www的原始提案(1989年)

W3 项目(当时这个项目叫w3)资料主要来自:

| 放在w3c站点的原始提案 | https://w3c.org/History/1989/proposal.html |

| https://home.cern/science/computing/birth-web | |

| 万维网:超文本项目提案 | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/Proposal.html |

| 项目历史的总结 | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/History.html |

| 相对整体介绍这个项目(项目背景) | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html |

| 相关这个项目的技术细节 | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/Technical.html |

| 此页面仅用于历史兴趣;内容自 1992 年底以来未更新(w3 server) | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/DataSources/WWW/Servers.html |

| 万维网分布式代码 | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/README.html |

| 以下列出了 W3 倡议和相关事项的论文和文章 | http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/Bibliography.html |

| CERN 的互联网史前史 | https://home.cern/news/opinion/computing/internet-prehistory-cern |

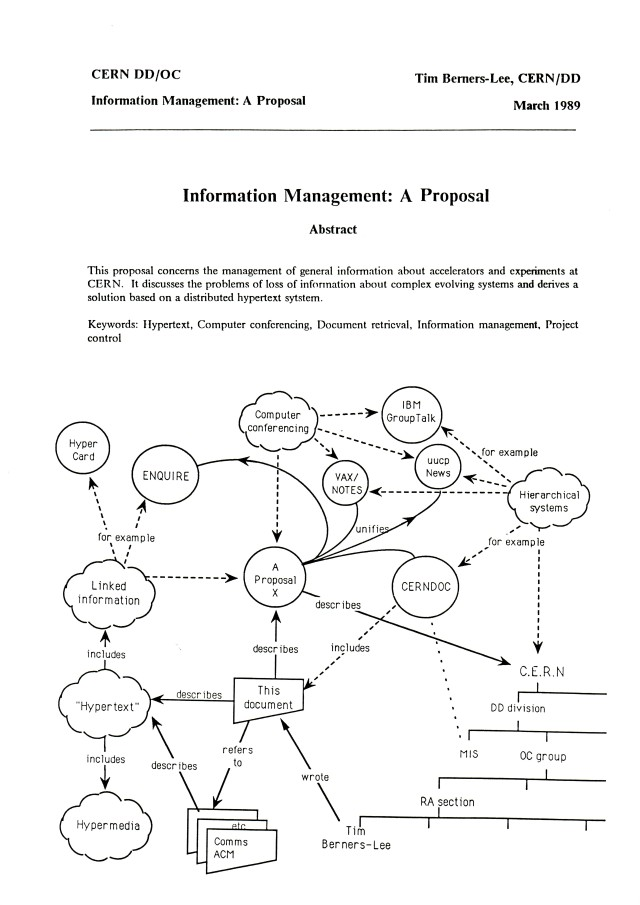

A hand conversion to HTML of the original MacWord (or Word for Mac?) document written in March 1989 and later redistributed unchanged apart from the date added in May 1990. Provided for historical interest only. The diagrams are a bit dotty, but available in versioins linked below. The text has not been changed, even to correct errors such as misnumbered figures or unfinished references.

This document was an attempt to persuade CERN management that a global hypertext system was in CERN's interests. Note that the only name I had for it at this time was "Mesh" -- I decided on "World Wide Web" when writing the code in 1990.

Other versions which are available are:

- The original document file (I think - I can't test it)

- The RTF file generated from the above, with scalable drawings

- A Microsoft style HTML file generated from the RTF file by MSword in 1998, with pixely versions of the drawings

©Tim Berners-Lee 1989, 1990, 1996, 1998. All rights reserved.

Information Management: A Proposal

Tim Berners-Lee, CERNMarch 1989, May 1990

This proposal concerns the management of general information about accelerators and experiments at CERN. It discusses the problems of loss of information about complex evolving systems and derives a solution based on a distributed hypertext system.

Overview

Many of the discussions of the future at CERN and the LHC era end with the question - ªYes, but how will we ever keep track of such a large project?º This proposal provides an answer to such questions. Firstly, it discusses the problem of information access at CERN. Then, it introduces the idea of linked information systems, and compares them with less flexible ways of finding information.

It then summarises my short experience with non-linear text systems known as ªhypertextº, describes what CERN needs from such a system, and what industry may provide. Finally, it suggests steps we should take to involve ourselves with hypertext now, so that individually and collectively we may understand what we are creating.

Losing Information at CERN

CERN is a wonderful organisation. It involves several thousand people, many of them very creative, all working toward common goals. Although they are nominally organised into a hierarchical management structure,this does not constrain the way people will communicate, and share information, equipment and software across groups.

The actual observed working structure of the organisation is a multiply connected "web" whose interconnections evolve with time. In this environment, a new person arriving, or someone taking on a new task, is normally given a few hints as to who would be useful people to talk to. Information about what facilities exist and how to find out about them travels in the corridor gossip and occasional newsletters, and the details about what is required to be done spread in a similar way. All things considered, the result is remarkably successful, despite occasional misunderstandings and duplicated effort.

A problem, however, is the high turnover of people. When two years is a typical length of stay, information is constantly being lost. The introduction of the new people demands a fair amount of their time and that of others before they have any idea of what goes on. The technical details of past projects are sometimes lost forever, or only recovered after a detective investigation in an emergency. Often, the information has been recorded, it just cannot be found.

If a CERN experiment were a static once-only development, all the information could be written in a big book. As it is, CERN is constantly changing as new ideas are produced, as new technology becomes available, and in order to get around unforeseen technical problems. When a change is necessary, it normally affects only a small part of the organisation. A local reason arises for changing a part of the experiment or detector. At this point, one has to dig around to find out what other parts and people will be affected. Keeping a book up to date becomes impractical, and the structure of the book needs to be constantly revised.

The sort of information we are discussing answers, for example, questions like

- Where is this module used?

- Who wrote this code? Where does he work?

- What documents exist about that concept?

- Which laboratories are included in that project?

- Which systems depend on this device?

- What documents refer to this one?

The problems of information loss may be particularly acute at CERN, but in this case (as in certain others), CERN is a model in miniature of the rest of world in a few years time. CERN meets now some problems which the rest of the world will have to face soon. In 10 years, there may be many commercial solutions to the problems above, while today we need something to allow us to continue.

Linked information systems

In providing a system for manipulating this sort of information, the hope would be to allow a pool of information to develop which could grow and evolve with the organisation and the projects it describes. For this to be possible, the method of storage must not place its own restraints on the information. This is why a "web" of notes with links (like references) between them is far more useful than a fixed hierarchical system. When describing a complex system, many people resort to diagrams with circles and arrows. Circles and arrows leave one free to describe the interrelationships between things in a way that tables, for example, do not. The system we need is like a diagram of circles and arrows, where circles and arrows can stand for anything.

We can call the circles nodes, and the arrows links. Suppose each node is like a small note, summary article, or comment. I'm not over concerned here with whether it has text or graphics or both. Ideally, it represents or describes one particular person or object. Examples of nodes can be

- People

- Software modules

- Groups of people

- Projects

- Concepts

- Documents

- Types of hardware

- Specific hardware objects

The arrows which links circle A to circle B can mean, for example, that A...

- depends on B

- is part of B

- made B

- refers to B

- uses B

- is an example of B

These circles and arrows, nodes and links, have different significance in various sorts of conventional diagrams:

| Diagram | Nodes are | Arrows mean |

|---|---|---|

| Family tree | People | "Is parent of" |

| Dataflow diagram | Software modules" | Passes data to" |

| Dependency | Module | "Depends on" |

| PERT chart | Tasks | "Must be done before" |

| Organisational chart | People | "Reports to" |

The system must allow any sort of information to be entered. Another person must be able to find the information, sometimes without knowing what he is looking for.

In practice, it is useful for the system to be aware of the generic types of the links between items (dependences, for example), and the types of nodes (people, things, documents..) without imposing any limitations.

The problem with trees

Many systems are organised hierarchically. The CERNDOC documentation system is an example, as is the Unix file system, and the VMS/HELP system. A tree has the practical advantage of giving every node a unique name. However, it does not allow the system to model the real world. For example, in a hierarchical HELP system such as VMS/HELP, one often gets to a leaf on a tree such as

HELP COMPILER SOURCE_FORMAT PRAGMAS DEFAULTS

only to find a reference to another leaf: "Please see

HELP COMPILER COMMAND OPTIONS DEFAULTS PRAGMAS"

and it is necessary to leave the system and re-enter it. What was needed was a link from one node to another, because in this case the information was not naturally organised into a tree.

Another example of a tree-structured system is the uucp News system (try 'rn' under Unix). This is a hierarchical system of discussions ("newsgroups") each containing articles contributed by many people. It is a very useful method of pooling expertise, but suffers from the inflexibility of a tree. Typically, a discussion under one newsgroup will develop into a different topic, at which point it ought to be in a different part of the tree. (See Fig 1).

From mcvax!uunet!pyrdc!pyrnj!rutgers!bellcore!geppetto!duncan Thu Mar...

Article 93 of alt.hypertext:

Path: cernvax!mcvax!uunet!pyrdc!pyrnj!rutgers!bellcore!geppetto!duncan

>From: duncan@geppetto.ctt.bellcore.com (Scott Duncan)

Newsgroups: alt.hypertext

Subject: Re: Threat to free information networks

Message-ID: <14646@bellcore.bellcore.com>

Date: 10 Mar 89 21:00:44 GMT

References: <1784.2416BB47@isishq.FIDONET.ORG> <3437@uhccux.uhcc...

Sender: news@bellcore.bellcore.com

Reply-To: duncan@ctt.bellcore.com (Scott Duncan)

Organization: Computer Technology Transfer, Bellcore

Lines: 18

Doug Thompson has written what I felt was a thoughtful article on

censorship -- my acceptance or rejection of its points is not

particularly germane to this posting, however.

In reply Greg Lee has somewhat tersely objected.

My question (and reason for this posting) is to ask where we might

logically take this subject for more discussion. Somehow alt.hypertext

does not seem to be the proper place.

Would people feel it appropriate to move to alt.individualism or even

one of the soc groups. I am not so much concerned with the specific

issue of censorship of rec.humor.funny, but the views presented in

Greg's article.

Speaking only for myself, of course, I am...

Scott P. Duncan (duncan@ctt.bellcore.com OR ...!bellcore!ctt!duncan)

(Bellcore, 444 Hoes Lane RRC 1H-210, Piscataway, NJ...)

(201-699-3910 (w) 201-463-3683 (h))

|

The Subject field allows notes on the same topic to be linked together within a "newsgroup". The name of the newsgroup (alt.hypertext) is a hierarchical name. This particular note is expresses a problem with the strict tree structure of the scheme: this discussion is related to several areas. Note that the "References", "From" and "Subject" fields can all be used to generate links.

The problem with keywords

Keywords are a common method of accessing data for which one does not have the exact coordinates. The usual problem with keywords, however, is that two people never chose the same keywords. The keywords then become useful only to people who already know the application well.

Practical keyword systems (such as that of VAX/NOTES for example) require keywords to be registered. This is already a step in the right direction. A linked system takes this to the next logical step. Keywords can be nodes which stand for a concept. A keyword node is then no different from any other node. One can link documents, etc., to keywords. One can then find keywords by finding any node to which they are related. In this way, documents on similar topics are indirectly linked, through their key concepts. A keyword search then becomes a search starting from a small number of named nodes, and finding nodes which are close to all of them.

It was for these reasons that I first made a small linked information system, not realising that a term had already been coined for the idea: "hypertext".

A solution: Hypertext

Personal Experience with Hypertext

In 1980, I wrote a program for keeping track of software with which I was involved in the PS control system. Called Enquire, it allowed one to store snippets of information, and to link related pieces together in any way. To find information, one progressed via the links from one sheet to another, rather like in the old computer game "adventure". I used this for my personal record of people and modules. It was similar to the application Hypercard produced more recently by Apple for the Macintosh. A difference was that Enquire, although lacking the fancy graphics, ran on a multiuser system, and allowed many people to access the same data.

Documentation of the RPC project (concept)

Most of the documentation is available on VMS, with the two

principle manuals being stored in the CERNDOC system.

1) includes: The VAX/NOTES conference VXCERN::RPC

2) includes: Test and Example suite

3) includes: RPC BUG LISTS

4) includes: RPC System: Implementation Guide

Information for maintenance, porting, etc.

5) includes: Suggested Development Strategy for RPC Applications

6) includes: "Notes on RPC", Draft 1, 20 feb 86

7) includes: "Notes on Proposed RPC Development" 18 Feb 86

8) includes: RPC User Manual

How to build and run a distributed system.

9) includes: Draft Specifications and Implementation Notes

10) includes: The RPC HELP facility

11) describes: THE REMOTE PROCEDURE CALL PROJECT in DD/OC

Help Display Select Back Quit Mark Goto_mark Link Add Edit

|

This example is basically a list, so the list of links is more important than the text on the node itself. Note that each link has a type ("includes" for example) and may also have comment associated with it. (The bottom line is a menu bar.)

Soon after my re-arrival at CERN in the DD division, I found that the environment was similar to that in PS, and I missed Enquire. I therefore produced a version for the VMS, and have used it to keep track of projects, people, groups, experiments, software modules and hardware devices with which I have worked. I have found it personally very useful. I have made no effort to make it suitable for general consumption, but have found that a few people have successfully used it to browse through the projects and find out all sorts of things of their own accord.

Hot spots

Meanwhile, several programs have been made exploring these ideas, both commercially and academically. Most of them use "hot spots" in documents, like icons, or highlighted phrases, as sensitive areas. touching a hot spot with a mouse brings up the relevant information, or expands the text on the screen to include it. Imagine, then, the references in this document, all being associated with the network address of the thing to which they referred, so that while reading this document you could skip to them with a click of the mouse.

"Hypertext" is a term coined in the 1950s by Ted Nelson [...], which has become popular for these systems, although it is used to embrace two different ideas. One idea (which is relevant to this problem) is the concept: "Hypertext": Human-readable information linked together in an unconstrained way.

The other idea, which is independent and largely a question of technology and time, is of multimedia documents which include graphics, speech and video. I will not discuss this latter aspect further here, although I will use the word "Hypermedia" to indicate that one is not bound to text.

It has been difficult to assess the effect of a large hypermedia system on an organisation, often because these systems never had seriously large-scale use. For this reason, we require large amounts of existing information should be accessible using any new information management system.

CERN Requirements

To be a practical system in the CERN environment, there are a number of clear practical requirements.

Remote access across networks.

CERN is distributed, and access from remote machines is essential.

Heterogeneity

Access is required to the same data from different types of system (VM/CMS, Macintosh, VAX/VMS, Unix)

Non-Centralisation

Information systems start small and grow. They also start isolated and then merge. A new system must allow existing systems to be linked together without requiring any central control or coordination.

Access to existing data

If we provide access to existing databases as though they were in hypertext form, the system will get off the ground quicker. This is discussed further below.

Private links

One must be able to add one's own private links to and from public information. One must also be able to annotate links, as well as nodes, privately.

Bells and Whistles

Storage of ASCII text, and display on 24x80 screens, is in the short term sufficient, and essential. Addition of graphics would be an optional extra with very much less penetration for the moment.

Data analysis

An intriguing possibility, given a large hypertext database with typed links, is that it allows some degree of automatic analysis. It is possible to search, for example, for anomalies such as undocumented software or divisions which contain no people. It is possible to generate lists of people or devices for other purposes, such as mailing lists of people to be informed of changes. It is also possible to look at the topology of an organisation or a project, and draw conclusions about how it should be managed, and how it could evolve. This is particularly useful when the database becomes very large, and groups of projects, for example, so interwoven as to make it difficult to see the wood for the trees.

In a complex place like CERN, it's not always obvious how to divide people into groups. Imagine making a large three-dimensional model, with people represented by little spheres, and strings between people who have something in common at work.

Now imagine picking up the structure and shaking it, until you make some sense of the tangle: perhaps, you see tightly knit groups in some places, and in some places weak areas of communication spanned by only a few people. Perhaps a linked information system will allow us to see the real structure of the organisation in which we work.

Live links

The data to which a link (or a hot spot) refers may be very static, or it may be temporary. In many cases at CERN information about the state of systems is changing all the time. Hypertext allows documents to be linked into "live" data so that every time the link is followed, the information is retrieved. If one sacrifices portability, it is possible so make following a link fire up a special application, so that diagnostic programs, for example, could be linked directly into the maintenance guide.

Non requirements

Discussions on Hypertext have sometimes tackled the problem of copyright enforcement and data security. These are of secondary importance at CERN, where information exchange is still more important than secrecy. Authorisation and accounting systems for hypertext could conceivably be designed which are very sophisticated, but they are not proposed here.

In cases where reference must be made to data which is in fact protected, existing file protection systems should be sufficient.

Specific Applications

The following are three examples of specific places in which the proposed system would be immediately useful. There are many others.

Development Project Documentation.

The Remote procedure Call project has a skeleton description using Enquire. Although limited, it is very useful for recording who did what, where they are, what documents exist, etc. Also, one can keep track of users, and can easily append any extra little bits of information which come to hand and have nowhere else to be put. Cross-links to other projects, and to databases which contain information on people and documents would be very useful, and save duplication of information.

Document retrieval.

The CERNDOC system provides the mechanics of storing and printing documents. A linked system would allow one to browse through concepts, documents, systems and authors, also allowing references between documents to be stored. (Once a document had been found, the existing machinery could be invoked to print it or display it).

The "Personal Skills Inventory".

Personal skills and experience are just the sort of thing which need hypertext flexibility. People can be linked to projects they have worked on, which in turn can be linked to particular machines, programming languages, etc.

The State of the Art in Hypermedia

An increasing amount of work is being done into hypermedia research at universities and commercial research labs, and some commercial systems have resulted. There have been two conferences, Hypertext '87 and '88, and in Washington DC, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NST) hosted a workshop on standardisation in hypertext, a followup of which will occur during 1990.

The Communications of the ACM special issue on Hypertext contains many references to hypertext papers. A bibliography on hypertext is given in [NIST90], and a uucp newsgroup alt.hypertext exists. I do not, therefore, give a list here.

Browsing techniques

Much of the academic research is into the human interface side of browsing through a complex information space. Problems addressed are those of making navigation easy, and avoiding a feeling of being "lost in hyperspace". Whilst the results of the research are interesting, many users at CERN will be accessing the system using primitive terminals, and so advanced window styles are not so important for us now.

Interconnection or publication?

Most systems available today use a single database. This is accessed by many users by using a distributed file system. There are few products which take Ted Nelson's idea of a wide "docuverse" literally by allowing links between nodes in different databases. In order to do this, some standardisation would be necessary. However, at the standardisation workshop, the emphasis was on standardisation of the format for exchangeable media, nor for networking. This is prompted by the strong push toward publishing of hypermedia information, for example on optical disk. There seems to be a general consensus about the abstract data model which a hypertext system should use.

Many systems have been put together with little or no regard for portability, unfortunately. Some others, although published, are proprietary software which is not for external release. However, there are several interesting projects and more are appearing all the time. Digital's "Compound Document Architecture" (CDA) , for example, is a data model which may be extendible into a hypermedia model, and there are rumours that this is a way Digital would like to go.

Incentives and CALS

The US Department of Defence has given a big incentive to hypermedia research by, in effect, specifying hypermedia documentation for future procurement. This means that all manuals for parts for defence equipment must be provided in hypermedia form. The acronym CALS stands for ªComputer-aided Acquisition and Logistic Support).

There is also much support from the publishing industry, and from librarians whose job it is to organise information.

What will the system look like?

Let us see what components a hypertext system at CERN must have. The only way in which sufficient flexibility can be incorporated is to separate the information storage software from the information display software, with a well defined interface between them. Given the requirement for network access, it is natural to let this clean interface coincide with the physical division between the user and the remote database machine.

This division also is important in order to allow the heterogeneity which is required at CERN (and would be a boon for the world in general).

Fig 2. A client/server model for a distributed hypertext system.

Therefore, an important phase in the design of the system is to define this interface. After that, the development of various forms of display program and of database server can proceed in parallel. This will have been done well if many different information sources, past, present and future, can be mapped onto the definition, and if many different human interface programs can be written over the years to take advantage of new technology and standards.

Accessing Existing Data

The system must achieve a critical usefulness early on. Existing hypertext systems have had to justify themselves solely on new data. If, however, there was an existing base of data of personnel, for example, to which new data could be linked, the value of each new piece of data would be greater.

What is required is a gateway program which will map an existing structure onto the hypertext model, and allow limited (perhaps read-only) access to it. This takes the form of a hypertext server written to provide existing information in a form matching the standard interface. One would not imagine the server actually generating a hypertext database from and existing one: rather, it would generate a hypertext view of an existing database.

Some examples of systems which could be connected in this way are

- uucp News

- This is a Unix electronic conferencing system. A server for uucp news could makes links between notes on the same subject, as well as showing the structure of the conferences.

- VAX/Notes

- This is Digital's electronic conferencing system. It has a fairly wide following in FermiLab, but much less in CERN. The topology of a conference is quite restricting.

- CERNDOC

- This is a document registration and distribution system running on CERN's VM machine. As well as documents, categories and projects, keywords and authors lend themselves to representation as hypertext nodes.

- File systems

- This would allow any file to be linked to from other hypertext documents.

- The Telephone Book

- Even this could even be viewed as hypertext, with links between people and sections, sections and groups, people and floors of buildings, etc.

- The unix manual

- This is a large body of computer-readable text, currently organised in a flat way, but which also contains link information in a standard format ("See also..").

- Databases

- A generic tool could perhaps be made to allow any database which uses a commercial DBMS to be displayed as a hypertext view.

In some cases, writing these servers would mean unscrambling or obtaining details of the existing protocols and/or file formats. It may not be practical to provide the full functionality of the original system through hypertext. In general, it will be more important to allow read access to the general public: it may be that there is a limited number of people who are providing the information, and that they are content to use the existing facilities.

It is sometimes possible to enhance an existing storage system by coding hypertext information in, if one knows that a server will be generating a hypertext representation. In 'news' articles, for example, one could use (in the text) a standard format for a reference to another article. This would be picked out by the hypertext gateway and used to generate a link to that note. This sort of enhancement will allow greater integration between old and new systems.

There will always be a large number of information management systems - we get a lot of added usefulness from being able to cross-link them. However, we will lose out if we try to constrain them, as we will exclude systems and hamper the evolution of hypertext in general.

Conclusion

We should work toward a universal linked information system, in which generality and portability are more important than fancy graphics techniques and complex extra facilities.

The aim would be to allow a place to be found for any information or reference which one felt was important, and a way of finding it afterwards. The result should be sufficiently attractive to use that it the information contained would grow past a critical threshold, so that the usefulness the scheme would in turn encourage its increased use.

The passing of this threshold accelerated by allowing large existing databases to be linked together and with new ones.

A Practical Project

Here I suggest the practical steps to go to in order to find a real solution at CERN. After a preliminary discussion of the requirements listed above, a survey of what is available from industry is obviously required. At this stage, we will be looking for a systems which are future-proof:

- portable, or supported on many platforms,

- Extendible to new data formats.

We may find that with a little adaptation, pars of the system we need can be combined from various sources: for example, a browser from one source with a database from another.

I imagine that two people for 6 to 12 months would be sufficient for this phase of the project.

A second phase would almost certainly involve some programming in order to set up a real system at CERN on many machines. An important part of this, discussed below, is the integration of a hypertext system with existing data, so as to provide a universal system, and to achieve critical usefulness at an early stage.

(... and yes, this would provide an excellent project with which to try our new object oriented programming techniques!) TBL March 1989, May 1990

References

- [NEL67]

- Nelson, T.H. "Getting it out of our system" in Information Retrieval: A Critical Review", G. Schechter, ed. Thomson Books, Washington D.C., 1967, 191-210

- [SMISH88]

- Smish, J.B and Weiss, S.F,"An Overview of Hypertext",in Communications of the ACM, July 1988 Vol 31, No. 7,and other articles in the same special "Hypertext" issue.

- [CAMP88]

- Campbell, B and Goodman, J,"HAM: a general purpose Hypertext Abstract Machine",in Communications of the ACM July 1988 Vol 31, No. 7

- [ASKCYN88]

- Akscyn, R.M, McCracken, D and Yoder E.A,"KMS: A distributed hypermedia system for managing knowledge in originations", in Communications of the ACM , July 1988 Vol 31, No. 7

- [HYP88]

- Hypertext on Hypertext, a hypertext version of the special Comms of the ACM edition, is avialble from the ACM for the Macintosh or PC.

- [RN]

- Under unix, type man rn to find out about the rn command which is used for reading uucp news.

- [NOTES]

- Under VMS, type HELP NOTES to find out about the VAX/NOTES system

- [CERNDOC]

- On CERNVM, type FIND DOCFIND for infrmation about how to access the CERNDOC programs.

- [NIST90]

- J. Moline et. al. (ed.) Proceedings of the Hypertext Standardisation Workshop January 16-18, 1990, National Institute of Standards and Technology, pub. U.S. Dept. of Commerce

- 相关一些历史背景

https://home.cern/news/opinion/computing/internet-prehistory-cern

CERN 的互联网史前史

为了更好的了的让大家了解,我尽量加一些注解或链接在里面

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tim_Berners-Lee 这样一个链接查看中文只需 en换成zh就可以。

退休的 CERN 计算机科学家 Ben Segal 说,将 CERN 连接到互联网是一项混乱但必不可少的任务

我于 1971 年加入 CERN,当时理论上的高能物理学处于混乱状态。CERN 和其他地方的“数据通信”领域同样混乱。各种不同的技术、媒体和协议是惊人的。许多制造商的专有系统、自制系统(包括 CERN 自己的“FOCUS”和“CERNET”)与定义开放或国际标准的初步努力之间存在公开战争。计算机系统或它们之间的通信没有标准。在 CERN,没有 LAN(局域网)、没有 PC(个人电脑,当时的电脑基本都是专业领域解决专业性的问题而开发、制造的) 或 Macintoshes(是自1984年1月起由苹果公司设计、开发和销售的个人电脑系列产品。 Macintosh 128k是第一款成功的面向大众市场的个人电脑)、没有 Unix系统,也没有 C语言编程。

1983 年,CERN 数据处理部 (DD) 首次成立了数据通信 (DC) 组。我在软件 (SW) 组中,该组以前运行过许多 DD 网络项目。新的 DC 小组的任务是统一整个 CERN 的网络,但很快就清楚这不会全面完成。DC 集团决定将该领域的主要部分留给其他人,同时专注于构建 CERN 范围的骨干基础设施。他们还正式强调了 ISO 网络标准,唯一的主要例外是他们对 DECnet 的支持。PC 网络几乎完全被忽略了。IBM 大型机网络(BITNET/EARN 除外)仍属于 SW 组。电子邮件和新闻方面的工作,以及 Unix 和基于工作站的网络的新领域也是如此。

1984 年 8 月,我向 SW 小组组长 Les Robertson 写了一份提案,要求建立一个试点项目,在 CERN 的一些关键非 Unix 机器上安装和评估 TCP/IP 协议,包括中央 IBM-VM 大型机和 VAX VMS系统。这是为了决定 TCP/IP 是否确实可以解决较新的开放系统和已建立的专有系统之间的异构连接问题。该提案获得批准,这项工作导致人们接受 TCP/IP 作为最有前途的解决方案,同时使用“套接字”(由 BSD 4.x Unix 系统开创)作为推荐的 API。

1985 年初,作为 SW 集团和 DC 集团正式协议的一部分,我被任命为 CERN 的“TCP/IP 协调员”。DC 的政策特别限制了在 CERN 站点内使用的互联网协议。不能使用 TCP/IP 建立外部连接:在这里,ISO/IBM/DE Cnet 垄断仍然占据着至高无上的地位,直到 1989 年初。

1985 年到 1988 年间,尽管参与的人数很少,但在 CERN 内协调引入 TCP/IP 取得了显着进展。所涉及的技术基本上很简单,并且越来越容易购买和安装。1985 年 11 月,LEP 的管理层决定将 TCP/IP 用于 27 公里长的大型正负电子对撞机(LEP) 的控制系统,这是向前迈出的重要一步。这一决定,再加上他们后来决定使用基于 Unix 的系统,结果证明对于 LEP 的成功至关重要。

1988年,DC组(后改名为CN分部CS组)终于同意承担TCP/IP的支持。曾经是 SW 集团的小规模运作变成了人员配备和组织得当的活动。在 1989 年 1 月“大爆炸”之后,欧洲核子研究中心开通了第一个外部互联网连接,将所有 IP 地址更改为官方地址。

一个关键的结果是,到 1989 年,欧洲核子研究中心的互联网设施已准备好成为Tim Berners-Lee创建万维网的媒介。CERN 围绕“分布式计算”发展了一种完整的文化,Tim 在远程过程调用 (RPC) 领域做出了贡献,掌握了实现 Web 所需的几个工具,例如软件可移植性技术以及网络和套接字编程.

我个人认为,如果 CERN 更早地连接到互联网,那么网络可能会更早出现。Tim Berners-Lee 的 第一个 Web 提案 是在 CERN 的第一个外部连接开通后立即编写的,并且 Tim Berners-Lee 自 1980 年以来一直在研究超文本创意,这受到 Ted Nelson 在 Xanadu 等方面的工作的影响。但这仍停留在猜测领域。可以肯定的是,互联网为我们欧洲核子研究中心的一些人提供了一个独特的机会,让他们参与一系列为无数人改变世界的活动,并将继续这样做,希望会变得更好。

这是 Ben Segal 的“ CERN 互联网协议简史”的编辑和删节版

网络简史(着重万维网)

https://home.web.cern.ch/science/computing/birth-web/short-history-web

网络诞生的地方

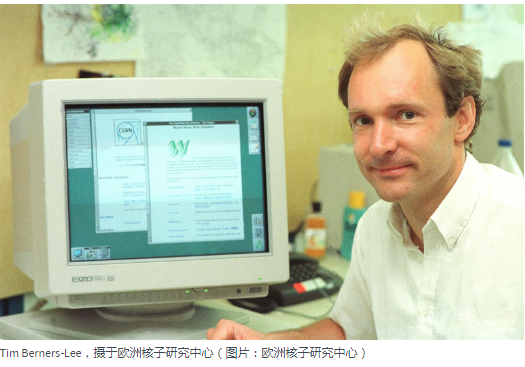

英国科学家蒂姆·伯纳斯-李 (Tim Berners-Lee) 于 1989 年在 CERN 工作时发明了万维网 (WWW)。Web 最初的构想和开发是为了满足世界各地大学和研究所的科学家之间对自动信息共享的需求。

CERN 不是一个孤立的实验室,而是一个广泛的社区的焦点,该社区包括来自 100 多个国家的 17 000 多名科学家。虽然他们通常会在 CERN 网站上花费一些时间,但科学家们通常在本国的大学和国家实验室工作。因此,可靠的通信工具至关重要。

万维网的基本思想是将不断发展的计算机、数据网络和超文本技术合并成一个功能强大且易于使用的全球信息系统。

网络是如何开始的

Tim Berners-Lee 的万维网提案的第一页,写于 1989 年 3 月(图片:CERN)

Tim Berners-Lee 在 1989 年 3 月编写了第一个万维网提案,在 1990 年 5 月编写了第二个提案。1990 年 11 月,与比利时系统工程师 Robert Cailliau 一起,这被正式确定为管理提案。它概述了主要概念并定义了 Web 背后的重要术语。该文件描述了一个名为“WorldWideWeb”的“超文本项目”,其中“浏览器”可以查看“超文本文档”的“网络”。

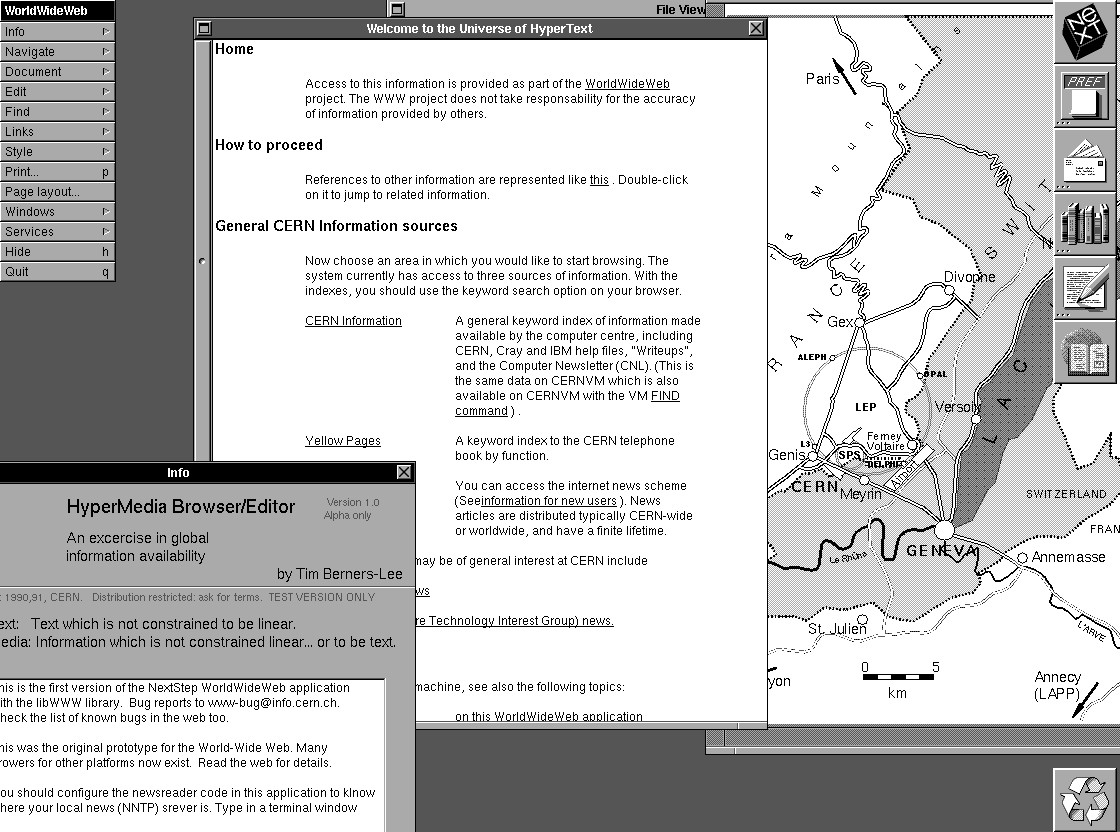

到 1990 年底,Tim Berners-Lee 在 CERN 启动并运行了第一台 Web 服务器和浏览器,展示了他的想法。他在 NeXT 计算机上为他的 Web 服务器开发了代码。为防止意外关机,电脑上用红墨水手写了一个标签:“本机是服务器,请勿关机!!

1990 年 Tim Berners-Lee 用于开发和运行第一台 WWW 服务器、多媒体浏览器和 Web 编辑器的 NeXT 机器的复制品(图片:Maximilien Brice/Anna Pantelia/CERN)

此页面包含指向有关 WWW 项目本身的信息的链接,包括对超文本的描述、创建 Web 服务器的技术细节以及与其他可用 Web 服务器的链接

info.cern.ch是世界上第一个网站和 Web 服务器的地址,运行在 CERN 的 NeXT 计算机上。第一个网页地址是 http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html

显示由 Tim Berners-Lee 创建的 NeXT 万维网浏览器的屏幕截图(图片:CERN)

WWW 设计允许轻松访问现有信息和链接到对 CERN 科学家有用的信息的早期网页(例如 CERN 电话簿和使用 CERN 中央计算机的指南)。

搜索工具依赖于关键字——早年没有搜索引擎。Berners-Lee 最初在 NeXT 计算机上运行的 Web 浏览器显示了他的远见,

并具有当前 Web 浏览器的许多功能。此外,它还包括直接从浏览器内部修改页面的能力——第一个 Web 编辑功能。

此屏幕截图显示了1993 年在 NeXT 计算机上运行的浏览器。

网络扩展

只有少数用户可以访问运行第一个浏览器的 NeXT 计算机平台,但很快就开始开发一种更简单的“行模式”浏览器,它可以在任何系统上运行。它是 Nicola Pellow(是CERN与 Berners-Lee 合作的WWW项目十九名成员之一) 在 CERN 的学生实习期间写的。1991 年,Berners-Lee 发布了他的 WWW 软件。它包括“线路模式”浏览器、Web 服务器软件和开发人员库。1991 年 3 月,该软件可供使用 CERN 计算机的同事使用。几个月后,即 1991 年 8 月,他在 Internet Newsgroup 上宣布了 WWW 软件,并且把该项目传遍了世界各地。

走向全球

由于 Paul Kunz(GNUstep,GNU计划的项目之一,GNUstep最早是由保罗·昆茨(Paul Kunz)与其他在史丹福线性加速器中心的同事所撰写) 和 Louise Addis 的努力,美国的第一台 Web 服务器于 1991 年 12 月上线,再次在粒子物理实验室:斯坦福直线加速器中心(SLAC) 在加利福尼亚。在这个阶段,基本上只有两种浏览器。一个是最初的开发版本,它很复杂,但只能在 NeXT 机器上使用。另一种是“线路模式”浏览器,它易于在任何平台上安装和运行,但功能和用户友好性有限。很明显,CERN 的小团队无法完成进一步开发该系统所需的所有工作,因此 Berners-Lee 通过互联网发起了呼吁其他开发人员加入的请求。有几个人编写了浏览器,主要用于 X-Window系统。其中值得注意的是来自 SLAC 的 Tony Johnson 的 MIDAS、技术出版商 O'Reilly Books 的 Pei Wei 的 Viola,以及来自赫尔辛基理工大学的芬兰学生的 Erwise。

1993 年初,美国国家超级计算应用中心伊利诺伊大学 (NCSA) 发布了其 Mosaic 浏览器的第一个版本。该软件在研究界流行的 X Window System 环境中运行,并提供友好的基于窗口的交互。不久之后,NCSA 也发布了适用于 PC 和 Macintosh 环境的版本。这些流行计算机上可靠的用户友好型浏览器的存在对万维网的传播产生了直接影响。同年年底,欧盟委员会批准了其第一个网络项目 (WISE),其中 CERN 是合作伙伴之一。

1993 年 4 月 30 日,CERN(欧洲核子研究中心)免费提供 WorldWideWeb 的源代码,使其成为免费软件。到 1993 年底,已知的网络服务器超过 500 台,万维网占互联网流量的 1%,这在当时似乎很多(其余的是远程访问,电子邮件和文件传输)。1994 年是“网络年”。由罗伯特·卡约发起,首届国际万维网会议于 5 月在 CERN 举行。有380 名用户和开发者参加,被誉为“网络的伍德斯托克”。随着 1994 年的发展,有关 Web 的故事登上了媒体。由 NCSA 和新成立的国际 WWW 会议委员会(IW3C2)于 10 月在美国举行了第二次会议,有 1300 人参加。到 1994 年底,Web 拥有 10000 台服务器(其中 2000 台是商业服务器)和 1000 万用户。流量相当于每秒运送莎士比亚的全部作品。该技术不断扩展以满足新的需求。电子商务的安全性和工具是即将添加的最重要的功能。

开放标准

一个要点是,网络应该保持一个开放的标准供所有人使用,并且没有人应该将其锁定在专有系统中。本着这种精神,CERN 根据 ESPRIT 计划向欧盟委员会提交了一份提案:“WebCore”。该项目的目标是与美国麻省理工学院 (MIT) 合作组建一个国际财团。1994年,伯纳斯-李离开欧洲核子研究中心加入麻省理工学院,创立了国际万维网联盟(W3C)。同时,随着大型强子对撞机项目的批准,CERN 决定进一步开发网络是一项超出实验室主要任务的活动。W3C 需要一个新的欧洲合作伙伴。欧盟委员会求助于法国国家计算机科学与控制研究所 (INRIA),以接管 CERN 的角色。1995 年 4 月,INRIA 成为第一个欧洲 W3C 主办方, 1996 年日本庆应大学(湘南藤泽校区)在亚洲成为第一个。2003 年,ERCIM(欧洲信息学和数学研究联盟)接任欧洲 W3C 主办方的角色。 INRIA。2013年,W3C宣布 北航 为第四届主办方。2018年9月,来自世界各地的会员组织超过400家。

- 一些参考资料

-

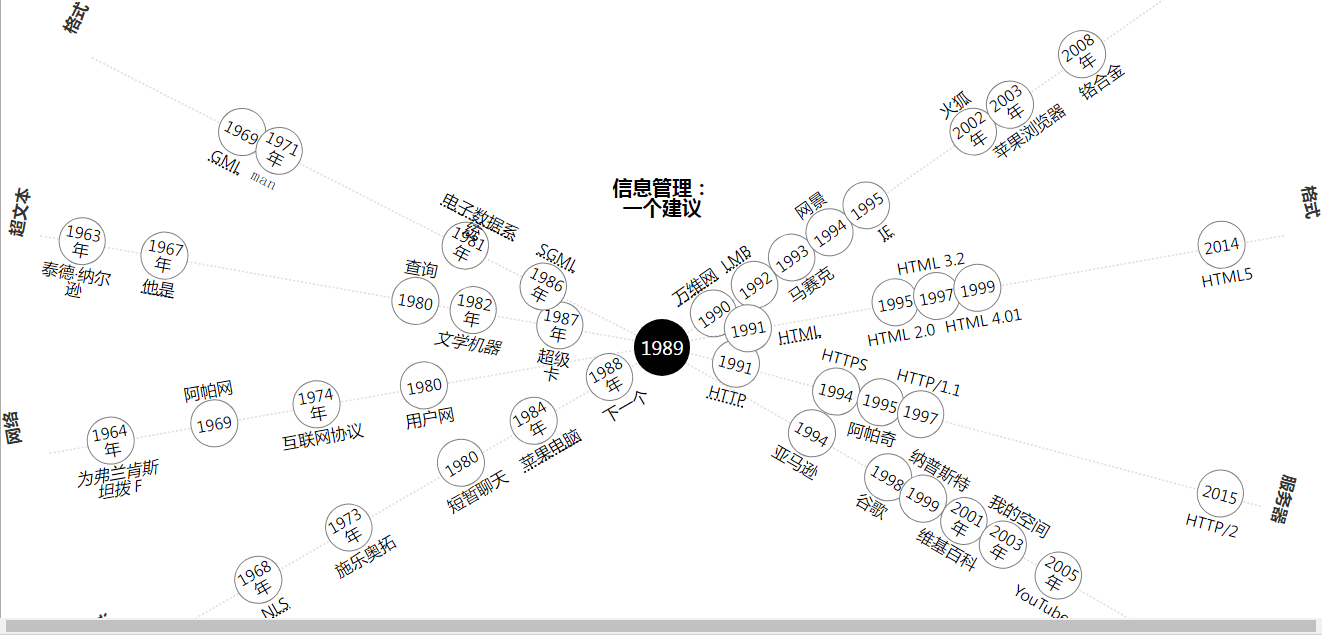

历史时间线 :包括超文本、浏览器、格式、网络、http服务器等。时间交叉和交汇情况。(第一次见过这样的交汇图)