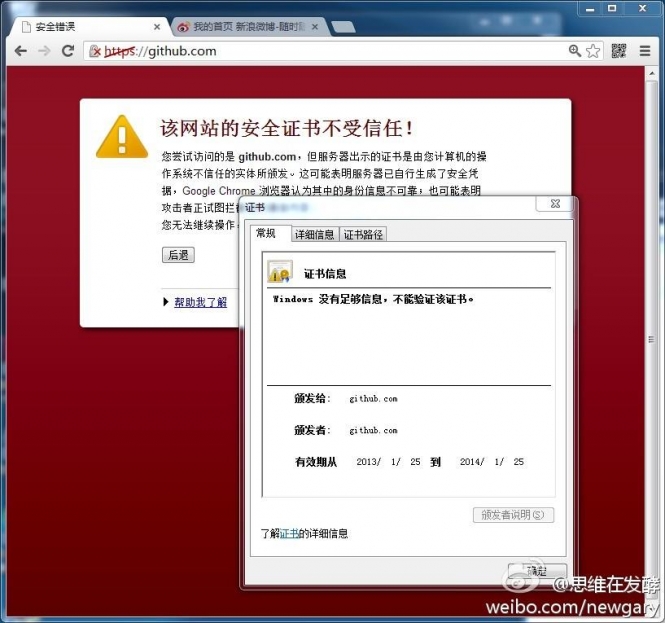

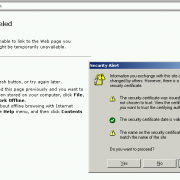

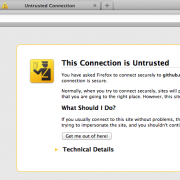

1. Screenshot taken by Weibo user

The screenshot shows the user trying to access GitHub using the Chrome browser and receiving a warning about an invalid SSL certificate.

2. Wireshark capture file

Uploaded by unknown user to CloudShark. Copy hosted by us.

3. Reports on Twitter

- https://twitter.com/chenshaoju/status/295139636718743552

- https://twitter.com/xierch/status/295152185052901376

4. Copy of fake SSL certificate

Uploaded by unknown user to MediaFire. Copy hosted by us. See below for a comparison of the current valid certificate and the fake one used during the attack.

| The Current GitHub.com SSL Certificate | The Fake GitHub.com SSL Certificate |

|---|---|

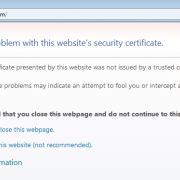

Does your browser protect you?

Man-in-the-middle attacks are not a new phenomenon. Browser providers have created features to combat them for years. This particular attack was very crude - the fake SSL certificate was not signed by a known certificate authority. Virtually all browsers would produce some sort of error, as can be seen in the screenshots above. For a full overview, we have recreated a GitHub mirror website at https://github.greatfire.org using a certificate formatted in the same way as the one used in the attack. You can visit it to get an idea of the kind of warning that would have been shown during the attack.

For an even more accurate experience, add the following to your hosts file and then browse to https://github.com.

54.235.205.92 github.com

Using the above method, we’ve taken screenshots of the warning messages shown to users in some of the most popular browsers in China as well as Chrome and Firefox which are used by a small minority but are considerably safer.

All browsers display some sort of warning. If you are in a hurry and you do not know of the risk of a man-in-the-middle attack you will likely click “continue”. If your browser is either 360 Safe Browser or Internet Explorer 6, which together make up for about half of all browsers used in China, all you need to do is to click continue once. You will see no subsequent warnings. 360’s so-called “Safe Browser” even shows a green check suggesting that the website is safe, once you’ve approved the initial warning message.

Chrome and Firefox have the highest level of security. As long as you have visited GitHub at least once prior to the attack, they won’t allow you to make security exceptions at all. The risk, of course, is that the user will then just switch to another browser in order to get their work done.

| First visit | Subsequent use | |

|---|---|---|

| 360 Safe Browser (27% market share) |

Warning. One click to continue. |

No warnings. Green check suggesting that the certificate is valid. |

| IE6 (22%) |

Warning. One click to continue. |

No warnings. |

| IE8 (21%) | Not tested. | Not tested. |

| IE9 (5%) |

Warning. One click to continue. |

“Certificate error” warning in location bar. |

| Safari (3%) |

Warning. One click to continue. |

No warnings. Lock suggesting that the certificate is valid. What’s more, even clicking the lock will display a misleading encryption channel message. |

| Chrome (2%) |

Warning. Impossible to add exception, if you have visited GitHub before with a valid certificate. “You cannot proceed because the website operator has requested heightened security for this domain”. This is because of HSTS. |

Impossible if HSTS was enabled. Otherwise possible. |

| Firefox (1%) |

Same as Chrome. If you have not visited GitHub prior to the attack, possible to create a security exception, but many clicks necessary to continue. |

Same as Chrome. |

【推荐】国内首个AI IDE,深度理解中文开发场景,立即下载体验Trae

【推荐】编程新体验,更懂你的AI,立即体验豆包MarsCode编程助手

【推荐】抖音旗下AI助手豆包,你的智能百科全书,全免费不限次数

【推荐】轻量又高性能的 SSH 工具 IShell:AI 加持,快人一步

· AI与.NET技术实操系列(二):开始使用ML.NET

· 记一次.NET内存居高不下排查解决与启示

· 探究高空视频全景AR技术的实现原理

· 理解Rust引用及其生命周期标识(上)

· 浏览器原生「磁吸」效果!Anchor Positioning 锚点定位神器解析

· DeepSeek 开源周回顾「GitHub 热点速览」

· 物流快递公司核心技术能力-地址解析分单基础技术分享

· .NET 10首个预览版发布:重大改进与新特性概览!

· AI与.NET技术实操系列(二):开始使用ML.NET

· 单线程的Redis速度为什么快?

2019-04-02 Kafka分区分配策略(Partition Assignment Strategy

2018-04-02 go语言通道详解

2018-04-02 使用Spring Cloud连接不同服务

2018-04-02 并发之痛 Thread,Goroutine,Actor

2015-04-02 在Sqlite中通过Replace来实现插入和更新