Python之路【第九篇】:面向对象进阶

阅读目录

一. isinstance(obj,cls)和issubclass(sub,super)

二. 反射

三. __setattr__,__delattr__,__getattr__

四. 二次加工标准类型(包装)

五. __getattribute__

六. 描述符(__get__,__set__,__delete__)

六. 再看property

七. __setitem__,__getitem,__delitem__

八. __str__,__repr__,__format__

九. __next__和__iter__实现迭代器协议

十. __doc__

十一. __module__和__class__

十二. __del__

十三. __enter__和__exit__

十四. __call__

十五. eval(),exec()

十六. 元类(metaclass)

一. isinstance(obj,cls)和issubclass(sub,super)

isinstance(obj,cls)检查是否obj是否是类 cls 的对象

class Student(object): pass obj = Student() res=isinstance(obj, Student) print(res) ''' True '''

issubclass(sub, super)检查sub类是否是 super 类的派生类

class People(object): pass class Student(People): pass res=issubclass(Student, People) print(res) ''' True '''

二. 反射

2.1 什么是反射

反射的概念是由Smith在1982年首次提出的,主要是指程序可以访问、检测和修改它本身状态或行为的一种能力(自省)。这一概念的提出很快引发了计算机科学领域关于应用反射性的研究。它首先被程序语言的设计领域所采用,并在Lisp和面向对象方面取得了成绩。

2.2 python面向对象中的反射

通过字符串的形式操作对象相关的属性。python中的一切事物都是对象(都可以使用反射)

四个可以实现自省的函数

下列方法适用于类和对象(一切皆对象,类本身也是一个对象)

#判断一个对象里面是否有name属性或者name方法,返回BOOL值,有name特性返回True, 否则返回False。 hasattr(object, name) >>> class test(): ... name="xiaohua" ... def run(self): ... return "HelloWord" ... >>> t=test() >>> hasattr(t, "name") #判断对象有name属性 True >>> hasattr(t, "run") #判断对象有run方法 True

#获取对象object的属性或者方法,如果存在打印出来,如果不存在,打印出默认值,默认值可选。 #需要注意的是,如果是返回的对象的方法,返回的是方法的内存地址,如果需要运行这个方法,可以在后面添加一对括号。 >>> class test(): ... name="shuke" ... def run(self): ... return "HelloWord" ... >>> t=test() >>> getattr(t, "name") #获取name属性,存在就打印出来。 'shuke' >>> getattr(t, "run") #获取run方法,存在就打印出方法的内存地址。 <bound method test.run of <__main__.test instance at 0x0269C878>> >>> getattr(t, "run")() #获取run方法,后面加括号可以将这个方法运行。 'HelloWord' >>> getattr(t, "age") #获取一个不存在的属性。 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> AttributeError: test instance has no attribute 'age' >>> getattr(t, "age","18") #若属性不存在,返回一个默认值。 '18' >>>

#给对象的属性赋值,若属性不存在,先创建再赋值。 >>> class test(): ... name="shuke" ... def run(self): ... return "HelloWord" ... >>> t=test() >>> hasattr(t, "age") #判断属性是否存在 False >>> setattr(t, "age", "18") #为属相赋值,并没有返回值 >>> hasattr(t, "age") #属性存在了 True >>>

#而delattr()表示你可以通过该方法,删除指定的对象属性。 #delattr方法接受2个参数:delattr(对象,属性) >>> class test(): ... name="shuke" ... def run(self): ... return "HelloWord" ... >>> getattr(test,'name') # 删除前 'shuke' >>> delattr(test,'name') # 删除 >>> getattr(test,'name') # 删除后,报错 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> AttributeError: type object 'test' has no attribute 'name'

class Foo(object): staticField = "old boy" def __init__(self): self.name = 'wupeiqi' def func(self): return 'func' @staticmethod def bar(): return 'bar' print getattr(Foo, 'staticField') print getattr(Foo, 'func') print getattr(Foo, 'bar') 类也是对象

#!/usr/bin/env python #-*- coding:utf-8 -*- import sys def s1(): print('s1') def s2(): print('s2') this_module = sys.modules[__name__] print(this_module) print(hasattr(this_module, 's1')) print(getattr(this_module, 's2')) ''' 执行结果: <module '__main__' from 'E:/YQLFC/study/day7/test00.py'> True <function s2 at 0x0000000000B4C378> '''

一种综合的用法是:判断一个对象的属性是否存在,若不存在就添加该属性。

>>> class test(): ... name="shuke" ... def run(self): ... return "HelloWord" ... >>> t=test() >>> getattr(t, "age") #age属性不存在 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> AttributeError: test instance has no attribute 'age' >>> getattr(t, "age", setattr(t, "age", "18")) #age属性不存在时,设置该属性 '18' >>> getattr(t, "age") #可检测设置成功 '18' >>>

导入其他模块时,利用反射查找该模块是否存在某个方法

#!/usr/bin/env python # -*- coding:utf-8 -*- def test(): print('from the test')

#!/usr/bin/env python # -*- coding:utf-8 -*- """ 程序目录: module_test.py index.py 当前文件: index.py """ import module_test as obj #obj.test() print(hasattr(obj,'test')) getattr(obj,'test')()

2.3 反射的优点

优点:

- 实现可插拔机制

- 动态导入模块(基于反射当前模块成员)

有俩程序员,一个lucy,一个是shuke,lili在写程序的时候需要用到shuke所写的类,但是shuke去跟女朋友度蜜月去了,还没有完成他写的类,lili想到了反射,使用了反射机制lili可以继续完成自己的代码,等shuke度蜜月回来后再继续完成类的定义并且去实现lili想要的功能。

class FtpClient: 'ftp客户端,但是还么有实现具体的功能' def __init__(self,addr): print('正在连接服务器[%s]' %addr) self.addr=addr

#from module import FtpClient f1=FtpClient('192.168.1.1') if hasattr(f1,'get'): func_get=getattr(f1,'get') func_get() else: print('---->不存在此方法') print('处理其他的逻辑')

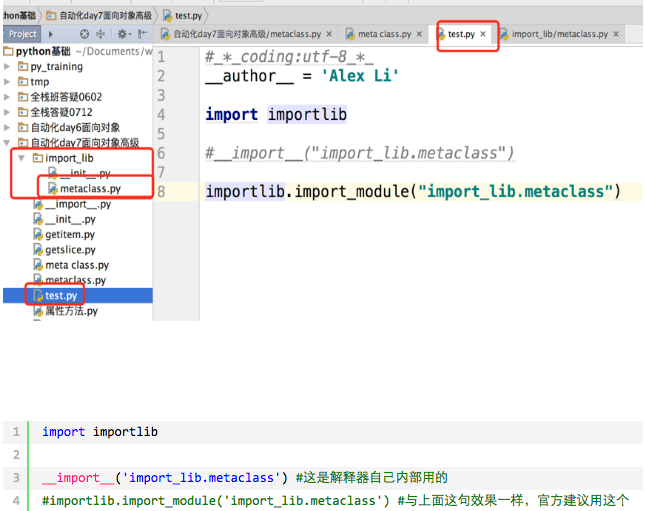

动态导入模块

三. __setattr__,__delattr__,__getattr__

三者的区别:

- `__getattr`从对象中读取某个属性时,首先需要从self.__dicts__中搜索该属性,再从__getattr__中查找。

- `__setattr__`函数是用来设置对象的属性,通过object中的__setattr__函数来设置属性。

- `__delattr__`函数式用来删除对象的属性。

class Foo: x=1 def __init__(self,y): self.y=y def __getattr__(self, item): print('----> from getattr:你找的属性不存在') def __setattr__(self, key, value): print('----> from setattr') # self.key=value # 这就无限递归了,每次的赋值操作都会调用__setattr方法 self.__dict__[key]=value # 应该使用这种方式在类的实例化后的对象字典中真正的去设置值 def __delattr__(self, item): print('----> from delattr') # del self.item # 无限递归了,每次的del操作都会调用__delattr方法 self.__dict__.pop(item) # __setattr__添加/修改属性会触发它的执行 f1=Foo(100) print(f1.__dict__) # 因为重写了__setattr__,凡是赋值操作都会触发它的运行,你啥都没写,就是根本没赋值,除非你直接操作属性字典,否则永远无法赋值 f1.a=30 print(f1.__dict__) # __delattr__删除属性的时候会触发 f1.__dict__['a']=10 # 我们可以直接修改属性字典,来完成添加/修改属性的操作 del f1.a print(f1.__dict__) # __getattr__只有在使用时调用属性且属性不存在的时候才会触发 f1.name """ 执行结果: ----> from setattr {'y': 100} ----> from setattr {'a': 30, 'y': 100} ----> from delattr {'y': 100} ----> from getattr:你找的属性不存在 """

四. 二次加工标准类型(包装)

包装: python为大家提供了标准数据类型,以及丰富的内置方法,其实在很多场景下我们都需要基于标准数据类型来定制我们自己的数据类型,新增/改写方法,这就用到了我们刚学的继承/派生知识(其他的标准类型均可以通过下面的方式进行二次加工)

二次加工标准类型:类(list),clear方法加权限控制。

# 继承列表所有的属性,重写append和clear方法 class List(list): # 继承list所有的属性,也可以派生出自己新的,比如append和mid def __init__(self,item,tag=False): # tag用于权限控制 super().__init__(item) self.tag=tag def append(self, p_object): # print(p_object) if not isinstance(p_object,str): # 类型判断逻辑处理,必须为字符串类型 raise TypeError('%s must be str' % p_object) super(List,self).append(p_object) @property def mid(self): # 取列表的中间值 mid_index=len(self)//2 return self[mid_index] def clear(self): # 清空列表必须有权限 if not self.tag: raise PermissionError('not permissive') super().clear() self.tag=False # 重置tag默认值 l=List([1,2,3,4,5]) l.append('Hello') l.append('World') l.append('shuke') print(l) print(l.mid) l.insert(0,'Python') print(l) """ 执行结果: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 'Hello', 'World', 'shuke'] 5 ['Python', 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 'Hello', 'World', 'shuke'] """ # l.tag=True # 修改tag属性后,清空列表成功 l.clear() print(l) """ 执行结果: Traceback (most recent call last): File "E:/YQLFC/study/day8/二次加工标准类型.py", line 52, in <module> l.clear() File "E:/YQLFC/study/day8/二次加工标准类型.py", line 31, in clear raise PermissionError('not permissive') PermissionError: not permissive """

授权: 授权是包装的一个特性, 包装一个类型通常是对已存在的类型的一些定制,这种做法可以新建,修改或删除原有产品的功能。其它的则保持原样。授权的过程,即是所有更新的功能都是由新类的某部分来处理,但已存在的功能就授权给对象的默认属性。

实现授权的关键点就是覆盖__getattr__方法。

#授权 import time class Open: def __init__(self,filepath,mode='r',encoding='utf-8'): self.filepath=filepath self.mode=mode self.encoding=encoding self.f=open(self.filepath,mode=self.mode,encoding=self.encoding) # 真实的open函数对象 def write(self,msg): t=time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %X') self.f.write('%s %s\n' %(t,msg)) # 使用open函数对象self.f来调用write方法写入文件 def __getattr__(self, item): # 使用点调用属性且属性不存在的时候会触发__getattr方法 # print(item,type(item)) return getattr(self.f,item) obj=Open('a.txt','w+',encoding='utf-8') # obj.f.write('11111\n') # 和下面方法效果一样,为了完全模拟open函数功能 # obj.f.write('2222\n') # obj.f.write('33233\n') # obj.f.close() obj.write('您好!\n') obj.write('北京欢迎你!\n') obj.write('再见!\n') obj.seek(0) print(obj.read()) # 相当于self.f.read() obj.close() # 相当于self.f.close()

#!/usr/bin/python # -*- coding:utf-8 -*- # 我们来加上b模式支持 import time class FileHandle: def __init__(self,filename,mode='r',encoding='utf-8'): if 'b' in mode: self.file=open(filename,mode) else: self.file=open(filename,mode,encoding=encoding) self.filename=filename self.mode=mode self.encoding=encoding def write(self,line): if 'b' in self.mode: if not isinstance(line,bytes): raise TypeError('must be bytes') self.file.write(line) def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.file,item) def __str__(self): if 'b' in self.mode: res="<_io.BufferedReader name='%s'>" %self.filename else: res="<_io.TextIOWrapper name='%s' mode='%s' encoding='%s'>" %(self.filename,self.mode,self.encoding) return res f1=FileHandle('b.txt','wb') # f1.write('Hello') #自定制的write,不用在进行encode转成二进制去写了,简单,大气 f1.write('你好啊'.encode('utf-8')) print(f1) f1.close()

#练习一 class List: def __init__(self,seq): self.seq=seq def append(self, p_object): ' 派生自己的append加上类型检查,覆盖原有的append' if not isinstance(p_object,int): raise TypeError('must be int') self.seq.append(p_object) @property def mid(self): '新增自己的方法' index=len(self.seq)//2 return self.seq[index] def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.seq,item) def __str__(self): return str(self.seq) l=List([1,2,3]) print(l) l.append(4) print(l) # l.append('3333333') #报错,必须为int类型 print(l.mid) #基于授权,获得insert方法 l.insert(0,-123) print(l) #练习二 class List: def __init__(self,seq,permission=False): self.seq=seq self.permission=permission def clear(self): if not self.permission: raise PermissionError('not allow the operation') self.seq.clear() def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.seq,item) def __str__(self): return str(self.seq) l=List([1,2,3]) # l.clear() #此时没有权限,抛出异常 l.permission=True print(l) l.clear() print(l) #基于授权,获得insert方法 l.insert(0,-123) print(l)

五 __getattribute__

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattr__(self, item): print('执行的是我') # return self.__dict__[item] f1=Foo(10) print(f1.x) f1.xxxxxx #不存在的属性访问,触发__getattr__

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattribute__(self, item): print('不管是否存在,我都会执行') f1=Foo(10) f1.x f1.xxxxxx

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattr__(self, item): print('执行的是我') # return self.__dict__[item] def __getattribute__(self, item): print('不管是否存在,我都会执行') raise AttributeError('哈哈') f1=Foo(10) f1.x f1.xxxxxx #当__getattribute__与__getattr__同时存在,只会执行__getattrbute__,除非__getattribute__在执行过程中抛出异常AttributeError

六 描述符(__get__,__set__,__delete__)

6.1 描述符是什么?

描述符本质就是一个新式类,在这个新式类中,至少实现了__get__(),__set__(),__delete__()中的一个,这也被称为描述符协议。

__get__():调用一个属性时,触发

__set__():为一个属性赋值时,触发

__delete__():采用del删除属性时,触发

class Foo: #在python3中Foo是新式类,它实现了三种方法,这个类就被称作一个描述符 def __get__(self, instance, owner): pass def __set__(self, instance, value): pass def __delete__(self, instance): pass

6.2 描述符的作用?

描述符的作用是用来代理另外一个类的属性的(必须把描述符定义成这个类的类属性,不能定义到构造函数中)

class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('触发get') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('触发set') def __delete__(self, instance): print('触发delete') #包含这三个方法的新式类称为描述符,由这个类产生的实例进行属性的调用/赋值/删除,并不会触发这三个方法 f1=Foo() f1.name='egon' f1.name del f1.name #疑问:何时,何地,会触发这三个方法的执行

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') #描述符Int class Int: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Int调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Int设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Int删除...') class People: name=Str() age=Int() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age #何地?:定义成另外一个类的类属性 #何时?:且看下列演示 p1=People('alex',18) #描述符Str的使用 p1.name p1.name='egon' del p1.name #描述符Int的使用 p1.age p1.age=18 del p1.age #我们来瞅瞅到底发生了什么 print(p1.__dict__) print(People.__dict__) #补充 print(type(p1) == People) #type(obj)其实是查看obj是由哪个类实例化来的 print(type(p1).__dict__ == People.__dict__)

6.3 描述符分类

数据描述符:至少实现了__get__()和__set__()

class Foo: def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set') def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get')

非数据描述符:没有实现__set__()

class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get')

6.4 注意事项

- 描述符本身应该定义成新式类,被代理的类也应该是新式类

- 必须把描述符定义成这个类的类属性,不能为定义到构造函数中

- 要严格遵循该优先级,优先级由高到底分别是

1.类属性

2.数据描述符

3.实例属性

4.非数据描述符

5.找不到的属性触发__getattr__()

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') class People: name=Str() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age p1=People('egon',18) #如果描述符是一个数据描述符(即有__get__又有__set__),那么p1.name的调用与赋值都是触发描述符的操作,于p1本身无关了,相当于覆盖了实例的属性 p1.name='egonnnnnn' p1.name print(p1.__dict__)#实例的属性字典中没有name,因为name是一个数据描述符,优先级高于实例属性,查看/赋值/删除都是跟描述符有关,与实例无关了 del p1.name

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') class People: name=Str() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age #基于上面的演示,我们已经知道,在一个类中定义描述符它就是一个类属性,存在于类的属性字典中,而不是实例的属性字典 #那既然描述符被定义成了一个类属性,直接通过类名也一定可以调用吧,没错 People.name #恩,调用类属性name,本质就是在调用描述符Str,触发了__get__() People.name='egon' #那赋值呢,我去,并没有触发__set__() del People.name #赶紧试试del,我去,也没有触发__delete__() #结论:描述符对类没有作用-------->傻逼到家的结论 ''' 原因:描述符在使用时被定义成另外一个类的类属性,因而类属性比二次加工的描述符伪装而来的类属性有更高的优先级 People.name #恩,调用类属性name,找不到就去找描述符伪装的类属性name,触发了__get__() People.name='egon' #那赋值呢,直接赋值了一个类属性,它拥有更高的优先级,相当于覆盖了描述符,肯定不会触发描述符的__set__() del People.name #同上 '''

class Foo: def func(self): print('我胡汉三又回来了') f1=Foo() f1.func() #调用类的方法,也可以说是调用非数据描述符 #函数是一个非数据描述符对象(一切皆对象么) print(dir(Foo.func)) print(hasattr(Foo.func,'__set__')) print(hasattr(Foo.func,'__get__')) print(hasattr(Foo.func,'__delete__')) #有人可能会问,描述符不都是类么,函数怎么算也应该是一个对象啊,怎么就是描述符了 #笨蛋哥,描述符是类没问题,描述符在应用的时候不都是实例化成一个类属性么 #函数就是一个由非描述符类实例化得到的对象 #没错,字符串也一样 f1.func='这是实例属性啊' print(f1.func) del f1.func #删掉了非数据 f1.func()

class Foo: def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set') def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') class Room: name=Foo() def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length #name是一个数据描述符,因为name=Foo()而Foo实现了get和set方法,因而比实例属性有更高的优先级 #对实例的属性操作,触发的都是描述符的 r1=Room('厕所',1,1) r1.name r1.name='厨房' class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') class Room: name=Foo() def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length #name是一个非数据描述符,因为name=Foo()而Foo没有实现set方法,因而比实例属性有更低的优先级 #对实例的属性操作,触发的都是实例自己的 r1=Room('厕所',1,1) r1.name r1.name='厨房'

class Foo: def func(self): print('我胡汉三又回来了') def __getattr__(self, item): print('找不到了当然是来找我啦',item) f1=Foo() f1.xxxxxxxxxxx

6.5 描述符的使用

众所周知,python是弱类型语言,即参数的赋值没有类型限制,下面我们通过描述符机制来实现类型限制功能

class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('egon',18,3231.3) #调用 print(p1.__dict__) p1.name #赋值 print(p1.__dict__) p1.name='egonlin' print(p1.__dict__) #删除 print(p1.__dict__) del p1.name print(p1.__dict__)

class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary #疑问:如果我用类名去操作属性呢 People.name #报错,错误的根源在于类去操作属性时,会把None传给instance #修订__get__方法 class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary print(People.name) #完美,解决

class Str: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): #如果不是期望的类型,则抛出异常 raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name',str) #新增类型限制str def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People(123,18,3333.3)#传入的name因不是字符串类型而抛出异常

class Typed: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Typed('name',str) age=Typed('name',int) salary=Typed('name',float) def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People(123,18,3333.3) p1=People('shuke','18',3333.3) p1=People('shuke',18,3333)

大刀阔斧之后我们已然能实现功能了,但是问题是,如果我们的类有很多属性,你仍然采用在定义一堆类属性的方式去实现,low,这时候我需要教你一招:独孤九剑

def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>') return cls @decorate #无参:People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('shuke',18,3333.3)

终极大招

class Typed: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) def typeassert(**kwargs): def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>',kwargs) for name,expected_type in kwargs.items(): setattr(cls,name,Typed(name,expected_type)) return cls return decorate @typeassert(name=str,age=int,salary=float) #有参:1.运行typeassert(...)返回结果是decorate,此时参数都传给kwargs 2.People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary print(People.__dict__) p1=People('shuke',18,3333.3)

6.6 总结

描述符是可以实现大部分python类特性中的底层魔法,包括@classmethod,@staticmethd,@property甚至是__slots__属性。

描述父是很多高级库和框架的重要工具之一,描述符通常是使用到装饰器或者元类的大型框架中的一个组件。

6.7 应用示例

利用描述符原理完成一个自定制@property,实现延迟计算(本质就是把一个函数属性利用装饰器原理做成一个描述符:类的属性字典中函数名为key,value为描述符类产生的对象)

class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @property def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area)

class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('这是我们自己定制的静态属性,r1.area实际是要执行r1.area()') if instance is None: return self return self.func(instance) #此时你应该明白,到底是谁在为你做自动传递self的事情 class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @Lazyproperty #area=Lazyproperty(area) 相当于定义了一个类属性,即描述符 def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area)

class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('这是我们自己定制的静态属性,r1.area实际是要执行r1.area()') if instance is None: return self else: print('--->') value=self.func(instance) setattr(instance,self.func.__name__,value) #计算一次就缓存到实例的属性字典中 return value class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @Lazyproperty #area=Lazyproperty(area) 相当于'定义了一个类属性,即描述符' def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area) #先从自己的属性字典找,没有再去类的中找,然后出发了area的__get__方法 print(r1.area) #先从自己的属性字典找,找到了,是上次计算的结果,这样就不用每执行一次都去计算

#缓存不起来了 class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('这是我们自己定制的静态属性,r1.area实际是要执行r1.area()') if instance is None: return self else: value=self.func(instance) instance.__dict__[self.func.__name__]=value return value # return self.func(instance) #此时你应该明白,到底是谁在为你做自动传递self的事情 def __set__(self, instance, value): print('hahahahahah') class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @Lazyproperty #area=Lazyproperty(area) 相当于定义了一个类属性,即描述符 def area(self): return self.width * self.length print(Room.__dict__) r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area) print(r1.area) print(r1.area) print(r1.area) #缓存功能失效,每次都去找描述符了,为何,因为描述符实现了set方法,它由非数据描述符变成了数据描述符,数据描述符比实例属性有更高的优先级,因而所有的属性操作都去找描述符了

6.8 定制@classmethod

class ClassMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(owner) return feedback class People: name='linhaifeng' @ClassMethod # say_hi=ClassMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(cls): print('你好啊,帅哥 %s' %cls.name) People.say_hi() p1=People() p1.say_hi() #疑问,类方法如果有参数呢,好说,好说 class ClassMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(*args,**kwargs): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(owner,*args,**kwargs) return feedback class People: name='linhaifeng' @ClassMethod # say_hi=ClassMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(cls,msg): print('你好啊,帅哥 %s %s' %(cls.name,msg)) People.say_hi('你是那偷心的贼') p1=People() p1.say_hi('你是那偷心的贼')

6.9 定制@staticmethod

class StaticMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(*args,**kwargs): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(*args,**kwargs) return feedback class People: @StaticMethod# say_hi=StaticMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(x,y,z): print('------>',x,y,z) People.say_hi(1,2,3) p1=People() p1.say_hi(4,5,6)

六 再看property

一个静态属性property本质就是实现了get,set,delete三种方法

class Foo: @property def AAA(self): print('get的时候运行我啊') @AAA.setter def AAA(self,value): print('set的时候运行我啊') @AAA.deleter def AAA(self): print('delete的时候运行我啊') #只有在属性AAA定义property后才能定义AAA.setter,AAA.deleter f1=Foo() f1.AAA f1.AAA='aaa' del f1.AAA

class Foo: def get_AAA(self): print('get的时候运行我啊') def set_AAA(self,value): print('set的时候运行我啊') def delete_AAA(self): print('delete的时候运行我啊') AAA=property(get_AAA,set_AAA,delete_AAA) #内置property三个参数与get,set,delete一一对应 f1=Foo() f1.AAA f1.AAA='aaa' del f1.AAA

如何使用?

class Goods: def __init__(self): # 原价 self.original_price = 100 # 折扣 self.discount = 0.8 @property def price(self): # 实际价格 = 原价 * 折扣 new_price = self.original_price * self.discount return new_price @price.setter def price(self, value): self.original_price = value @price.deleter def price(self): del self.original_price obj = Goods() obj.price # 获取商品价格 obj.price = 200 # 修改商品原价 print(obj.price) del obj.price # 删除商品原价

#实现类型检测功能 #第一关: class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name @property def name(self): return self.name # p1=People('alex') #property自动实现了set和get方法属于数据描述符,比实例属性优先级高,所以你这面写会触发property内置的set,抛出异常 #第二关:修订版 class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #实例化就触发property @property def name(self): # return self.name #无限递归 print('get------>') return self.DouNiWan @name.setter def name(self,value): print('set------>') self.DouNiWan=value @name.deleter def name(self): print('delete------>') del self.DouNiWan p1=People('alex') #self.name实际是存放到self.DouNiWan里 print(p1.name) print(p1.name) print(p1.name) print(p1.__dict__) p1.name='egon' print(p1.__dict__) del p1.name print(p1.__dict__) #第三关:加上类型检查 class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #实例化就触发property @property def name(self): # return self.name #无限递归 print('get------>') return self.DouNiWan @name.setter def name(self,value): print('set------>') if not isinstance(value,str): raise TypeError('必须是字符串类型') self.DouNiWan=value @name.deleter def name(self): print('delete------>') del self.DouNiWan p1=People('shuke') #self.name实际是存放到self.DouNiWan里 p1.name=1

七. __setitem__,__getitem,__delitem__

像操作字典的方式一样操作对象的属性

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __getitem__(self, item): print(self.__dict__[item]) def __setitem__(self, key, value): self.__dict__[key]=value def __delitem__(self, key): print('del obj[key]时,我执行') self.__dict__.pop(key) def __delattr__(self, item): print('del obj.key时,我执行') self.__dict__.pop(item) f1=Foo('sb') f1['age']=18 f1['age1']=19 del f1.age1 del f1['age'] f1['name']='shuke' print(f1.__dict__) """ 执行结果: del obj.key时,我执行 del obj[key]时,我执行 {'name': 'shuke'} """

八. __str__,__repr__,__format__

改变对象的字符串显示__str__,__repr__

自定制格式化字符串__format__

-

__str__,__repr__

我们先定义一个Student类,打印一个实例:

>>> class Student(object): ... def __init__(self, name): ... self.name = name ... >>> print(Student('Michael')) <__main__.Student object at 0x109afb190> # 类的内存地址

打印出一堆<__main__.Student object at 0x109afb190>,不好看。

怎么才能打印得好看呢?只需要定义好__str__()方法,返回一个好看的字符串就可以了:

>>> class Student(object): ... def __init__(self, name): ... self.name = name ... def __str__(self): ... return 'Student object (name: %s)' % self.name ... >>> print(Student('Michael')) # 会触发__str__方法执行 Student object (name: Michael)

这样打印出来的实例,不但好看,而且容易看出实例内部重要的数据。

但是细心的朋友会发现直接敲变量不用print,打印出来的实例还是不好看:

>>> s = Student('Michael') >>> s <__main__.Student object at 0x109afb310>

这是因为直接显示变量调用的不是__str__(),而是__repr__(),两者的区别是__str__()返回用户看到的字符串,而__repr__()返回程序开发者看到的字符串,也就是说,__repr__()是为调试服务的。

解决办法是再定义一个__repr__()。但是通常__str__()和__repr__()代码都是一样的,所以,有个偷懒的写法:

class Student(object): def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def __str__(self): return 'Student object (name=%s)' % self.name __repr__ = __str__

自定制格式化字符串__format__

format_dict={ 'nat':'{obj.name}-{obj.addr}-{obj.type}',#学校名-学校地址-学校类型 'tna':'{obj.type}:{obj.name}:{obj.addr}',#学校类型:学校名:学校地址 'tan':'{obj.type}/{obj.addr}/{obj.name}',#学校类型/学校地址/学校名 } class School: def __init__(self,name,addr,type): self.name=name self.addr=addr self.type=type def __repr__(self): return 'School(%s,%s)' %(self.name,self.addr) def __str__(self): return '(%s,%s)' %(self.name,self.addr) def __format__(self, format_spec): # if format_spec if not format_spec or format_spec not in format_dict: format_spec='nat' fmt=format_dict[format_spec] return fmt.format(obj=self) s1=School('oldboy1','北京','私立') print('from repr: ',repr(s1)) print('from str: ',str(s1)) print(s1) ''' str函数或者print函数--->obj.__str__() repr或者交互式解释器--->obj.__repr__() 如果__str__没有被定义,那么就会使用__repr__来代替输出 注意:这俩方法的返回值必须是字符串,否则抛出异常 ''' print(format(s1,'nat')) print(format(s1,'tna')) print(format(s1,'tan')) print(format(s1,'asfdasdffd')) """ 执行结果: from repr: School(oldboy1,北京) from str: (oldboy1,北京) (oldboy1,北京) oldboy1-北京-私立 私立:oldboy1:北京 私立/北京/oldboy1 oldboy1-北京-私立 """

date_dic={ 'ymd':'{0.year}:{0.month}:{0.day}', 'dmy':'{0.day}/{0.month}/{0.year}', 'mdy':'{0.month}-{0.day}-{0.year}', } class Date: def __init__(self,year,month,day): self.year=year self.month=month self.day=day def __format__(self, format_spec): if not format_spec or format_spec not in date_dic: format_spec='ymd' fmt=date_dic[format_spec] return fmt.format(self) d1=Date(2016,12,29) print(format(d1)) print('{:mdy}'.format(d1))

class A: pass class B(A): pass print(issubclass(B,A)) #B是A的子类,返回True a1=A() print(isinstance(a1,A)) #a1是A的实例

九. __next__和__iter__实现迭代器协议

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): n=self.x self.x+=1 return self.x f=Foo(3) for i in f: print(i)

class Foo: def __init__(self,n,stop): self.n=n self.stop=stop def __next__(self): if self.n >= self.stop: raise StopIteration x=self.n self.n+=1 return x def __iter__(self): return self obj=Foo(0,5) # 0 1 2 3 4 print(next(obj)) # obj.__next__() print(next(obj)) # obj.__next__() from collections import Iterator print(isinstance(obj,Iterator)) """ 执行结果: 0 1 True """

class Range: def __init__(self,n,stop,step): self.n=n self.stop=stop self.step=step def __next__(self): if self.n >= self.stop: raise StopIteration x=self.n self.n+=self.step return x def __iter__(self): return self for i in Range(1,7,3): # print(i)

class Fib: def __init__(self): self._a=0 self._b=1 def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): self._a,self._b=self._b,self._a + self._b return self._a f1=Fib() print(f1.__next__()) print(next(f1)) print(next(f1)) for i in f1: if i > 100: break print('%s ' %i,end='')

十. __doc__

class Foo: '我是描述信息' pass print(Foo.__doc__)

该属性无法继承给子类

class Foo: '我是描述信息' pass class Bar(Foo): pass print(Bar.__doc__) #该属性无法继承给子类

十一. __module__和__class__

__module__ 表示当前操作的对象在那个模块

__class__ 表示当前操作的对象的类是什么

#!/usr/bin/env python # -*- coding:utf-8 -*- class C: def __init__(self): self.name = 'jack'

from lib.aa import C obj = C() print obj.__module__ # 输出 lib.aa,即:输出模块 print obj.__class__ # 输出 lib.aa.C,即:输出类

十二. __del__

析构方法,当对象在内存中被释放时,自动触发执行。

注: 此方法一般无须定义,因为Python是一门高级语言,程序员在使用时无需关心内存的分配和释放,因为此工作都是交给Python解释器来执行,所以,析构函数的调用是由解释器在进行垃圾回收时自动触发执行的。

class Foo: def __del__(self): print('执行我啦') f1=Foo() del f1 print('------->') #输出结果 执行我啦 ------->

class Foo: def __del__(self): print('执行我啦') f1=Foo() # del f1 print('------->') #输出结果 -------> 执行我啦

十三. __enter__和__exit__

我们知道在操作文件对象的时候可以这么写

with open('a.txt') as f: '代码块'

上述叫做上下文管理协议,即with语句,为了让一个对象兼容with语句,必须在这个对象的类中声明__enter__和__exit__方法

class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') # return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') # print(f,f.name)

__exit__()中的三个参数分别代表异常类型,异常值和追溯信息,with语句中代码块出现异常,则with后的代码都无法执行

class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') raise AttributeError('***着火啦,救火啊***') print('0'*100) #------------------------------->不会执行

如果__exit()返回值为True,那么异常会被清空,就好像啥都没发生一样,with后的语句正常执行

class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) return True with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') raise AttributeError('***着火啦,救火啊***') print('0'*100) #------------------------------->会执行

class Open: def __init__(self,filepath,mode='r',encoding='utf-8'): self.filepath=filepath self.mode=mode self.encoding=encoding def __enter__(self): # print('enter') self.f=open(self.filepath,mode=self.mode,encoding=self.encoding) return self.f def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): # print('exit') self.f.close() return True def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.f,item) with Open('a.txt','w') as f: print(f) f.write('aaaaaa') f.wasdf #抛出异常,交给__exit__处理

用途或者说好处:

1.使用with语句的目的就是把代码块放入with中执行,with结束后,自动完成清理工作,无须手动干预

2.在需要管理一些资源比如文件,网络连接和锁的编程环境中,可以在__exit__中定制自动释放资源的机制,你无须再去关系这个问题,这将大有用处

十四. __call__

对象后面加括号,触发执行。

注: 构造方法的执行是由创建对象触发的,即:对象 = 类名() ;而对于 __call__ 方法的执行是由对象后加括号触发的,即:对象() 或者 类()()

class Foo: def __init__(self): pass def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') obj = Foo() # 执行 __init__ obj() # 执行 __call__

十五. eval(),exec()

1、eval()

函数的作用: 计算指定表达式的值。也就是说它要执行的Python代码只能是单个运算表达式(注意eval不支持任意形式的赋值操作),而不能是复杂的代码逻辑,这一点和lambda表达式比较相似。

函数语法格式:

eval(expression, globals=None, locals=None)

- 参数说明:

- expression:必选参数,可以是字符串,也可以是一个任意的code对象实例(可以通过compile函数创建)。如果它是一个字符串,它会被当作一个(使用globals和locals参数作为全局和本地命名空间的)Python表达式进行分析和解释。

- globals:可选参数,表示全局命名空间(存放全局变量),如果被提供,则必须是一个字典对象。

- locals:可选参数,表示当前局部命名空间(存放局部变量),如果被提供,可以是任何映射对象。如果该参数被忽略,那么它将会取与globals相同的值。

- 如果globals与locals都被忽略,那么它们将取eval()函数被调用环境下的全局命名空间和局部命名空间。

- 返回值:

- 如果expression是一个code对象,且创建该code对象时,compile函数的mode参数是'exec',那么eval()函数的返回值是None;

- 否则,如果expression是一个输出语句,如print(),则eval()返回结果为None;

- 否则,expression表达式的结果就是eval()函数的返回值;

x = 10 def func(): y = 20 a = eval('x + y') print('a: ', a) b = eval('x + y', {'x': 1, 'y': 2}) print('b: ', b) c = eval('x + y', {'x': 1, 'y': 2}, {'y': 3, 'z': 4}) print('c: ', c) d = eval('print(x, y)') print('d: ', d) func() """ 执行结果: a: 30 b: 3 c: 4 10 20 d: None """

- 对输出结果的解释:

- 对于变量a,eval函数的globals和locals参数都被忽略了,因此变量x和变量y都取得的是eval函数被调用环境下的作用域中的变量值,即:x = 10, y = 20,a = x + y = 30

- 对于变量b,eval函数只提供了globals参数而忽略了locals参数,因此locals会取globals参数的值,即:x = 1, y = 2,b = x + y = 3

- 对于变量c,eval函数的globals参数和locals都被提供了,那么eval函数会先从全部作用域globals中找到变量x, 从局部作用域locals中找到变量y,即:x = 1, y = 3, c = x + y = 4

- 对于变量d,因为print()函数不是一个计算表达式,没有计算结果,因此返回值为None

2.exec()

函数的作用: 动态执行Python代码。也就是说exec可以执行复杂的Python代码,而不像eval函数那么样只能计算一个表达式的值。

函数语法格式:

exec(object[, globals[, locals]])

- 参数说明:

-

exec:三个参数

参数一:字符串形式的命令,object:必选参数,表示需要被指定的Python代码。它必须是字符串或code对象。如果object是一个字符串,该字符串会先被解析为一组Python语句,然后在执行(除非发生语法错误)。如果object是一个code对象,那么它只是被简单的执行。

-

参数二:全局作用域,globals:可选参数,同eval函数

-

参数三:局部作用域,locals:可选参数,同eval函数

-

exec会在指定的局部作用域内执行字符串内的代码,除非明确地使用global关键字

- 返回值:exec函数的返回值永远为None.

需要说明的是在Python 2中exec不是函数,而是一个内置语句(statement),但是Python 2中有一个execfile()函数。可以理解为Python 3把exec这个statement和execfile()函数的功能够整合到一个新的exec()函数中去了:

- eval()函数与exec()函数的区别:

- eval()函数只能计算单个表达式的值,而exec()函数可以动态运行代码段。

- eval()函数可以有返回值,而exec()函数返回值永远为None。

x = 10 def func(): y = 20 a = exec('x + y') print('a: ', a) b = exec('x + y', {'x': 1, 'y': 2}) print('b: ', b) c = exec('x + y', {'x': 1, 'y': 2}, {'y': 3, 'z': 4}) print('c: ', c) d = exec('print(x, y)') print('d: ', d) func() """ 执行结果: a: None b: None c: None 10 20 d: None """

x = 10 expr = """ z = 30 sum = x + y + z print(sum) """ def func(): y = 20 exec(expr) exec(expr, {'x': 1, 'y': 2}) exec(expr, {'x': 1, 'y': 2}, {'y': 3, 'z': 4}) func() """ 执行结果: 60 33 34 """

对输出结果的解释:

前两个输出跟上面解释的eval函数执行过程一样,不做过多解释。关于最后一个数字34,我们可以看出是:x = 1, y = 3是没有疑问的。关于z为什么还是30而不是4,这其实也很简单,我们只需要在理一下代码执行过程就可以了,其执行过程相当于:

x = 1 y = 2 def func(): y = 3 z = 4 z = 30 sum = x + y + z print(sum) func()

十六. 元类(metaclass)

1. 引子(类也是对象)

class Foo: pass f1=Foo() #f1是通过Foo类实例化的对象

python中一切皆是对象,类本身也是一个对象,当使用关键字class的时候,python解释器在加载class的时候就会创建一个对象(这里的对象指的是类而非类的实例),因而我们可以将类当作一个对象去使用,同样满足第一类对象的概念,可以:

-

把类赋值给一个变量

-

把类作为函数参数进行传递

-

把类作为函数的返回值

-

在运行时动态地创建类

上例可以看出f1是由Foo这个类产生的对象,而Foo本身也是对象,那它又是由哪个类产生的呢?

# type函数可以查看类型,也可以用来查看对象的类,二者是一样的 print(type(f1)) # 输出:<class '__main__.Foo'> 表示,obj 对象由Foo类创建 print(type(Foo)) # 输出:<type 'type'>

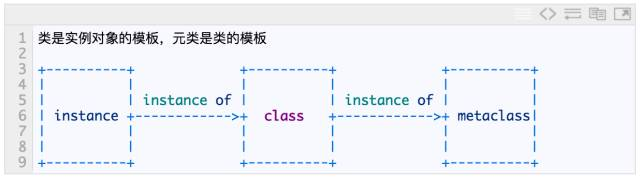

2.元类的定义

元类是类的类,是类的模板

元类是用来控制如何创建类的,正如类是创建对象的模板一样,而元类的主要目的是为了控制类的创建行为。

元类的实例化的结果为我们用class定义的类,正如类的实例为对象(f1对象是Foo类的一个实例,Foo类是 type 类的一个实例)

type是python的一个内建元类,用来直接控制生成类,python中任何class定义的类其实都是type类实例化的对象。

3. 创建类的两种方式

方式一:使用class关键字

class Chinese(object): country='China' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def talk(self): print('%s is talking' %self.name)

方式二: 手动模拟class创建类的过程,将创建类的步骤拆分开,手动去创建

创建类主要分为三部分:

1 类名

2 类的父类

3 类体

#类名 class_name='Chinese' #类的父类 class_bases=(object,) #类体 class_body=""" country='China' def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def talk(self): print('%s is talking' %self.name) """

步骤一:(先处理类体->名称空间):类体定义的名字都会存放于类的名称空间中(一个局部的名称空间),我们可以事先定义一个空字典,然后用exec去执行类体的代码(exec产生名称空间的过程与真正的class过程类似,只是后者会将__开头的属性变形),生成类的局部名称空间,即填充字典。

class_dic={} exec(class_body,globals(),class_dic) print(class_dic) #{'country': 'China', 'talk': <function talk at 0x101a560c8>, '__init__': <function __init__ at 0x101a56668>}

步骤二:调用元类type(也可以自定义)来产生类Chinense

Foo=type(class_name,class_bases,class_dic) #实例化type得到对象Foo,即我们用class定义的类Foo print(Foo) print(type(Foo)) print(isinstance(Foo,type)) ''' <class '__main__.Chinese'> <class 'type'> True '''

我们看到,type 接收三个参数:

-

第 1 个参数是字符串 ‘Foo’,表示类名

-

第 2 个参数是元组 (object, ),表示所有的父类

-

第 3 个参数是字典,这里是一个空字典,表示没有定义属性和方法

补充: 若Foo类有继承,即class Foo(Bar):.... 则等同于type('Foo',(Bar,),{})

4. 一个类没有声明自己的元类,默认他的元类就是type,除了使用元类type,用户也可以通过继承type来自定义元类

所以类实例化的流程都一样,与三个方法有关:(大前提,任何名字后加括号,都是在调用一个功能,触发一个函数的执行,得到一个返回值)

1.obj=Foo(),会调用产生Foo的类内的__call__方法,Foo()的结果即__call__的结果

2.调用__call__方法的过程中,先调用Foo.__new__,得到obj,即实例化的对象,但是还没有初始化

3.调用__call__方法的过程中,如果Foo.__new__()返回了obj,再调用Foo.__init__,将obj传入,进行初始化(否则不调用Foo.__init__)

总结:

__new__更像是其他语言中的构造函数,必须有返回值,返回值就实例化的对象

__init__只是初始化函数,必须没有返回值,仅仅只是初始化功能,并不能new创建对象

前提注意:

1. 在我们自定义的元类内,__new__方法在产生obj时用type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs),用object.__new__(cls)抛出异常:TypeError: object.__new__(Mymeta) is not safe, use type.__new__()

2. 在我们自定义的类内,__new__方法在产生obj时用object.__new__(self)

元类控制创建类:

class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self): print('__init__') def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): print('__new__') def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): pass print(Foo) ''' 打印结果: __new__ None ''' ''' 分析Foo的产生过程,即Foo=Mymeta(),会触发产生Mymeta的类内的__call__,即元类的__call__: Mymeta加括号,会触发父类的__call__,即type.__call__ 在type.__call__里会调用Foo.__new__ 而Foo.__new__内只是打印操作,没有返回值,因而Mymeta的结果为None,即Foo=None '''

class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self): print('__init__') def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): # print('__new__') obj=type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) return obj def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') Foo=Mymeta() class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): pass print(Foo) ''' 基于上述表达,我们改写了__new__,返回obj,但是抛出异常: TypeError: __init__() takes 1 positional argument but 4 were given ''' #改写 class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,name,bases,dic): print('__init__') def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): print('__new__') obj=type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) return obj def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') # Foo=Mymeta() class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): pass print(Foo)

class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,name,bases,dic): for key,value in dic.items(): if key.startswith('__'): continue if not callable(value): continue if not value.__doc__: raise TypeError('%s 必须有文档注释' %key) type.__init__(self,name,bases,dic) def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): # print('__new__') obj=type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) return obj def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): # print('__call__') pass # Foo=Mymeta() class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): def f1(self): 'from f1' pass def f2(self): pass ''' 抛出异常 TypeError: f2 必须有文档注释 '''

元类控制类创建对象

class Mymeta(type): def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('__call__') class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): pass obj=Foo() #Foo加括号,触发Mymeta的__call__...

class Mymeta(type): def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #self=<class '__main__.Foo'> #args=('egon',) #kwargs={'age':18} obj=self.__new__(self) #创建对象:Foo.__new__(Foo) self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) #初始化对象:Foo.__init__(obj,'egon',age=18) return obj #一定不要忘记return class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta): def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): return object.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) obj=Foo('egon',age=18) #触发Mymeta.__call__ print(obj.__dict__)

#单例模式,比如数据库对象,实例化时参数都一样,就没必要重复产生对象,浪费内存 class Mysql: __instance=None def __init__(self,host='127.0.0.1',port='3306'): self.host=host self.port=port @classmethod def singleton(cls,*args,**kwargs): if not cls.__instance: cls.__instance=cls(*args,**kwargs) return cls.__instance obj1=Mysql() obj2=Mysql() print(obj1 is obj2) #False obj3=Mysql.singleton() obj4=Mysql.singleton() print(obj3 is obj4) #True

#单例模式,比如数据库对象,实例化时参数都一样,就没必要重复产生对象,浪费内存 class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,name,bases,dic): #定义类Mysql时就触发 self.__instance=None super().__init__(name,bases,dic) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): #Mysql(...)时触发 if not self.__instance: self.__instance=object.__new__(self) #产生对象 self.__init__(self.__instance,*args,**kwargs) #初始化对象 #上述两步可以合成下面一步 # self.__instance=super().__call__(*args,**kwargs) return self.__instance class Mysql(metaclass=Mymeta): def __init__(self,host='127.0.0.1',port='3306'): self.host=host self.port=port obj1=Mysql() obj2=Mysql() print(obj1 is obj2)

class Mytype(type): def __init__(self,class_name,bases=None,dict=None): print("Mytype init--->") print(class_name,type(class_name)) print(bases) print(dict) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('Mytype call---->',self,args,kwargs) obj=self.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) return obj class Foo(object,metaclass=Mytype):#in python3 #__metaclass__ = MyType #in python2 x=1111111111 def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): return super().__new__(cls) # return object.__new__(cls) #同上 f1=Foo('name') print(f1.__dict__)

class Mytype(type): def __init__(self,what,bases=None,dict=None): print('mytype init') def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): obj=self.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) return obj class Foo(object,metaclass=Mytype): x=1111111111 def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): return super().__new__(cls) f1=Foo('egon') print(f1.__dict__)

class Mytype(type): def __init__(self,what,bases=None,dict=None): print(what,bases,dict) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('--->') obj=object.__new__(self) self.__init__(obj,*args,**kwargs) return obj class Room(metaclass=Mytype): def __init__(self,name): self.name=name r1=Room('alex') print(r1.__dict__)

#元类总结 class Mymeta(type): def __init__(self,name,bases,dic): print('===>Mymeta.__init__') def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): print('===>Mymeta.__new__') return type.__new__(cls,*args,**kwargs) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('aaa') obj=self.__new__(self) self.__init__(self,*args,**kwargs) return obj class Foo(object,metaclass=Mymeta): def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs): return object.__new__(cls) ''' 需要记住一点:名字加括号的本质(即,任何name()的形式),都是先找到name的爹,然后执行:爹.__call__ 而爹.__call__一般做两件事: 1.调用name.__new__方法并返回一个对象 2.进而调用name.__init__方法对儿子name进行初始化 ''' ''' class 定义Foo,并指定元类为Mymeta,这就相当于要用Mymeta创建一个新的对象Foo,于是相当于执行 Foo=Mymeta('foo',(...),{...}) 因此我们可以看到,只定义class就会有如下执行效果 ===>Mymeta.__new__ ===>Mymeta.__init__ 实际上class Foo(metaclass=Mymeta)是触发了Foo=Mymeta('Foo',(...),{...})操作, 遇到了名字加括号的形式,即Mymeta(...),于是就去找Mymeta的爹type,然后执行type.__call__(...)方法 于是触发Mymeta.__new__方法得到一个具体的对象,然后触发Mymeta.__init__方法对对象进行初始化 ''' ''' obj=Foo('egon') 的原理同上 ''' ''' 总结:元类的难点在于执行顺序很绕,其实我们只需要记住两点就可以了 1.谁后面跟括号,就从谁的爹中找__call__方法执行 type->Mymeta->Foo->obj Mymeta()触发type.__call__ Foo()触发Mymeta.__call__ obj()触发Foo.__call__ 2.__call__内按先后顺序依次调用儿子的__new__和__init__方法 '''

练习一:在元类中控制把自定义类的数据属性都变成大写

class Mymetaclass(type): def __new__(cls,name,bases,attrs): update_attrs={} for k,v in attrs.items(): if not callable(v) and not k.startswith('__'): update_attrs[k.upper()]=v else: update_attrs[k]=v return type.__new__(cls,name,bases,update_attrs) class Chinese(metaclass=Mymetaclass): country='China' tag='Legend of the Dragon' #龙的传人 def walk(self): print('%s is walking' %self.name) print(Chinese.__dict__) ''' {'__module__': '__main__', 'COUNTRY': 'China', 'TAG': 'Legend of the Dragon', 'walk': <function Chinese.walk at 0x0000000001E7B950>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'Chinese' objects>, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'Chinese' objects>, '__doc__': None} '''

练习二:在元类中控制自定义的类无需__init__方法

1.元类帮其完成创建对象,以及初始化操作;

2.要求实例化时传参必须为关键字形式,否则抛出异常TypeError: must use keyword argument for key function;

3.key作为用户自定义类产生对象的属性,且所有属性变成大写

class Mymetaclass(type): # def __new__(cls,name,bases,attrs): # update_attrs={} # for k,v in attrs.items(): # if not callable(v) and not k.startswith('__'): # update_attrs[k.upper()]=v # else: # update_attrs[k]=v # return type.__new__(cls,name,bases,update_attrs) def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): if args: raise TypeError('must use keyword argument for key function') obj = object.__new__(self) #创建对象,self为类Foo for k,v in kwargs.items(): obj.__dict__[k.upper()]=v return obj class Chinese(metaclass=Mymetaclass): country='China' tag='Legend of the Dragon' #龙的传人 def walk(self): print('%s is walking' %self.name) p=Chinese(name='egon',age=18,sex='male') print(p.__dict__)

参考资料: http://www.cnblogs.com/linhaifeng/articles/6204014.html