Python自然语言处理学习笔记(18):3.2 字符串:最底层的文本处理

转载请注明出处“一块努力的牛皮糖”:http://www.cnblogs.com/yuxc/

3.2 Strings: Text Processing at the Lowest Level 字符串:最底层的文本处理

PS:个人认为这部分很重要,字符串处理是NLP里最基本的部分,各位童鞋好好看,老鸟略过...

It’s time to study a fundamental data type that we’ve been studiously(故意地) avoiding so far. In earlier chapters we focused on a text as a list of words. We didn’t look too closely at words and how they are handled in the programming language. By using NLTK’s corpus interface we were able to ignore the files that these texts had come from. The contents of a word, and of a file, are represented by programming languages as a fundamental data type known as a string. In this section, we explore strings in detail, and show the connection between strings, words, texts, and files.

Basic Operations with Strings 字符串的基本操作

Strings are specified using single quotes ①or double quotes②, as shown in the following code example. If a string contains a single quote, we must backslash-escape the quote③ so Python knows a literal quote character is intended, or else put the string in double quotes②. Otherwise, the quote inside the string④will be interpreted as a close quote, and the Python interpreter will report a syntax error:

>>> monty

'Monty Python'

>>> circus = "Monty Python's Flying Circus" ②

>>> circus

"Monty Python's Flying Circus"

>>> circus = 'Monty Python\'s Flying Circus' ③

>>> circus

"Monty Python's Flying Circus"

>>> circus = 'Monty Python's Flying Circus' ④

File "<stdin>", line 1

circus = 'Monty Python's Flying Circus'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Sometimes strings go over several lines. Python provides us with various ways of entering them. In the next example, a sequence of two strings is joined into a single string. We need to use backslash ① or parentheses ② so that the interpreter knows that the statement is not complete after the first line.

... "Thou are more lovely and more temperate:" ①

>>> print couplet

Shall I compare thee to a Summer's day?Thou are more lovely and more temperate:

>>> couplet = ("Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,"

... "And Summer's lease hath all too short a date:") ②

>>> print couplet

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,And Summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Unfortunately these methods do not give us a newline between the two lines of the sonnet(十四行诗). Instead, we can use a triple-quoted string as follows:

... Thou are more lovely and more temperate:"""

>>> print couplet

Shall I compare thee to a Summer's day?

Thou are more lovely and more temperate:

>>> couplet = '''Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

... And Summer's lease hath all too short a date:'''

>>> print couplet

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And Summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Now that we can define strings, we can try some simple operations on them. First let’s look at the + operation, known as concatenation ① . It produces a new string that is a copy of the two original strings pasted together end-to-end(首尾相连). Notice that concatenation doesn’t do anything clever like insert a space between the words. We can even multiply strings②:

'veryveryvery'

>>> 'very' * 3 ②

'veryveryvery'

Your Turn: Try running the following code, then try to use your understanding of the string + and * operations to figure out how it works. Be careful to distinguish between the string ' ', which is a single whitespace character, and '', which is the empty string.

>>> b = [' ' * 2 * (7 - i) + 'very' * i for i in a]

>>> for line in b:

... print b

We’ve seen that the addition and multiplication operations apply to strings, not just numbers. However, note that we cannot use subtraction or division with strings:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'

>>> 'very' / 2

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'int'

These error messages are another example of Python telling us that we have got our data types in a muddle(困惑). In the first case, we are told that the operation of subtraction (i.e., -) cannot apply to objects of type str (strings), while in the second, we are told that division cannot take str and int as its two operands.

Printing Strings 打印字符串

So far, when we have wanted to look at the contents of a variable or see the result of a calculation, we have just typed the variable name into the interpreter. We can also see the contents of a variable using the print statement:

Monty Python

Notice that there are no quotation marks this time. When we inspect a variable by typing its name in the interpreter, the interpreter prints the Python representation of its value. Since it’s a string, the result is quoted. However, when we tell the interpreter to print the contents of the variable, we don’t see quotation characters, since there are none inside the string.

The print statement allows us to display more than one item on a line in various ways,

as shown here:

>>> print monty + grail

Monty PythonHoly Grail

>>> print monty, grail

Monty Python Holy Grail

>>> print monty, "and the", grail #会在词之间自动添加空格

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Accessing Individual Characters 访问单独的字符

As we saw in Section 1.2 for lists, strings are indexed, starting from zero. When we index a string, we get one of its characters (or letters). A single character is nothing special—it’s just a string of length 1.

'M'

>>> monty[3]

't'

>>> monty[5]

' '

As with lists, if we try to access an index that is outside of the string, we get an error:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

IndexError: string index out of range

Again as with lists, we can use negative indexes for strings, where -1 is the index of the last character①. Positive and negative indexes give us two ways to refer to any position in a string. In this case, when the string had a length of 12, indexes 5 and -7 both refer to the same character (a space). (Notice that 5 = len(monty) - 7.)

'n'

>>> monty[5]

' '

>>> monty[-7]

' '

We can write for loops to iterate over the characters in strings. This print statement ends with a trailing comma, which is how we tell Python not to print a newline at the end.

>>> for char in sent:

... print char,

...

c o l o r l e s s g r e e n i d e a s s l e e p f u r i o u s l y

We can count individual characters as well. We should ignore the case distinction by normalizing everything to lowercase, and filter out non-alphabetic characters:

>>> raw = gutenberg.raw('melville-moby_dick.txt')

>>> fdist = nltk.FreqDist(ch.lower() for ch in raw if ch.isalpha())

>>> fdist.keys()

['e', 't', 'a', 'o', 'n', 'i', 's', 'h', 'r', 'l', 'd', 'u', 'm', 'c', 'w',

'f', 'g', 'p', 'b', 'y', 'v', 'k', 'q', 'j', 'x', 'z']

This gives us the letters of the alphabet, with the most frequently occurring letters listed first (this is quite complicated and we’ll explain it more carefully later). You might like to visualize the distribution using fdist.plot(). The relative character frequencies of a text can be used in automatically identifying the language of the text.

Accessing Substrings 访问子字符串

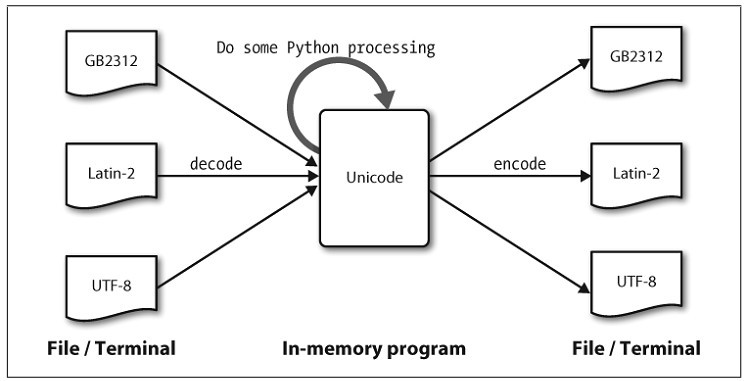

A substring is any continuous section of a string that we want to pull out(取出) for further processing. We can easily access substrings using the same slice notation we used for lists (see Figure 3-2). For example, the following code accesses the substring starting at index 6, up to (but not including) index 10:

'Pyth'

Figure 3-2. String slicing字符串切片: The string Monty Python is shown along with its positive and negative indexes; two substrings are selected using “slice” notation. The slice [m,n] contains the characters from position m through n-1.

Here we see the characters are 'P', 'y', 't', and 'h', which correspond to monty[6] ...monty[9] but not monty[10]. This is because a slice starts at the first index but finishes one before the end index.

We can also slice with negative indexes—the same basic rule of starting from the start index and stopping one before the end index applies; here we stop before the space character.

'Monty'

As with list slices, if we omit the first value, the substring begins at the start of the string.

If we omit the second value, the substring continues to the end of the string:

'Monty'

>>> monty[6:]

'Python'

We test if a string contains a particular substring using the in operator, as follows:

>>> if 'thing' in phrase:

... print 'found "thing"'

found "thing"

We can also find the position of a substring within a string, using find():

6

Your Turn: Make up a sentence and assign it to a variable, e.g., sent = 'my sentence...'. Now write slice expressions to pull out individual words. (This is obviously not a convenient way to process the words of a text!)

More Operations on Strings 更多的字符串操作

Python has comprehensive(全面的)support for processing strings. A summary, including some operations we haven’t seen yet, is shown in Table 3-2. For more information on strings, type help(str) at the Python prompt.

Table 3-2. Useful string methods: Operations on strings in addition to the string tests shown in Table 1-4; all methods produce a new string or list

Method Functionality

s.find(t) Index of first instance of string t inside s (-1 if not found)

s.rfind(t) Index of last instance of string t inside s (-1 if not found)

s.index(t) Like s.find(t), except it raises ValueError if not found

s.rindex(t) Like s.rfind(t), except it raises ValueError if not found

s.join(text) Combine the words of the text into a string using s as the glue

s.split(t) Split s into a list wherever a t is found (whitespace by default)

s.splitlines() Split s into a list of strings, one per line

s.lower() A lowercased version of the string s

s.upper() An uppercased version of the string s

s.titlecase() A titlecased version of the string s

s.strip() A copy of s without leading or trailing whitespace

s.replace(t, u) Replace instances of t with u inside s

The Difference Between Lists and Strings 列表和字符串之间的不同

Strings and lists are both kinds of sequence. We can pull them apart by indexing and slicing them, and we can join them together by concatenating them. However, we can not join strings and lists:

>>> beatles = ['John', 'Paul', 'George', 'Ringo']

>>> query[2]

'o'

>>> beatles[2]

'George'

>>> query[:2]

'Wh'

>>> beatles[:2]

['John', 'Paul']

>>> query + " I don't"

"Who knows? I don't"

>>> beatles + 'Brian'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: can only concatenate list (not "str") to list

>>> beatles + ['Brian']

['John', 'Paul', 'George', 'Ringo', 'Brian']

When we open a file for reading into a Python program, we get a string corresponding to the contents of the whole file. If we use a for loop to process the elements of this string, all we can pick out (挑选出)are the individual characters—we don’t get to choose the granularity. By contrast, the elements of a list can be as big or small as we like: for example, they could be paragraphs, sentences, phrases, words, characters. So lists have the advantage that we can be flexible about the elements they contain, and correspondingly flexible about any downstream(后阶段的) processing. Consequently, one of the first things we are likely to do in a piece of NLP code is tokenize a string into a list of strings (Section 3.7). Conversely, when we want to write our results to a file, or to a terminal, we will usually format them as a string (Section 3.9). Lists and strings do not have exactly the same functionality. Lists have the added power that you can change their elements:

>>> del beatles[-1]

>>> beatles

['John Lennon', 'Paul', 'George']

On the other hand, if we try to do that with a string—changing the 0th character in query to 'F'—we get:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

TypeError: object does not support item assignment

This is because strings are immutable(不可变的): you can’t change a string once you have created it. However, lists are mutable, and their contents can be modified at any time. As a result, lists support operations that modify the original value rather than producing a new value.

Your Turn: Consolidate your knowledge of strings by trying some of the exercises on strings at the end of this chapter.