Python自然语言处理学习笔记(5):1.3 语言计算:简单的统计

新手上路,翻译不恰之处,恳请指出,不胜感谢![]()

Updated log:

1.3 Computing with Language: Simple Statistics 语言计算:简单的统计

Let' s return to our exploration of the ways we can bring our computational resources to bear on large quantities of text. We began this discussion in Section 1.1, and saw how to search for words in context, how to compile the vocabulary of a text, how to generate random text in the same style, and so on.

In this section, we pick up the question of what makes a text distinct, and use automatic methods to find characteristic words and expressions of a text. As in Section 1.1, you can try new features of the Python language by copying them into the interpreter, and you' ll learn about these features systematically in the following section.

Before continuing further, you might like to check your understanding of the last section by predicting the output of the following code. You can use the interpreter to check whether you got it right. If you’re not sure how to do this task, it would be a good idea to review the previous section before continuing further.

... 'more', 'is', 'said', 'than', 'done']

>>> tokens = set(saying)

>>> tokens = sorted(tokens)

>>> tokens[-2:]

what output do you expect here?

>>>

Frequency Distributions 频率分布

How can we automatically identify the words of a text that are most informative(有益的) about the topic and genre(风格) of the text? Imagine how you might go about finding the 50 most frequent words of a book. One method would be to keep a tally(计数器) for each vocabulary item, like that shown in Figure 1-3. The tally would need thousands of rows, and it would be an exceedingly laborious process—so laborious that we would rather assign the task to a machine.

Figure 1-3. Counting words appearing in a text (a frequency distribution).

The table in Figure 1-3 is known as a frequency distribution , and it tells us the frequency of each vocabulary item in the text. (In general, it could count any kind of observable event.) It is a “distribution”since it tells us how the total number of word tokens in the text are distributed across the vocabulary items. Since we often need frequency distributions in language processing, NLTK provides built-in support for them. Let’ s use a FreqDist to find the 50 most frequent words of Moby Dick. Try to work out what is going on here, then read the explanation that follows.

>>> fdist1 ②

<FreqDist with 260819 outcomes>

>>> vocabulary1 = fdist1.keys() ③

>>> vocabulary1[:50] ④

[',', 'the', '.', 'of', 'and', 'a', 'to', ';', 'in', 'that', "'", '-','his', 'it', 'I', 's', 'is', 'he', 'with', 'was', 'as', '"', 'all', 'for','this', '!', 'at', 'by', 'but', 'not', '--', 'him', 'from', 'be', 'on','so', 'whale', 'one', 'you', 'had', 'have', 'there', 'But', 'or', 'were','now', 'which', '?', 'me', 'like']

>>> fdist1['whale']

906

>>>

When we first invoke FreqDist, we pass the name of the text as an argument①. We can inspect the total number of words (“outcomes”) that have been counted up②—260,819 in the case of Moby Dick. The expression keys() gives us a list of all the distinct types in the text③, and we can look at the first 50 of these by slicing the list④.

Your Turn: Try the preceding frequency distribution example for yourself, for text2. Be careful to use the correct parentheses and uppercase letters. If you get an error message NameError: name 'FreqDist' is not defined, you need to start your work with from nltk.book import *.

Your Turn: Try the preceding frequency distribution example for yourself, for text2. Be careful to use the correct parentheses and uppercase letters. If you get an error message NameError: name 'FreqDist' is not defined, you need to start your work with from nltk.book import *.

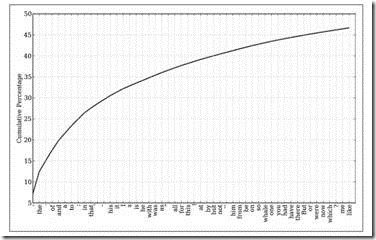

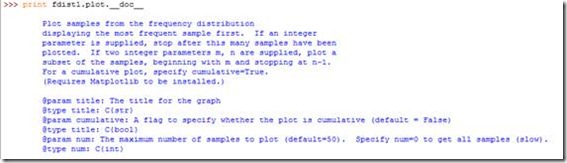

Do any words produced in the last example help us grasp the topic or genre of this text? Only one word, whale, is slightly informative! It occurs over 900 times. The rest of the words tell us nothing about the text; they’re just English “plumbing.” What proportion(比例) of the text is taken up with such words? We can generate a cumulative(累计的) frequency plot for these words, using fdist1.plot(50, cumulative=True), to produce the graph in Figure 1-4. These 50 words account for nearly half the book!

Figure 1-4. Cumulative frequency plot for the 50 most frequently used words in Moby Dick, which account for nearly half of the tokens

原图纵坐标是百分比,我这里出来的是数量,查了下doc,发现貌似没有百分比的参数选择呀

If the frequent words don’t help us, how about the words that occur once only, the so-called hapaxes? View them by typing fdist1.hapaxes(). This list contains lexicographer, cetological(鲸类学的), contraband(走私), expostulations(劝告), and about 9,000 others. It seems that there are too many rare words, and without seeing the context we probably can’t guess what half of the hapaxes mean in any case! Since neither frequent nor infrequent words help, we need to try something else.因为高频和低频的单词都没有任何帮助,我们需要尝试其他的办法。

Fine-Grained Selection of Words 单词的细粒度选择(精选)

Next, let’s look at the long words of a text; perhaps these will be more characteristic and informative. For this we adapt some notation from set theory(集合论). We would like to find the words from the vocabulary of the text that are more than 15 characters long. Let’s call this property P, so that P(w) is true if and only if w is more than 15 characters long. Now we can express the words of interest using mathematical set notation as shown in (1a). This means “the set of all w such that w is an element of V (the vocabulary) and w has property P.”

(1) a. {w | w ∈ V & P(w)} 对于集合中所有的w,w∈V且P(w)

b. [w for w in V if p(w)] Python 表达式

The corresponding Python expression is given in (1b). (Note that it produces a list, not a set, which means that duplicates are possible.产生的是列表,不是集合,可能会有相同的元素) Observe how similar the two notations are. Let’s go one more step and write executable Python code:

>>> long_words = [w for w in V if len(w) > 15]

>>> sorted(long_words)

['CIRCUMNAVIGATION', 'Physiognomically', 'apprehensiveness', 'cannibalistically',

'characteristically', 'circumnavigating', 'circumnavigation', 'circumnavigations',

'comprehensiveness', 'hermaphroditical', 'indiscriminately', 'indispensableness',

'irresistibleness', 'physiognomically', 'preternaturalness', 'responsibilities',

'simultaneousness', 'subterraneousness', 'supernaturalness', 'superstitiousness',

'uncomfortableness', 'uncompromisedness', 'undiscriminating', 'uninterpenetratingly']

>>>

For each word w in the vocabulary V, we check whether len(w) is greater than 15; all other words will be ignored. We will discuss this syntax more carefully later.

Your Turn: Try out the previous statements in the Python interpreter, and experiment with changing the text and changing the length condition. Does it make an difference to your results if you change the variable names, e.g., using [word for word in vocab if ...]?

Let’s return to our task of finding words that characterize a text. Notice that the long words in text4 reflect its national focus—constitutionally(本质地), transcontinental(横贯大陆的)—whereas those in text5 reflect its informal content(非正式的内容): boooooooooooglyyyyyy and yuuuuuuuuuuuummmmmmmmmmmm. Have we succeeded in automatically extracting words that typify a text? Well, these very long words are often hapaxes (i.e., unique独一无二) and perhaps it would be better to find frequently occurring long words. This seems promising since it eliminates frequent short words (e.g., the) and infrequent long words (e.g., antiphilosophists). Here are all words from the chat corpus that are longer than seven characters, that occur more than seven times:

>>> sorted([w for w in set(text5) if len(w) > 7 and fdist5[w] > 7])

['#14-19teens', '#talkcity_adults', '((((((((((', '........', 'Question',

'actually', 'anything', 'computer', 'cute.-ass', 'everyone', 'football',

'innocent', 'listening', 'remember', 'seriously', 'something', 'together',

'tomorrow', 'watching']

>>>

Notice how we have used two conditions: len(w) > 7 ensures that the words are longer than seven letters, and fdist5[w] > 7 ensures that these words occur more than seven times. At last we have managed to automatically identify the frequently occurring content-bearing(与内容有关系的) words of the text. It is a modest(谦虚的) but important milestone: a tiny piece of code, processing tens of thousands of words, produces some informative output.

Collocations and Bigrams 词语搭配和双连词(自然语言处理及计算语言学相关术语)

A collocation is a sequence of words that occur together unusually often. Thus red wine is a collocation, whereas the wine is not. A characteristic of collocations is that they are resistant to (对…有抵抗力的)substitution(置换) with words that have similar senses; for example, maroon wine(粟色酒) sounds very odd.

To get a handle on(处理) collocations, we start off(开始) by extracting from a text a list of word pairs(词对), also known as bigrams. This is easily accomplished with the function bigrams():

[('more', 'is'), ('is', 'said'), ('said', 'than'), ('than', 'done')]

>>>

Here we see that the pair of words than-done is a bigram, and we write it in Python as ('than', 'done'). Now, collocations are essentially just frequent bigrams, except that we want to pay more attention to the cases that involve rare words. In particular, we want to find bigrams that occur more often than we would expect based on the frequency of individual words. The collocations() function does this for us (we will see how it works later):

Building collocations list

United States; fellow citizens; years ago; Federal Government; General

Government; American people; Vice President; Almighty God; Fellow

citizens; Chief Magistrate; Chief Justice; God bless; Indian tribes;

public debt; foreign nations; political parties; State governments;

National Government; United Nations; public money

>>> text8.collocations()

Building collocations list

medium build; social drinker; quiet nights; long term; age open;

financially secure; fun times; similar interests; Age open; poss

rship; single mum; permanent relationship; slim build; seeks lady;

Late 30s; Photo pls; Vibrant personality; European background; ASIAN

LADY; country drives

>>>

The collocations that emerge(出现) are very specific to the genre of the texts(对于文本的风格是很明确的). In order to find red wine as a collocation, we would need to process a much larger body of text.

Counting Other Things 计数其他东东

Counting words is useful, but we can count other things too. For example, we can look at the distribution of word lengths in a text, by creating a FreqDist out of a long list of numbers, where each number is the length of the corresponding word in the text:

[1, 4, 4, 2, 6, 8, 4, 1, 9, 1, 1, 8, 2, 1, 4, 11, 5, 2, 1, 7, 6, 1, 3, 4, 5, 2, ...]

>>> fdist = FreqDist([len(w) for w in text1]) ②

>>> fdist ③

<FreqDist with 260819 outcomes>

>>> fdist.keys()

[3, 1, 4, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20]

>>>

We start by deriving(获得) a list of the lengths of words in text1①, and the FreqDist then counts the number of times each of these occurs②. The result③ is a distribution containing a quarter of (四分之一)a million items, each of which is a number corresponding to a word token in the text(就是把单词按长度来排,统计它们的频率). But there are only 20 distinct items being counted, the numbers 1 through 20, because there are only 20 different word lengths. I.e., there are words consisting of just 1 character, 2 characters, ..., 20 characters, but none with 21 or more characters. One might wonder how frequent the different lengths of words are (e.g., how many words of length 4 appear in the text, are there more words of length 5 than length 4, etc.). We can do this as follows:

[(3, 50223), (1, 47933), (4, 42345), (2, 38513), (5, 26597), (6, 17111), (7, 14399),

(8, 9966), (9, 6428), (10, 3528), (11, 1873), (12, 1053), (13, 567), (14, 177),

(15, 70), (16, 22), (17, 12), (18, 1), (20, 1)]

>>> fdist.max()

3

>>> fdist[3]

50223

>>> fdist.freq(3)

0.19255882431878046

>>>

From this we see that the most frequent word length is 3, and that words of length 3 account for roughly 50,000 (or 20%) of the words making up the book. Although we will not pursue it here, further analysis of word length might help us understand differences between authors, genres, or languages. Table 1-2 summarizes the functions defined in frequency distributions.

Table 1-2. Functions defined for NLTK’s frequency distributions

|

Example |

Description |

|

fdist = FreqDist(samples) |

Create a frequency distribution containing the given samples |

|

fdist.inc(sample) |

Increment the count for this sample |

|

fdist['monstrous'] |

Count of the number of times a given sample occurred |

|

fdist.freq('monstrous') |

fdist.freq('monstrous') |

|

fdist.N() |

Total number of samples |

|

fdist.keys() |

The samples sorted in order of decreasing frequency |

|

for sample in fdist: |

Iterate over the samples, in order of decreasing frequency |

|

fdist.max() |

Sample with the greatest count |

|

fdist.tabulate() |

Tabulate the frequency distribution |

|

fdist.plot() |

Graphical plot of the frequency distribution |

|

fdist.plot(cumulative=True) |

Cumulative plot of the frequency distribution |

|

fdist1 < fdist2 |

Test if samples in fdist1 occur less frequently than in fdist2 |

Our discussion of frequency distributions has introduced some important Python concepts, and we will look at them systematically in Section 1.4.